CROW MOON 2024

The Shadow of a Crow in Tokyo

Dear Lunatics,

Some of you may have stayed up to witness last night’s penumbral eclipse, and while it was not especially dramatic—just a shadow slowly crossing the Moon—I hope it wet your beak for the upcoming solar eclipse on April 8th.

Tonight’s full moon is known as the Crow Moon since, for northern tribes of the US, the cawing of crows declared the end of winter.

Crows are, arguably, the cleverest of animals, avian Ivy Leaguers whose intelligence rivals that of the average seven-year-old child.

They have a savant-like recall of human faces. (If you’re passing under two crows chattering to each other, they are probably gossiping about you.)

They also hold funeral services for their fallen brethren.

On a walk, I once came upon one of these solemn ceremonies—a black body lying in the road, claws up, and a few dozen mourners, smartly dressed in black, screeching in nearby branches. I slowly backed away.

But the most brilliant crows—the true geniuses of the Corvid family—are the jungle crows of Tokyo, Japan.

They use crosswalks.

They operate water fountains, turning the handles slightly when they want a drink and cranking them all the way when they want a bath.

They’ve even been known to place walnuts under the tires of cars idling at red lights, knowing that the otherwise unbreakable shells will soon be cracked open.

The jungle crows are also a dangerous nuisance. They have no fear of flames and routinely steal lit candles from shrines—they have a taste for the melted wax—and start massive forest fires in the process.

They’ve been known to purloin soap bars from public bathrooms. (They don’t eat soap; apparently, the bars are a luxury item for them.)

Worst of all, they use stolen clothes hangers made out of wire to build their nests in power lines, a practice that has caused widespread blackouts and brought high-speed bullet trains to a screeching halt.

The Tokyo authorities have spent millions of yen on the problem, employing a full-time Crow Patrol to hunt down and dismantle these clothes hanger nests.

But the crows are too smart. They’ve begun constructing “dummy nests” to distract the Crow Patrol from their actual nests, which are perched on higher-up junction boxes.

As Michio Matsuda, a board member of the Wild Bird Society of Japan, told the New York Times: “We are not sure sometimes who is smarter, us or the crows.”

So what makes the crows of Tokyo so diabolically clever?

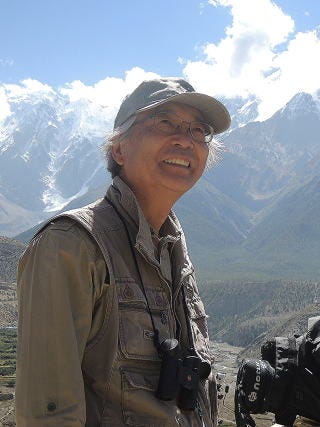

If anyone on the planet could solve this riddle, it would be Hiroyoshi Higuchi, Professor Emeritus at Tokyo University, an ornithologist who has researched these beady-eyed birds up close for half a century.

When I reached out to him, he gave me a simple answer:

Garbage.

“[I]n Tokyo, it is difficult to place big garbage buckets on narrow streets with limited extra space,” Professor Higuchi wrote to me. Therefore, people leave their garbage in clear plastic bags outside their homes, which allows the crows easy access to the food scraps.

According to Professor Higuchi, having their meals served in convenient to-go bags provides the crows of Tokyo with time to explore, play, and develop behaviors unseen among other members of their species.

The Professor has spotted crows balancing on electrical wires with one foot, rotating their body like practicing gymnasts. He’s even caught them tossing balls at tennis nets. Next thing you know, they’ll be writing poetry in the white sand of the city’s Zen gardens.

Tokyo never would’ve become the Renaissance Florence of crows without its notoriously narrow streets—some only two feet wide.

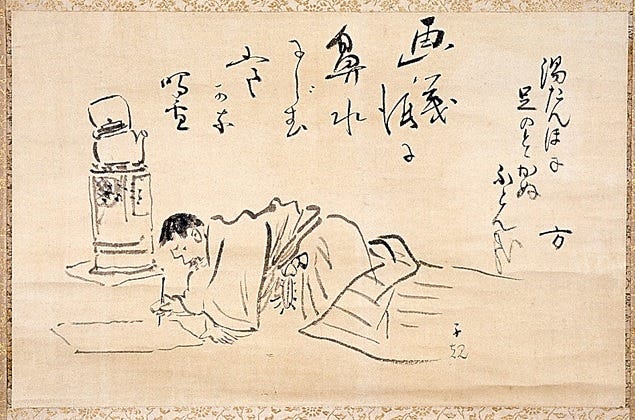

It was on one of these narrow streets that an invalid once lived. Confined to bed for almost seven years, the young man whiled away the hours painting and writing haiku while lying on his back.

There was no cure for tuberculosis of the spine in 1900, and the only relief the man found from his blinding pain came from his morning dose of morphine.

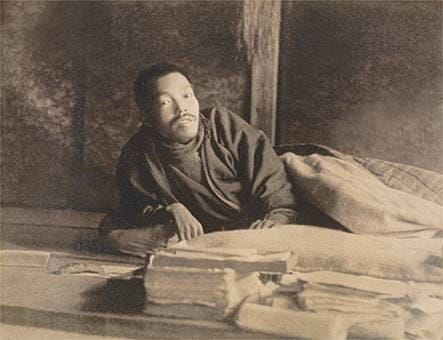

He took on the penname Shiki after the Japanese word for “cuckoo,” a bird that, legend had it, coughs up blood as it sings.

The tubercular Shiki had been coughing up blood for over a decade.

Shiki wished he could go mad to escape the pain, but he was, regretfully, hopelessly sane.

Suicide was never far from his mind and the means never far from his fingers. Rattling in his paint box was a blunt penknife. The only thing that stopped his hand was his fear that he would botch the job and add to his physical suffering.

It was in dreams that Shiki found true freedom from pain, as he flew weightlessly over the gabled roofs of the city.

It was always the crows that woke him at dawn.

At the time, crows were an omen of death: if one roosted on your eaves after nightfall and cawed, someone in your household was not long for this world.

I doubt Shiki wouldn’t have minded if a murder of crows descended on the roof of his family’s home.

In his diary, Shiki recorded a fantasy, or perhaps dream, of visiting the underworld and confronting Enma, the Lord of the Dead.

“I tell him that I am there to ascertain why no one from his bureau has come to fetch me yet, even though I am ready and waiting to be taken away, and that I wish to know when I can expect someone to come,” Shiki wrote. “At once, Lord Enma obligingly looks in his register for 1901, but cannot find my name. He gets a little flustered as he searches, and great beads of sweat roll down his face, but finally he discovers my name, crossed out, in the register for May 1897.”

Lord Enma summons his demon underlings and asks why they hadn’t fetched Shiki when his time came up four years prior. The demons blame the narrow, twisting streets of Tokyo.

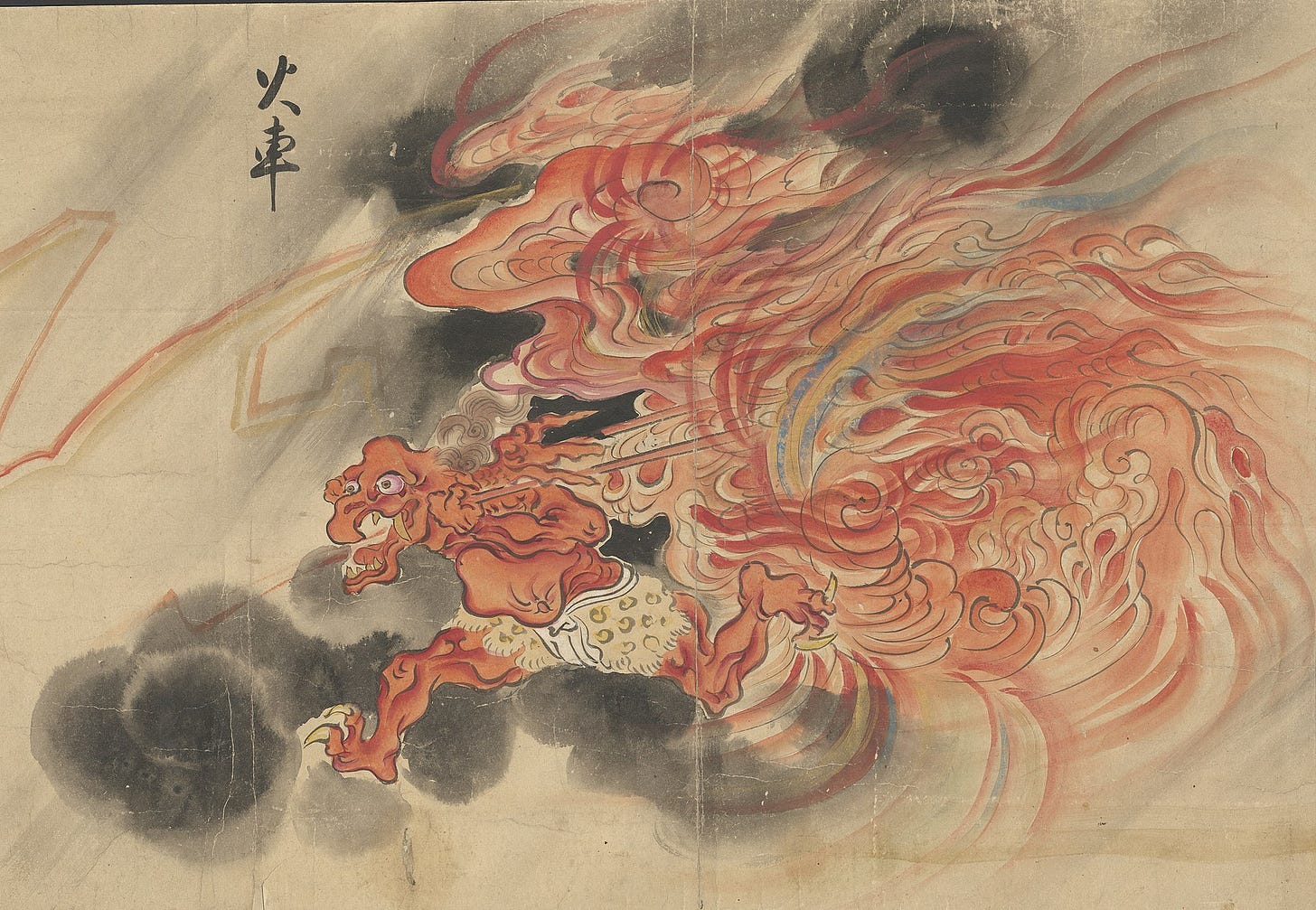

According to them, Shiki’s street, called Nightingale Lane, was “too narrow for the Cart of Fire to pass through.”

In restitution for their mistake, the Lords of the Underworld promise Shiki another ten years of life.

Shiki is appalled.

"‘What a terrible idea! No one would mind another ten years of life if he were healthy, but if I am to pass my time in the kind of pain I'm enduring now, I want to be taken away as soon as possible. I couldn't stand another year of this torture."

Lord Enma offers to collect him later that same night, which appalls Shiki just as much.

Tonight is too soon, he laments.

Shiki’s physical suffering must have been unbearable if he would descend to the underworld and ask to speak to the manager because his ride on the Cart of Fire was late.

In Buddhist mythology, the Cart of Fire is a flaming chariot that snatches up dead bodies and carries them to Hell.

At many Japanese temples, funerals were performed twice, the first time with a rock inside the coffin.

Like the crows with their dummy nests, the mourners hoped the demons would seize the first coffin and miss the real one.

I’m three moons away from my seven-year anniversary as an invalid.

In all these years, Shiki has been my most trusted doctor, and I’ve found his prescription the most effective: medicinal beauty.

From his sickbed, Shiki watched the moonlight drench the garden outside his home. He watched the canaries and zebra finches tremble in the birdbath beside his window. And he watched the goldfish circling in a glass bowl on his desk.

The world presents us with an endless procession of sensations, which most people ignore. But when pain cracks you open like a walnut under a tire, you are defenseless against these small pleasures.

“A sensation may last only a second, but it is a second that will never return,” Shiki wrote. “I refuse to let such moments slip by.”

I’ve tried to follow suit. I’ve watched the moonlight fan across my room, the blackbirds and sparrows cling to my wind-rocked birdfeeder, and my goldfish stare back at me with his inkspot eyes.

In a narrow life, you seek out any scraps of beauty you can find.

Until your time runs out.

On the morning of September 18th, Shiki was weak and racked with coughing. His sister Ritsu held up his drawing board so he could write his farewell poem:

The sponge gourd has flowered!

Choked with phlegm,

I become a Buddha.

Though he refers to himself as a Buddha (a dead man), Shiki summoned the strength to write a second poem.

Gallons of phlegm.

Too late

even for sponge gourd juice.

The fluid squeezed from a sponge gourd, a fruit that grew in Shiki’s family garden, was believed to relieve coughing and clear up phlegm, but only if its fluid was collected on the night of the full moon.

It was the day after the full moon.

Before he collapsed from exhaustion, Shiki wrote a third and final haiku:

They didn't even gather

the sponge gourd juice

two days ago.

How must Ritsu have felt, holding up her brother’s paper, as he scrawled his last words—a parting shot at her for not stockpiling the sponge gourd medicine when she had the chance?

Shiki slipped into a coma and died that night. He was 34 years old.

In his final poems, you can see Shiki’s three stages of confronting death—first, a touch of gallows humor (a Buddha stuffed with phlegm); second, a sigh of resignation (that sponge gourd water wouldn’t have helped anyway); and finally, a squawk of resentment (at least he could’ve tried the sponge gourd water if his family and friends had cared enough to collect it).

The haiku masters of old, having practiced non-attachment, were supposed to greet death with a certain melancholy lightness.

But it can’t be easy to keep one’s cool when you can hear death flapping its wings, soaring down your narrow street.

Besides, Shiki had learned long ago that death was not the true test.

As he wrote in A Sixfoot Sickbed, “I had mistaken the "Enlightenment" of Zen: I was wrong to think it meant being able to die serenely under any conditions. It means being able to live serenely under any conditions.”

How we live is what matters.

And how much beauty we can steal from the world.

Shiki, the cuckoo bird who lived on Nightingale Lane in the city of crows, stole more than most.

After all, there is only one creature on Earth able to outsmart a crow.

It's the cuckoo, who sneaks its eggs into the nests of crows, who mistake them for their own and warm them under their dark, iridescent feathers until, at long last, they crack open.

***

See you on the Pink Moon!

—WD

This is beautiful, Will - and it’s very special to read it from Tokyo! I’m off to look for crows.

What a lovely,moving piece. I will go to sleep tonight imagining crows writing and reciting poems.