HUNTER'S MOON 2023

The Ghost Hunter

Dear Lunatics,

Tonight, the Hunter’s Moon rides.

It’s obvious why hunters love the Moon—especially at this time of year when the turkeys and deer are at their plumpest.

But criminals also consider the Moon a loyal friend.

Think about it: the Moon is the perfect accomplice. It’s a witness that never squeals on you. A flashlight that never gives away your fingerprint.

I’ve only ever heard one person disagree.

Harry Houdini.

In his 1906 manifesto, “The Right Way to Do Wrong: An Exposé of Successful Criminals,” Houdini claimed that housebreakers always consult an almanac while planning their heists. According to the magician, no self-respecting criminal would burgle a house on the night of the full moon, since its floodlight would illuminate the grounds. (Unless, of course, there was a partial eclipse like tonight…better check your locks before bed.)

Houdini had a high opinion of expert criminals.

“If the same amount of ability and talent that many a criminal exercises to become a professional burglar were applied to an honest pursuit, he would gain wealth and fame,” he wrote.

Houdini himself was proof of this assertion.

While on tour, the first thing Houdini would do upon arriving in a new city was to march down to the police station, where he would break out of jail, handcuffed and sometimes naked.

The local criminals took notice.

In England, Houdini was approached by a group of infamous thieves and bank robbers and offered a small fortune to establish a school of burglary.

He turned them down.

“If I had chosen to reveal my secrets, no home or bank in the world would be safe,” he later said.

Like every great magician, Houdini guarded his secrets with his life.

Aside from his brother Theo, an early collaborator, Houdini made one exception.

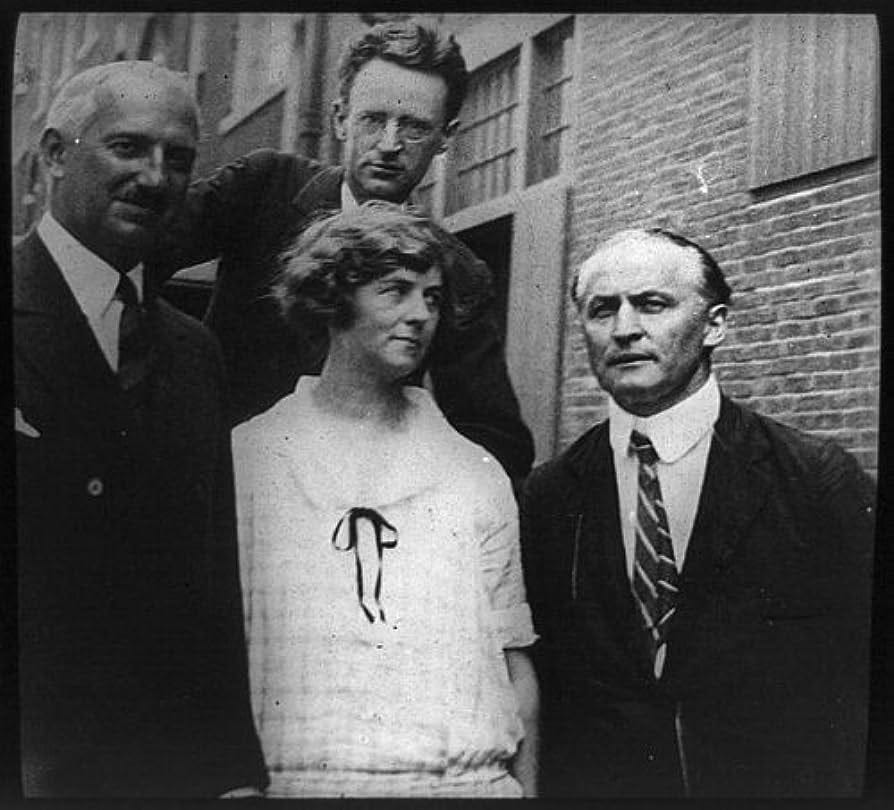

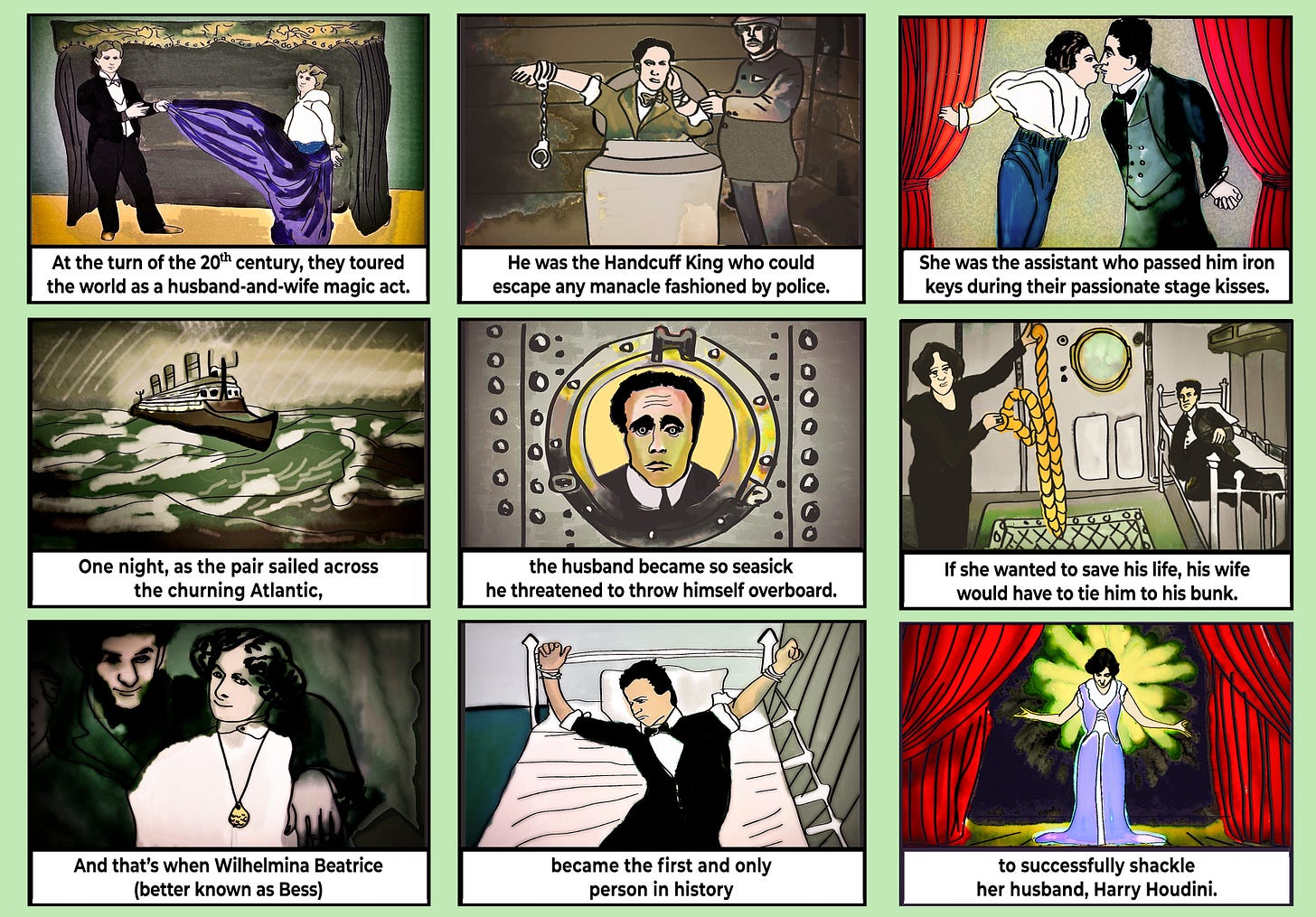

When he was twenty, he met an eighteen-year-old Brooklyn girl named Bess. After a three-week courtship, the two were married. Shortly after, Houdini decided to make Bess his stage partner. At five feet tall and ninety pounds, she would fit nicely into trick compartments and magic trunks. But before she could be brought into his act, Houdini needed to extract a promise. Bess must solemnly vow never to reveal the secrets behind his tricks.

This was not an oath that could be taken lightly. Late one night, Houdini led Bess into the country and brought her to the middle of a dark, deserted bridge. He waited for a distant bell to toll midnight.

Bess was prepared to swear her loyalty, but what would she swear on? Not a holy book, that’s for sure. Bess was raised Roman Catholic while Houdini (real name Erich Weisz) was of Jewish heritage—a fact that horrified Bess’s mother, who didn’t speak to her daughter for twelve years after her wedding.

I imagine Houdini and Bess on the bridge, looking around, surveying the barren marshland for something shared and sacred to swear upon.

At some point, one of them must have looked up.

It was a full moon.

Bess swore to the heavens that she would keep Houdini’s secrets for the rest of her life.

She was in—and thus began their husband-and-wife vaudeville act that took them across the country.

Years later, Bess would make a similar vow to Houdini; only this time, she swore to keep his secrets even into the afterlife.

The couple made a promise: whoever died first would reach out, if such a thing were possible, from beyond the grave. To make sure the surviving partner was not taken in by a fraudulent medium, they agreed to communicate exclusively in the private coded language they had developed for passing messages on stage.

Houdini knew something about fraudulent mediums—he had started out as one.

In their early twenties, Houdini and Bess, who were flat broke, joined a traveling medicine show as performing mediums. Whenever they rolled into a new town, Houdini would stroll the cemetery, noting down dates and names in his notebook. He’d also secretly pay a local for a briefing on their neighbors.

Though his spiritualist act was a money-maker, Houdini eventually retired it on moral grounds—he felt guilty for trifling with human grief.

He was done with the world of spirits forever.

Or so he thought.

In 1913, Houdini’s mother Cecelia died unexpectedly. The two had been incredibly close. The magician, who described his mother as a saint, was inconsolable.

In the years that followed this devastating loss, Houdini did something surprising: he attended hundreds of séances.

“I…would have parted gladly with a large share of my earthly possessions for the solace of one word from my loved departed,” he said.

Yet in séance after séance, Houdini never received word from his late mother. Although he had looked high and low for a psychic with the genuine gift, he found only scam artists and charlatans.

All mediums, Houdini decided, were “human leeches” siphoning “blood money” from their grieving “victims”—and someone needed to stop them.

Using his insider knowledge of stage magic, Houdini began to wage a one-man crusade against the Spiritualist community. Before long he was the world’s highest-profile debunker of mediums.

Around this time, the popular magazine Scientific American launched a controversial contest. It would award $2,500 to the first person who produced “a visible psychic manifestation” to the full satisfaction of its judges. Houdini joined a handful of scientists and parapsychologists on the judging committee.

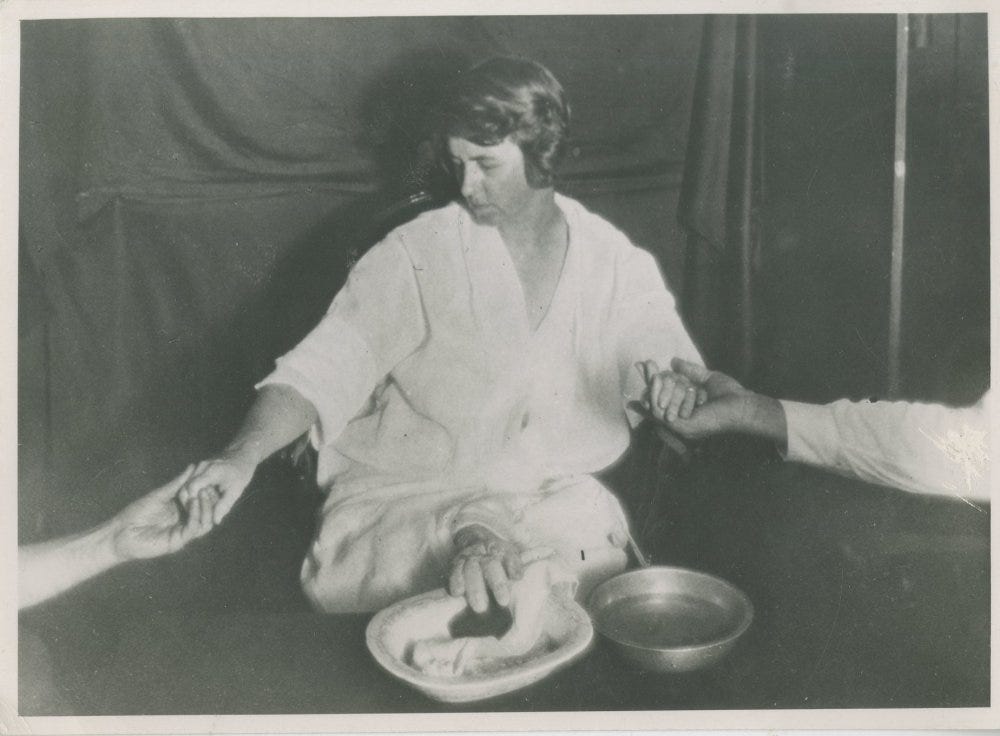

For the first year, the judges chased down leads on both sides of the Atlantic. No serious contender for the prize emerged until they encountered Mina Crandon, the young and fashionable wife of a well-connected Boston surgeon.

The Crandon’s apartment in Beacon Hill had become a kind of supernatural hub where the city’s upper crust would congregate for dazzling séances. To keep her real name out of the papers, Mina had adopted a professional alias: Margery.

In the summer of 1924, Houdini and his fellow judges traveled to Boston to test Margery’s purported psychic powers. On the line was not only Scientific American’s purse but also the reputations of both Houdini and the Spiritualist movement as a whole.

In the pitch dark of the séance room, this small group of skeptics and believers sat around a table, clasping hands. Then the medium manifested her greatest hits. The Victrola stuttered and went silent. There were mysterious whispers and whistlings. A bell enclosed in a wooden box at Houdini’s feet rang out insistently. The ghost of Margery’s dead brother spoke from beyond the grave. “You think you’re pretty smart, don’t you?” he growled at Houdini, before tossing a megaphone in his direction. The table itself rose off the floor and a cabinet was hurled violently across the room.

Houdini’s verdict?

Margery was a very gifted fraud.

In fact, he called her performance “the slickest ruse I ever detected.” He booked a show at Boston’s Symphony Hall where he exposed Margery’s tricks in front of a packed house. A month later, the Scientific American committee voted to deny her the prize. Later, the editor J. Malcolm Bird, one of the Scientific American committee members, admitted that he had colluded with the medium to produce some of her effects.

In the wake of this revelation, Margery’s reputation waned. Her circle of true believers shrank. Yet she wasn’t done with her arch-rival. During a séance in August 1926, she delivered a chilling prophecy: Houdini would be dead by Halloween.

Houdini had been buried alive, tossed off bridges in leg irons, and even sewn up inside the carcass of a giant leatherback turtle. But his actual end, when it came, was tragically banal.

After a lecture at McGill University, a college student named J. Gordon Whitehead talked his way backstage and found Houdini reclining on a sofa in his dressing room.

Whitehead announced that he wanted to test Houdini’s abdominal muscles, which rumor had it were iron enough to withstand any punch. Before the magician had a chance to brace himself, Whitehead—an amateur boxer—delivered five hammer blows to Houdini’s stomach.

Two days later, Houdini collapsed on stage. His appendix had burst and he had developed peritonitis. He hung on for one excruciating week. When he died, his wife Bess was at his bedside.

It was Halloween.

Bess was understandably heartbroken. She was more than just Houdini’s wife; she was his partner in magic. At times, she had mounted the stage and passed Houdini the key to his shackles in a kiss.

Now she prepared their greatest trick.

Beginning the following year, Bess dutifully held a séance every Halloween night, listening intently for her husband’s voice. After a decade of silence, she gave up. “Ten years is long enough to wait for any man,” she said.

It’s difficult to know how we should interpret Houdini’s after-death silence.

I believe he may have had good reason for keeping his incorporeal mouth shut.

The man who killed him, J. Gordon Whitehead, was an enigmatic figure who flits in and out of the historical record. We know that he was a student of religion, though he dropped out a few months after Houdini’s death. We know that he would later be arrested for shoplifting a book on occult sciences. And we also know that he would eventually become a reclusive hoarder and die of malnutrition.

But was Whitehead connected, as some have claimed, to the Spiritualist movement?

Was his fist the instrument of their revenge?

If so, can we really expect the ghost of Houdini to have whispered in Bess’s ear, thereby proving that the dead can communicate with the living? Wouldn’t that have handed an ultimate victory to the Spiritualists, his mortal enemies, who may well have sent an assassin to his dressing room?

After Bess died of a heart attack in 1943, her Roman Catholic family would not allow her to be buried alongside her Jewish husband.

But her Halloween tradition lives on.

Each year, Houdini’s most committed fans gather for séances on October 31st, holding out hope that their hero will make one last encore.

And I don’t blame them.

If anyone can slip through the veil separating this world from the next, surely it’s the man who in life could squeeze through the bars of any prison, trailing a molted straitjacket and heavy iron manacles that now held only air.

See you on the Beaver Moon!

—WD

P.S. Along with my lunar duties, I am also a cartoonist for The Boston Globe. If you enjoy this recent piece, follow me on Instagram, where I post my cartoons regularly. 🙏

*Note: A portion of this month’s newsletter was broadcast on WVIA’s ArtScene.

I remember a sort of biopic about Houdini starring the late Bill Bixby in the title role. NOW if I can find a link to it or a similar movie somewhere. My curiosity is reengaged.

As a Bess whose husband is dying I've been thinking a lot recently about Bess and Harry and his promise to get in touch, as it were. I've been thinking about what "forever" really means (and writing about it https://open.substack.com/pub/bessstillman/p/forever-is-short-long-time?r=16l8ek&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web) My husband and I are scientists, but also, we've chosen a few key words just in case the opportunity ever arises to have a post-mortem chat, just like Harry and Bess did. True love might be the greatest magic trick of all, and it seems like that, more than anything could be what would allow someone to shrug off the shackles of death, if such a thing is possible ,even for a moment. Here's hoping. (and here's to Houdini)