Dear Lunatics,

I was nine years old when I saw my first “real” alien.

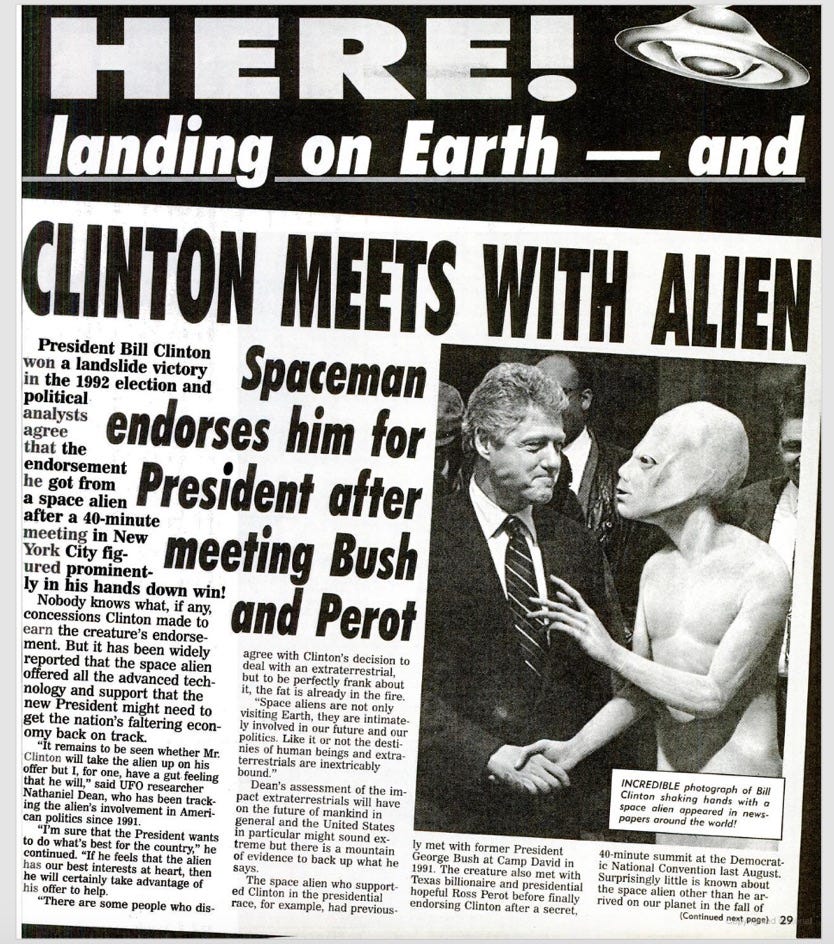

I was in the supermarket checkout line with my mother, trying to sneak packs of gum and candy bars unnoticed onto the conveyor belt, when a newspaper headline caught my eye. Apparently, an extraterrestrial had not only met with Bill Clinton but had formally endorsed him for President.

Being nine, I was not especially interested in the machinations of partisan politics, but the hairless, long-fingered grey alien was hard to ignore.

I snatched up the newspaper and flipped through its pages, discovering that not only extraterrestrials were real, but so were werewolves, vampires, and the Loch Ness monster.

I knew it, I thought to myself.

As soon as I got home, I began collecting a bag of weapons to protect myself.

The closest I could get to wooden stakes were, pathetically, pencils.

Fortunately, I came from a hunting family with a lax approach to weaponry, so I found other tools at hand.

It was only when the next full moon was imminent and I asked my mother for something silver (preferably bullet-shaped) that she disabused me of my mistaken beliefs.

What I had read may have looked like a newspaper but was in fact something called a tabloid.

Unloading the arsenal I’d assembled under my bed, I resolved to check my sources in the future.

Which is why I have checked, double-checked, and triple-checked that the recent paper published in Philosophy and Cosmology—a paper that has caused a global media storm—was indeed written by research scientists from Harvard University.

According to “THE CRYPTOTERRESTRIAL HYPOTHESIS: A case for scientific openness to a concealed earthly explanation for Unidentified Anomalous Phenomena,” an alien species may have alighted upon Earth at some point in the distant past and “taken up residence underground or underwater, or otherwise concealed itself nearby.”

The most likely hiding place, according to the scientists?

The far side of the Moon, of course.

When I read this research paper stamped with the Ivy League’s imprimatur, I felt as though I were back in that supermarket checkout line, mouth agog as my assumptions about reality were bagged up and sent packing.

It’s not the first time Harvard has done this to me.

One afternoon many years ago, I sat fidgeting in an overheated Harvard seminar room. It was a writing workshop and I had just read aloud my poem, which I was now waiting for my classmates to dissect like a body recovered from Roswell. But before anyone could so much as raise a scalpel, the professor, who had the wild hair and penetrating eyes of a fortune-teller, held up her hand, bringing the class to a halt.

It was clear that something in my poem, which had used alien abduction as a metaphor for something or other, had stirred a memory inside her, and she was debating whether to share it with us.

After a long pause, the professor seemed to reach a decision. She grabbed an empty basket and passed it around the room. “All electronics inside,” she commanded. When the basket returned to her, she inspected our phones, making sure none was recording, then put the basket on the floor and slid it with a boot heel under her chair.

With her eyes fixed on a fireplace that had probably gone unused since the 19th century, she began to tell a story from her past.

Here are the bones of her story, as best I can recall:

One summer when she was young, the professor fell in with a group of friends who had a secret. A secret they eventually divulged. There was a special hill just outside town. If you climbed this hill around midnight and waited patiently on its crest, eventually a UFO would swoop overhead, suck you up in a beam of light, and whisk you away.

Her friends did it all the time and, if she wished, the future professor could tag along with them on their next night flight.

She agreed.

But when the time came, and she was trudging up the appointed hill in the pitch dark, her courage failed and she fled from the summit. She took up a position on a nearby mound, crouching in the grass, watching the dark silhouettes of her friends on the hilltop. She waited for something to happen. And then it did. A UFO descended from the clouds, inhaled her friends in one bright gasp, and zoomed into the night.

And so the summer passed, her friends regularly taking the Midnight Special while the future professor watched from a safe distance. In the autumn, she moved away for school. She vowed to keep in touch with them all—and she kept her promise, though she wished she hadn’t.

One by one, over the years, each of her old friends shot themselves in the head.

Why they did this, she couldn’t say. None of them had left notes.

But she suspected her friends found they could not live normal lives, nor relate to normal people, after what they had experienced.

They had become too different.

They had become too alien.

“But don’t worry,” the professor assured me and my stricken classmates. “The UFOs won’t take you unless you ask.” In a swift, almost compulsive gesture, she raised her hands toward the ceiling, her many bangles clinking around her wrists. “Don’t take me,” she said firmly. “I don’t want to go. I know how it ends.”

Then she retrieved the basket from under her chair, we regained custody of our phones, and the class eviscerated my poem.

A shiver runs down my spine when I remember the professor imploring the aliens not to take her, assuming they were listening to us at that very moment—at every moment.

And maybe they are.

Over the past five years, the American physicist James Benford has advanced a fascinating—and utterly chilling—proposal that extraterrestrials may have left probes lurking in Earth’s orbit.

These listening devices, he maintains, may have been recording us since we first crawled out of the oceans.

Unlike SETI (the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence Institute), which hopes to catch a signal from the wide expanse of outer space, Benford thinks we should check our pockets first. The alien artifacts he describes would be concealed on near-Earth objects, piggybacking on asteroids or planted on the Moon.

Over email, I asked Dr. Benford how we can comb the Moon for alien devices. A search party of astronauts dragging rakes through moon dust?

“Actually,” he wrote back, “the efficient way to see if there are any signs of [extraterrestrial intelligence] on the Moon is to remember that we have had the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter in low orbit around the Moon since 2009. It has taken about ~3 million images at high submeter resolution. We can see where Neil Armstrong walked! The vast majority of the photos have not been inspected by the human eye.”

According to Dr. Benford, only an AI-powered system will be fast enough to flip through the LRO’s 3-million-picture photo album and find a trace of ancient alien technology.

Until then, I suppose, we’ll just have to watch what we say.

Especially in the Oval Office.

When he took up residency in the White House, President Biden asked NASA if he could borrow a 0.7-pound moonrock to decorate his shelves as a poignant reminder of America’s past accomplishments.

Skeptics always ask why aliens don’t simply land on the White House lawn, but why should they if they’ve already bugged the place?

Of course, the bigger question is why an extraterrestrial civilization would even be interested in us, especially if their only window into humanity has come from close monitoring of the activities inside the Oval Office.

One possible, albeit farfetched, reason is that aliens are us from the future.

The recent Harvard paper—the one that floated the concept of Moon-dwelling ETs—had a third author: Dr. Michael Masters, an anthropologist from Montana Tech.

In his two published books, Identified Flying Objects and The Extratempestrial Model, Masters posits that aliens may be humanity’s future descendants who have traveled back in time to study their evolutionary past.

As part of his argument, Masters cites the process of neoteny, a trend in hominin evolution that leads to the retention of childlike features in adults. (As they evolve, some species tend to look more and more like their juvenile selves.)

And what could be more horrifyingly childlike than the stereotypical grey aliens—those small-bodied, large-brained, bulbous-eyed, hairless, bipedal beings that spill out of dazzling spacecraft according to so many experiencers?

I don’t imagine it’s easy to maintain your professional standing when your research prompts headlines such as: UFOs are time machines from the future, professor claims.

“The stigma that exists is real,” Masters says.

As a poet, I know just how he feels.

Tell the stranger sitting next to you on a plane that you’re a poet and see how quickly they become absorbed in the flight safety manual.

In many ways, the ufology community and the poetry community are not dissimilar.

Both are intense collectives of true believers who, despite their relatively small numbers, pack convention halls in which the scene’s “celebrities” and hangers-on mingle, backscratching and backbiting, all bonded by a special interest in a mystery the rest of the world is either indifferent to or does not believe in at all.

Almost everyone wrote bad poems at some point when they were young, just as nearly everyone stood at their bedroom window at least once to search the night sky for a silver disk skirting their neighbors’ rooftops.

It’s a stage—something you’re meant to grow out of.

But a few of us never did.

This month’s full moon, known most commonly as the Buck Moon, is also called the Feather Molting Moon.

Fledgling ducks are currently shedding their down to make room for the adult feathers that will allow them to fly.

It’s a stressful time for these young, bald fowl.

They cower on windy nights among tall reeds, hiding from unseen aerial threats.

On these summer nights, we who preserved our childlike wonder lie on our backs on rippling grass and look up at the infinite space stretches before us.

We regard it with equal parts awe and terror.

For us, the sky is filled with fireflies and UFOs alike.

Soon, we trust, our feathers will come in.

Arched, metallic feathers that will encircle us, forming a sleek saucer that glints in the moonlight, lifting us upward at an impossible speed.

Up, up into a vast, crowded cosmos.

See you on the Sturgeon Moon!

—WD

"There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy."

That scene in the seminar room! You couldn’t make it up. Great writing, Will. As ever. Thank you.