Dear Lunatics,

This past month, you may have seen a flurry of panicked headlines about something called “Moon wobble.” Apparently, in the next decade, alterations in the moon’s orbit will result in catastrophic coastal flooding.

I dismissed these articles, which struck me as nothing more than paranoid clickbait.

But here we are, on the evening of a full moon, clinging to our flashlights as a tropical storm rages outside, making regular trips down the cellar stairs in our socks to check for sogginess from flash flooding.

If you were hoping to see the Sturgeon moon in all its glory, you can probably forget it. The cloud cover (at least in New England) is total.

Even on a night that’s not storm-tossed, the moon can play hard to get.

Earlier this week, I watched as tattered clouds played a sort of shell game with the glowing orb. The moon flashed in and out of view like a quarter passing through the deft fingers of a magician. And like watching a magic trick, it was both frustrating and mesmerizing.

In the world of magic, the moon is the white whale.

It’s on every magician’s bucket list.

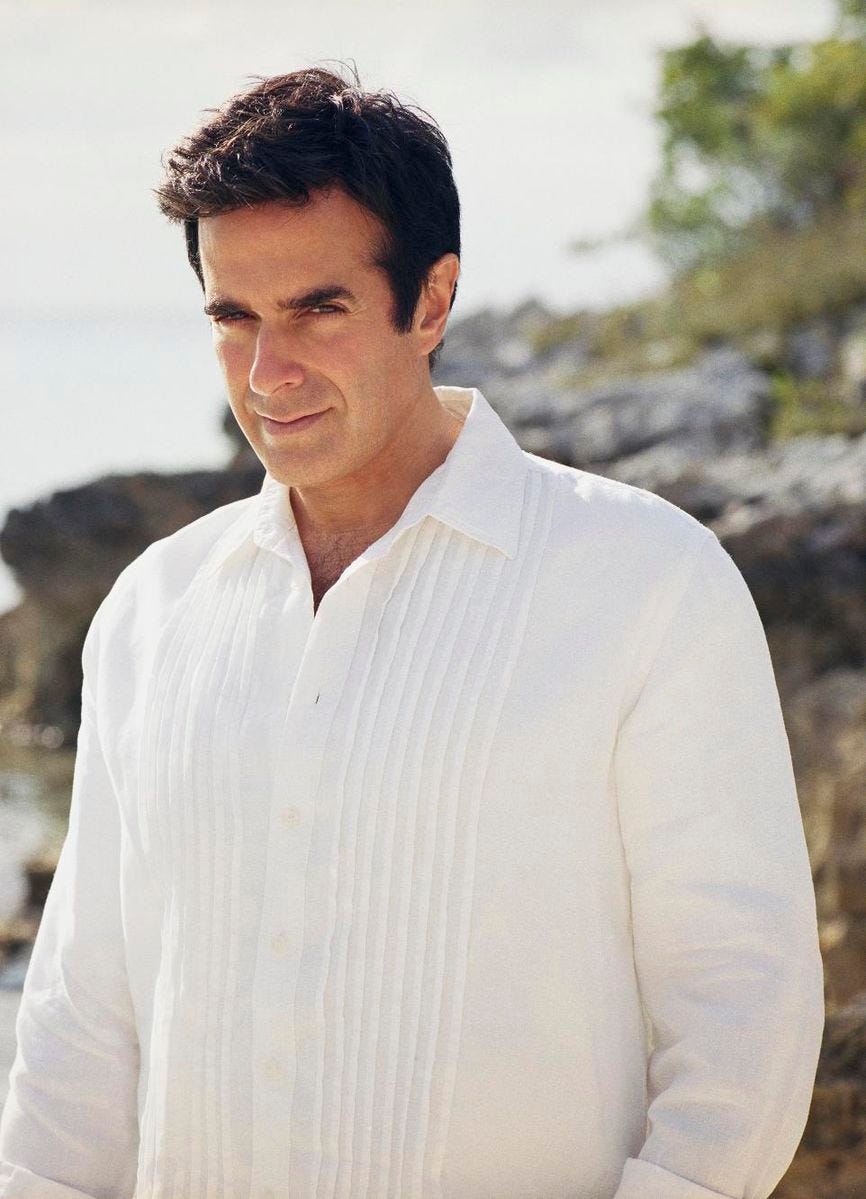

David Copperfield has pledged to make the moon vanish from the sky before he retires, though he first intends to put a woman’s face on Mount Rushmore and straighten the Leaning Tower of Pisa.

Franz Harary, who disappeared a NASA space shuttle and the Taj Mahal, boasted to a newspaper that he would make the moon disappear next. “I like manipulating large objects,” he explained.

And the Indian magician Gopinath Muthukad, who once made a local government official disappear on stage to wild applause, announced in 2011: “My greatest magic trick will be achieved when I make a full moon vanish, and it will happen soon. Everyone, everywhere, would see it disappear."

But these promises were all made ten years ago.

And in the past decade, not one of these mages has made any progress toward temporarily vaporizing the moon.

While the brotherhood of 21st-century magicians remains flummoxed, perhaps they should look to the women of the ancient world.

The witches of Thessaly, who operated in northern Greece from the 5th to 1st century BC, were famous for their ability to “draw down the moon.”

Evidently, these sorceresses could pull the moon out of the sky and extract its juices, using this “moon foam” to brew love potions and revive the dead.

Such a magical feat came at a high price: the witch was required to sacrifice an eye or a child to make the spell work.

Hippolytus, a third-century bishop, published a scathing exposé on the “Thessalian trick.” He sought to debunk the witches’ lunar “magic” by explaining how candles, mirrors, and pulleys were used to create the illusion.

This was one salvo in a war that has been raging for centuries.

And no, I don’t mean the war between the Church and powerful women.

I mean the war between magicians and those who reveal their secrets.

It’s only natural, after seeing a magic trick, to demand to know how it was done. We’ve all had the urge to tackle and frisk a stage magician who has just made the Ace of Spades melt into his sweaty palm.

But once you learn the secret behind a trick, the magic instantly dries up. And the professional magician has lost an illusion that probably took a thousand hours of practice to master.

There are other reasons that magicians guard their secrets.

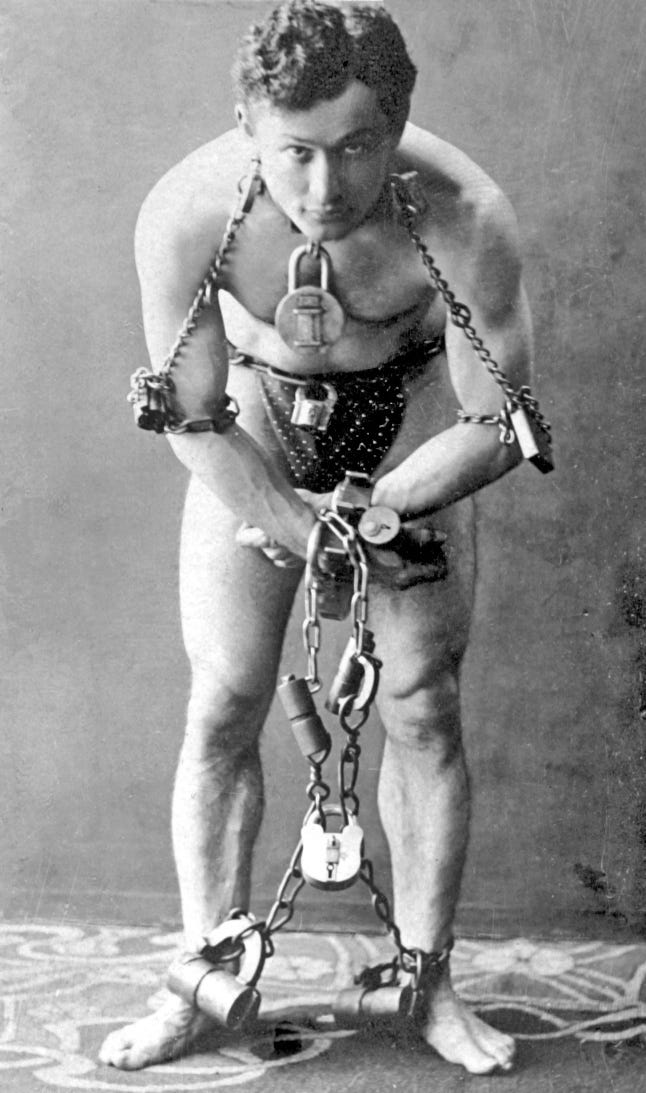

While on tour in England, Houdini was approached by a group of notorious thieves and bank robbers and offered a small fortune to establish a school of burglary. Houdini, who could escape a jail cell while handcuffed and naked, turned them down. “If I had chosen to reveal my secrets,” he later said, “no home or bank in the world would be safe.”

And then, of course, there’s the money.

David Copperfield takes extreme measures to protect his secrets, and who can blame him? He’s grossed over $4 billion in ticket sales, outstripping every other solo entertainer in history.

The blueprint for just one of his illusions would be as valuable as the recipe for Coke or the password to a bitcoin fortune.

Which is why I was stunned to learn that Copperfield recently divulged the secrets behind his major tricks—every last one of them.

He contributed these secrets, along with the details behind his proprietary magical technologies, to The Lunar Library—a backup of accumulated human knowledge etched on nickel plate and sent to the moon aboard Israel’s Beresheet spacecraft in 2019.

Unfortunately, the lander suffered a last-minute failure during descent and slammed into the Mare Serenitatis at 2,000 miles per hour, scattering wreckage far and wide across the lunar surface.

“We have either installed the first library on the moon, or we have installed the first archaeological ruins of early human attempts to build a library on the moon,” said Arch Mission Foundation co-founder Nova Spivack.

It’s strange to look at the moon, knowing that the instruction manual for the most lucrative magic show ever devised is somewhere up there, buried under a shallow layer of dust and regolith.

If any treasure hunters or rival magicians want Copperfield’s secrets, they’re right there for the taking.

All you have to do is draw down the moon.

Department of Call Backs

As I mentioned a few moons ago, the Kepler Space Telescope—a now-defunct spacecraft orbiting the Sun—is carrying one of my poems on board. In a surprise twist, the retired Kepler is back in the headlines.

Pouring over data collected by the telescope back in 2016, researchers have discovered evidence of a mysterious breed of planets that are free-floating, unbound to a host star, waltzing through deep space without a partner.

These planetary loners are difficult to spot. The lead author of the study, Dr. Iain McDonald of The University of Manchester, UK, described his team’s work thusly:

“These signals are extremely difficult to find. Our observations pointed an elderly, ailing telescope with blurred vision at one the most densely crowded parts of the sky, where there are already thousands of bright stars that vary in brightness, and thousands of asteroids that skim across our field. From that cacophony, we try to extract tiny, characteristic brightenings caused by planets, and we only have one chance to see a signal before it’s gone. It’s about as easy as looking for the single blink of a firefly in the middle of a motorway, using only a handheld phone.”

—The University of Manchester News

So there you have it. Even in its dotage, Kepler is lighting the path toward potential contact with alien life, thereby increasing the probability that my poem will one day be read by an extraterrestrial, which will be a really nice addition to my CV.

Moon Art

Last month, I put out an open call to Lunar Dispatch readers for any photos, drawings, paintings, or elaborate Play-Doh constructions of the Moon they may have—and oh boy, was my call answered.

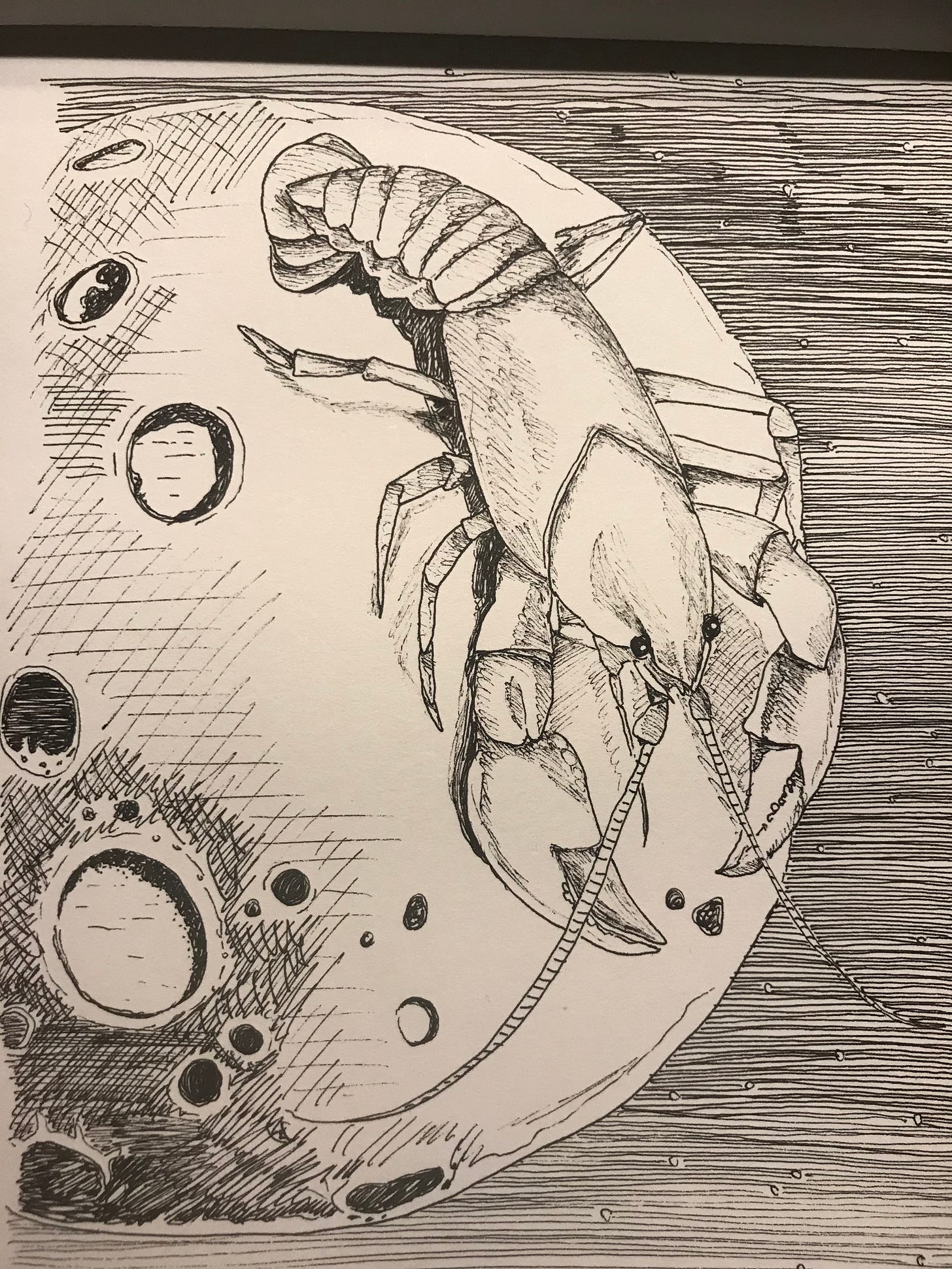

This fantastic drawing comes from Sarah Courchesne, who composes her own Substack newsletter called Ephemeroptera.

This lunar crustacean reminds me of the “Great Moon Hoax,” which took place 186 years ago this week. The New York Sun published a series of six articles, purportedly written by the former president of the Royal Astronomical Society, claiming that telescopic investigation of the Moon revealed a cratered surface teeming with bizarre creatures, such as herds of miniature bison, beavers that walk on two feet and live in huts with smoke-emitting chimneys, and winged orangutans aka “man-bats.”

The Sun’s circulation skyrocketed as the public lapped up the story, and I can’t help thinking that Sarah’s drawing would have made a perfect front-page illustration, waved around on every crowded street corner by the newsboys of New York City.

If you have any moon-related art you’d like to share, please send it to willdowdwriter@gmail.com, along with your name (and any relevant links) for credit.

Department of Gratitude

My thanks to Dr. Larry Krumenaker, an Alabama-based professional astronomer, educator, journalist, and prolific popularizer of science, for his recent Lunar Dispatch shout-out in his own Substack newsletter. For those of you hungry for more interstellar news, please check out Dr. Krumenaker’s bimonthly The Galactic Times newsletter, as well as his The Classroom Astronomer newsletter, which covers topics in astronomy education of all levels.

Shameless Self-Promotion

While I haven’t published so much as a haiku this past month (what can I say, it’s the summer), new readers to The Lunar Dispatch may enjoy my first book, Areas of Fog, which you can learn about here.

PS. If, like me, you read with your ears, Areas of Fog is also available as an audiobook via Audible and Itunes.

I had fun recording the narration, though as someone recovering from a Boston accent, I found certain words (peculiar, February, murder) to be an existential struggle.

Best of luck to those of you in the path of the hurricane. I hope that the tree branches swaying over your homes hold strong and that your lights (and air conditioning) stay functioning throughout the night.

See you all on the Harvest moon!

—WD