Hunter's Moon 2022

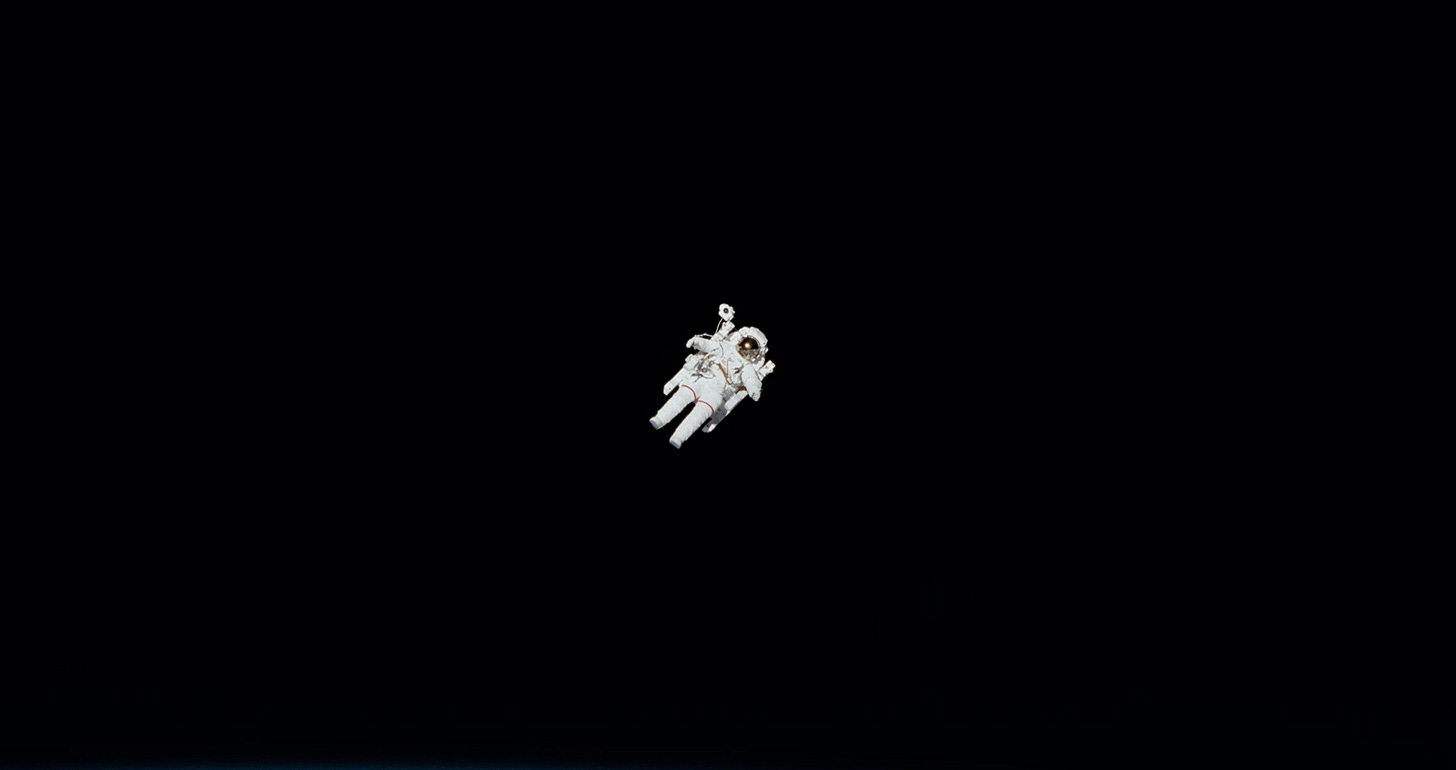

American Astronaut

Dear Lunatics,

Lately, I’ve been thinking about Apollo 11’s precarious arrival on the Moon.

Careering over a landscape of jagged lunar boulders, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin came within just a few breaths of crashlanding.

As Aldrin counted down the seconds until their fuel ran out, Armstrong was scanning for a patch of smooth Moon.

With less than ten seconds to go, he found it.

During this ordeal, both astronauts were wearing electrocardiogram sensors stuck to their shaved chests.

In Houston, Mission Control was tracking—among other things—the astronauts’ heart rates.

Surprisingly, Armstrong’s heart rate never flickered during the treacherous landing.

Even with the Moon’s teeth bared and ready to chew up their fragile aluminum craft, Armstrong had maintained the pulse of a cool-eyed predator on the hunt.

This story is retold in a book by Dr. Kevin Dutton, a research psychologist at the University of Oxford.

“Devastating fearlessness…may well habituate through repeated exposure to danger. But there are some individuals who claim it as their birthright, and whose basic biology is so fundamentally different from the rest of ours as to remain, both consciously and unconsciously, completely impermeable to even the minutest trace of anxiety…”

Dr. Dutton’s book is titled The Wisdom of Psychopaths: What Saints, Spies, and Serial Killers Can Teach Us About Success. In his book, he argues that we could all learn a thing or two about performing under pressure from our neighborhood psychopaths.

NASA’s astronaut selection process—a notoriously grueling two-year job interview—practically selects for people with a dash of psychopathy.

According to Jamie Barrett, a psychologist currently sitting on the astronaut selection committee, the ideal applicant is someone who is happy to work in a risky environment away from family and friends where they can’t feel the sun or the breeze.

In Tom Wolfe's nonfiction classic, The Right Stuff, the US Air Force pilot Chuck Yeager was depicted as the epitome of the fearless aviator.

For those who don’t know, Yeager was the first person to fly faster than the speed of sound.

He’s also considered by many psychologists to be on the psychopath spectrum.

A few months ago, I became worried that I myself might be a psychopath.

It started as all these things start—with a completely unsourced internet quiz.

Supposedly, if you can answer this single question correctly, you are a psychopath.

While at her own mother's funeral, a woman meets a guy she doesn't know. She thinks this guy is amazing—so much her dream guy that she falls in love with him then and there. A few days later, the woman kills her own sister. What is her motive for killing her sister?

According to reputable fact-checkers, this quiz is not reliable.

Psychopathy cannot be diagnosed by one question, let alone by an internet meme.

The answer to the question above, by the way, is that the woman in the story was hoping the guy would come to her sister’s funeral.

I didn’t get it right.

No, my answer was that the woman killed her sister because she was convinced funerals were a great place to meet guys and was hoping to meet a second dream guy—which I’m pretty sure is even more psychopathic than the actual answer.

Recently, scientists have proposed six genes linked to psychopathy and provided a chart showing which combination of these genes leads to which flavor of abnormality—sadistic personality disorder, antisocial personality disorder, etc.

With my recent DNA test results in hand, I nervously scanned for the six genes.

I had the first one.

I had the second one.

If I’d been hooked up to a cardiac monitor, it would have fried.

Fortunately, I didn’t have the other four genes.

Still, two were disconcerting enough.

Bracing myself, I ran my finger across the chart to learn what horrible psychological predisposition my particular cluster of genes indicated.

My finger landed on a single word:

Anxiety.

Fair enough, I thought.

So, what about the first man to walk on the moon?

Did Neil Armstrong have a touch of psychopathy?

His colleagues were struck by his unusual demeanor—the opaqueness that made him impossible to read and the quiet poise that was sometimes mistaken for coldness.

Yet, in my estimation, Neil Armstrong was decidedly NOT a psychopath.

The moment his boots reunited with the Earth, Neil Armstrong became one of the most famous humans alive.

A true psychopath would have relished the fanfare; Armstrong loathed it.

He hated being swarmed by strangers. Hated being touched and tugged by autograph hunters.

His globular space helmet had become a fishbowl and everyone wanted to tap the glass.

Most of all, Armstrong felt uncomfortable receiving all the credit for the work of the tens of thousands of people who had contributed to the Moon mission.

He wasn’t made for fame.

Reflecting on Armstrong’s discomfort in public, his wife Janet once said, “He’s certainly led an interesting life. But he took it too seriously to heart.”

If Armstrong wasn’t a psychopath, how do we account for his preternaturally low heart rate in the face of near-certain death?

Let’s look at his life experiences.

Armstrong flew 78 missions as a Navy pilot in the Korean War, at one point successfully bailing out of a fatally damaged jet that was heading for the ocean surface.

A year before the Moon Landing, Armstrong ejected from an out-of-control Lunar Landing Research Vehicle, suffering only "a hard tongue bite."

This sort of thing seems to have happened to Neil Armstrong a lot.

But that’s not all.

In 1964, Armstrong’s house caught fire in the middle of the night. After escaping with his wife and baby, he realized that his six-year-old son, whom he had woken and instructed to run outside, had remained cowering in his bedroom. With a wet towel over his face, the father rushed back into the burning house.

Armstrong, who traveled 240,000 miles to the Moon, would later say that the 25-foot crawl through the smothering, scorching smoke to retrieve his son was the “longest journey” of his life.

Of course, this nightmare pales in comparison to what Armstrong endured two years prior, when the family lived in a cabin on the edge of the Mojave Desert.

Whenever their two-year-old daughter Karen tottered around the yard, Janet would tie a bell on her back. That way, she could hear the bell jingling—ding-dong, ding-dong—over the howling wind.

But soon, the clang of Karen’s bell would have faltered as her gait became unsteady and she regularly fell.

They took her to the doctor, and six months later, on her parents’ wedding anniversary, she died of a brain tumor.

Armstrong showed no emotion at the funeral. He was back at work five days later. According to friends and colleagues, he never spoke about his daughter’s death.

Not once.

Maybe Armstrong’s heart rate was so low and imperturbable because his heart had already been so thoroughly broken.

There was one moment during the Apollo 11 mission when Armstrong’s heart rate did spike alarmingly.

In his final minutes on the Moon, Armstrong had to load and carry boxes filled with lunar rocks, then hoist them into the spacecraft. As he gathered his quarry, the astronaut’s cardiac monitor shot up to 160 beats per minute, freaking out ground control back in Houston.

Was Armstrong gripped by fear about the return flight home, which (though the public didn’t know it) was even more hazardous than the landing itself?

It doesn’t seem so.

A half-hour before he splashed down into the Pacific, when most of our hearts would be hammering wildly, Armstrong’s had returned to its usual 61 beats per minute.

I believe that Armstrong’s heart rate spiked while he was hauling those moon rocks for the simple reason that the man was a little out of shape.

Armstrong held a peculiar belief that each human was allotted a certain number of heartbeats at birth.

Armstrong didn’t work out, not even in the lead-up to the Apollo launch, because he preferred not to waste his handful of remaining heartbeats on something so foolish.

However, unbeknownst to Armstrong, his trip to the Moon did do lasting damage to his heart.

In 1991, he suffered a heart attack while skiing. In 2012, he was rushed to the ER for quadruple coronary bypass surgery.

He died from complications two weeks later.

It is now clear that exposure to deep space radiation left all the Apollo lunar astronauts with a significantly higher mortality rate due to cardiovascular disease.

It has been christened Neil Armstrong Syndrome.

On August 31, 2012 (which happened to be a blue moon), Armstrong’s family held a private funeral.

Two weeks after that, they scattered his ashes off the coast of Florida.

Many of us wonder why an astronaut would choose to be buried at sea.

Maybe it was Armstrong’s way of honoring his wartime service in the Navy.

Or maybe the introverted celebrity, who had spent half his life fleeing adoring crowds, did not think he could rest in peace with a never-ending procession of tourists trampling six feet overhead.

But tonight, I have a different theory.

If the Apollo 11 Lunar Module had been damaged upon touchdown, Armstrong and Aldrin would have been stranded on the Moon forever.

In this scenario, NASA planned to close down communication with the men, leaving them to starve to death or commit suicide in radio silence, while President Nixon would appear on television to deliver a prewritten eulogy.

It had also been decided that the funerals of the two astronauts would use the same ceremonial language reserved for burials at sea.

It would have been an eerie graveside service to attend.

Imagine a clergy member standing over an empty casket and proclaiming: We therefore commit their bodies to the deep to be turned to corruption, looking for the resurrection of the body when the seas shall give up her dead…

All the while, the mourning family would be trying desperately not to glance overhead where the day moon might shimmer faintly, a craggy crescent where their dearly departed were most likely still alive, shipwrecked.

We’ll never know why Niel Armstrong elected for a burial at sea.

Or what words his family proclaimed as they spread what remained of Neil Armstrong into the Atlantic Ocean?

Perhaps the Armstrong family chose to recite “Ariel’s Song,” a nine-line poem fished from Shakespeare’s The Tempest.

I believe this poem, which is one of the most common texts read at sea burials, would have spoken to the uncanny life of an Ohio farm boy who tilled lunar soil, and to the inwardly grieving father who may have hoped to find, in death, something that had lost long before.

Full fathom five thy father lies;

Of his bones are coral made;

Those are pearls that were his eyes:

Nothing of him that doth fade,

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange.

Sea-nymphs hourly ring his knell:

Ding-dong.Hark! now I hear them,—ding-dong, bell.

Next month is a Total Lunar Eclipse. You can visit this site to learn if and when the eclipse will be visible in your location.

See you then!

—WD

P.S. I heartily recommend First Man: The Life of Neil Armstrong by the historian James R. Hansen, whose original research provided many of the facts referenced in this post.

Thank you for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to this newsletter, which is as free as looking at the Moon.

And please consider sharing this post with some of your fellow Earthlings 🚀.

Always wonderful - but I loved your extra-psychopathic answer. I hope that doesn’t come off as psychopathic.

Your storytelling had me hooked. You gave great insight into how Neil

Armstrong ‘s history helped shape him into the man who was near perfect for the Apollo 11 mission and how he eschewed fame afterwards.