Dear Lunatics,

I apologize that last month’s full moon—a blue moon, no less—passed without a Dispatch. Many of you kindly reached out, asking where I had disappeared to, and your digital hands found only empty air.

The truth is that I was in too much pain to write, though even in my discomfort, I kept one squinted eye on the bedroom window, following the Sturgeon Moon’s blurry progress across a misty sky.

I was looking for a nocturnal creature—one so rare that certain photographers spend their whole careers trying to capture it.

It’s shy, preferring to dwell in the spray of waterfalls, and skittish, vanishing from view if you move just a few feet in any direction.

It’s called a moonbow.

Unless you live under a cataract in Yosemite or Cumberland Falls, your best chance of spotting a moonbow is on a night when half the sky is cloud-free and dominated by a radiant full moon, while the other half is engulfed by a rainstorm.

I never thought I would see one. What are the chances those conditions would perfectly align?

But then, last month’s blue moon arrived just as a ferocious 1-in-a-1,000-year storm was breaking rainfall records in nearby towns.

Could this be the night? I wondered.

It wasn’t.

Probably because my name is not Aaron Watson.

Watson is a photographer from Colorado who, like one of those strange people who get struck by lightning multiple times in their life, has seen several moonbows.

Last month, he was awoken at 2 a.m. by the patter of rain, and when he looked out the window, he saw not a moonbow, but a double moonbow.

In a way, I did sort of see a moonbow last month.

When you live with chronic pain, your eyes become waterfalls, the flow of tears so constant and involuntary that you eventually stop noticing. (Like a hiker at a National Park, I just make sure to stay hydrated.)

For me, when last month’s full moon streaked across my sodden visual field, it leaked prismatic colors.

Yes, I know, it would be cheating to claim I saw a real moonbow.

Just like it would be cheating to answer “1971” when asked the trivia question, “When was water first discovered on the Moon?”

The “correct” answer is 2008, the year a mass spectrometer found trace water molecules when it peered inside a moon rock.

But in 1971, when the Apollo astronaut Alan Shepard stepped out of the lunar module and looked back at the Earth, he held out his gloved hand and framed our planet between his thumb and forefinger.

“[I]t makes it look beautiful,” he later recalled, “it makes it look lonely; it makes it look fragile..”

“If somebody’d said before the flight, ‘Are you going to get carried away looking at the earth from the moon?’ I would have said, ‘No, no way.’ But yet when I first looked back at the earth, standing on the moon, I cried.”

Alan Shepard who shed the first water on the Moon

When your body is in pain, it’s only natural to wish you could board a Saturn V rocket ship and launch into the void of space, leaving your mortal coil back on Earth.

Years ago, I visited the office of a renowned psychologist to discuss this yearning for escape.

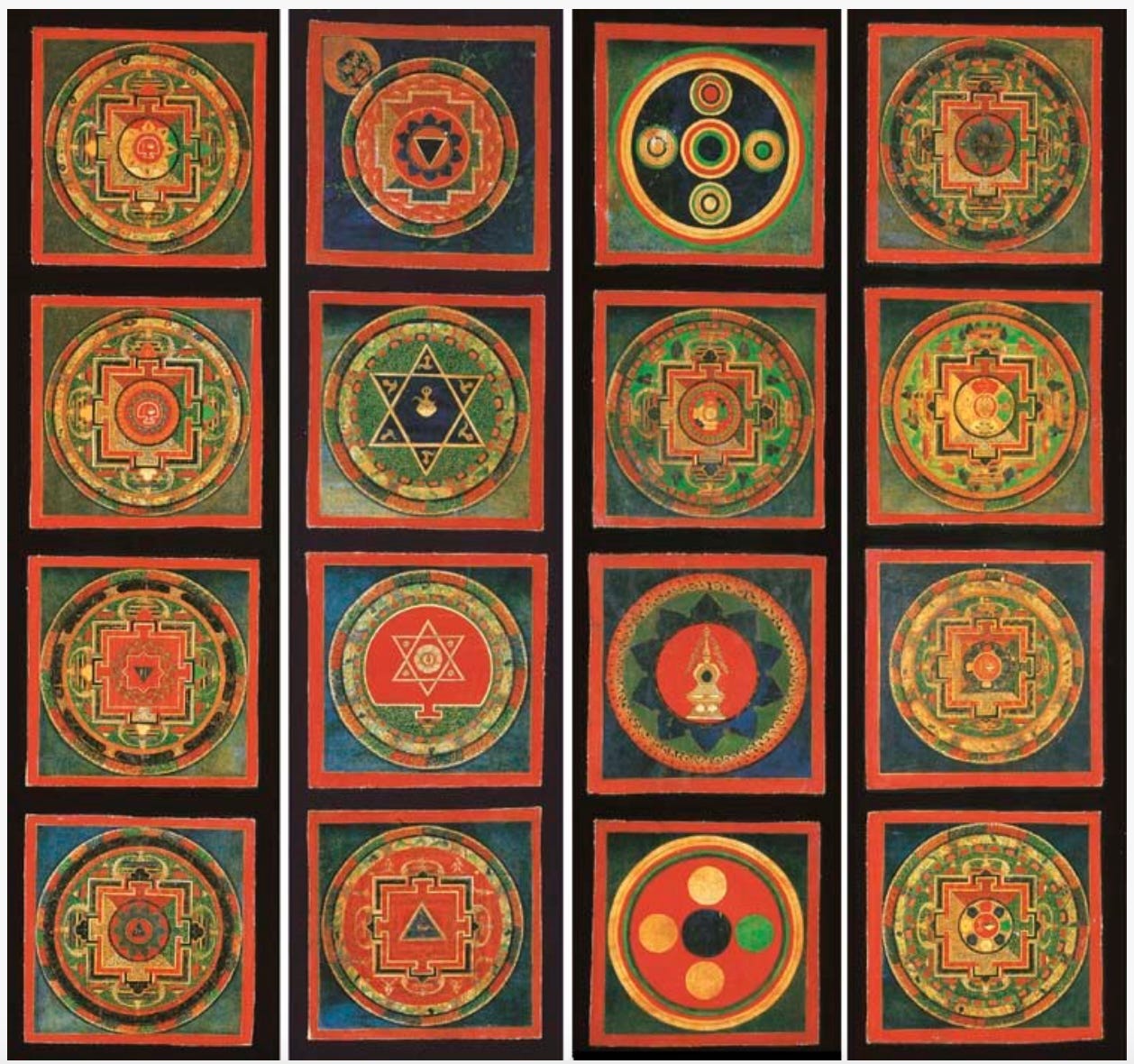

He sat at a mahogany table in front of a wall of books. I seem to remember patterned tapestries. Figurines and mandalas. But I was seeing through a sheet of rain that day.

He asked me: “When you think about leaving, do you imagine being reborn into another life?”

“No,” I answered.

“Do you imagine being reunited with a lost loved one?”

“No.”

“Do you imagine someone who’s done you wrong feeling badly?”

“No.”

“Do you imagine an end to your pain?”

“Yes.”

As he made some notes, he said, “In school, they teach us the four R’s of suicide. Rebirth, reunion, revenge, and riddance.” Without looking up, he gestured to me and said, “This is riddance.”

Recently, I’ve been thinking about Khenpo Achö, a Buddhist monk who spent his old age in a secluded cabin.

He trained himself to see his body as just another external appearance, no more solid than the reflection of the moon on the surface of a pond.

Eventually, if reports are to be believed, the monk’s body became no more solid than the moon’s watery reflection.

While the hermitage had a door and windows, the monk found he preferred to enter and exit through the walls. The groundskeepers often saw him circumambulating around the cabin, even after they had locked his door from the outside.

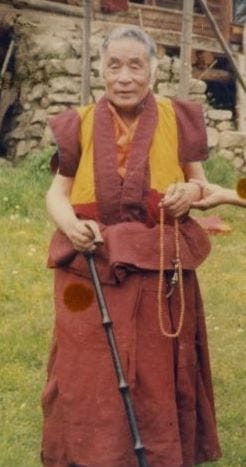

(Lest you think Khenpo Achö and the witnesses to his miraculous feats lived in some distant era, here’s a picture of the man from 1998.)

Yet Khenpo Achö’s greatest achievement came at the moment of his death.

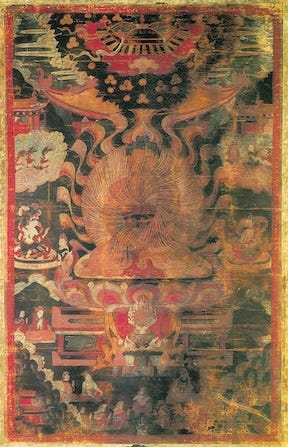

That’s when he achieved the so-called Rainbow Body.

The Rainbow Body is an exit accomplished by only the greatest of yogis. As they enter the dying process, their bodies begin to glow and emit a pleasant scent. Sometimes, a soft fragrant rain falls on the small cabin or tent or wherever they have sequestered themselves. After death, their physical body immediately begins to shrink, and when their students reach for their dying master in the darkness, they find only empty air. Over the next week, the monk’s body dissolves entirely, leaving behind hair, nails, and, blazing in the sky overhead, a pulsing rainbow.

Khenpo Achö’s posthumous rainbow burned over his cabin for days.

Instructions on how to achieve the Rainbow Body have not been known in the West until recently.

After training with Tibetan Buddhist and Bön lamas for nearly 50 years, an American meditation expert—a true Rennaisance man—received permission from lineage holders to translate the secret dying teachings into English.

The American expert, who was dying himself, raced to finish the translation, a feat that he managed, though he did not live to see the book’s ultimate publication last year.

I was saddened to hear of the American expert’s passing. I had only met the man once, but it had been a memorable conversation.

He was the renowned psychologist I had visited years ago to discuss leaving the body.

Tonight, I’m seeing the Moon through dryer eyes.

No moonbow, though it’s wearing a partial eclipse like a mourning veil.

I don’t know when I’ll float out of this sick room, whether it will be through the door, the window, or the wall.

What I do know is that there are not 4 R’s.

There are 5.

And if I have a choice, I will pick the fifth exit.

Rainbow.

See you on the Hunter’s Moon!

—WD

This is the first article of yours that I’ve read. I felt a different type of pain during the last blue moon. It was the day I said goodbye to my best friend Jessie, the 16 and a half year old rescue dog pictured in my profile photo with me. I must have taken that back in 2011 or 12 while driving us back home from an afternoon in Bozeman. She has now - as people tend to say - gone across the rainbow bridge. Tears fill my eyes thinking of the moonbow you describe. My heart hurts so much. Thank you so much for writing and sharing your story. I wish you peace and healing.

This deeply resonates with me, as someone living with an unpredictable chronic condition. In my darkest moments, I imagine my body dissolving, painlessly evaporating. I hope your pain eases as I write, and that you rise to witness and experience many more rainbows.