Dear Lunatics,

Exactly 19,100 days ago, Commander Neil Armstrong crawled out of a lunar module and dug his heels into the face of the Moon. “The surface is fine and powdery,” he radioed to Earth. “I can pick it up loosely with my toe.”

We all know how the flight controllers in Houston reacted (celebratory hoots and flag-waving). And we can well imagine how their Soviet counterparts reacted (loud swearing and vodka swigs).

But how did the rest of the country react?

On July 21, 1969, The New York Times asked a cross-section of public intellectuals and civilians for their responses to the world-shaking event. The resulting two-page spread makes for fascinating reading.

Was the moon-landing a triumph or a travesty?

The artists were divided.

According to the absurdist playwright Eugene Ionesco:

It’s an extraordinary event of incalculable importance. We are breaking down the wall of our smallness. We are demystifying the moon, and now anything is possible.

But the writer and microbiologist Rene Dubos fretted:

For thousands of years we have encouraged science fiction writers to entertain us with tales of various creatures supposed to live on the moon and on the stars. If nothing worthwhile can live on the moon we shall feel even more lonely in lifeless space…

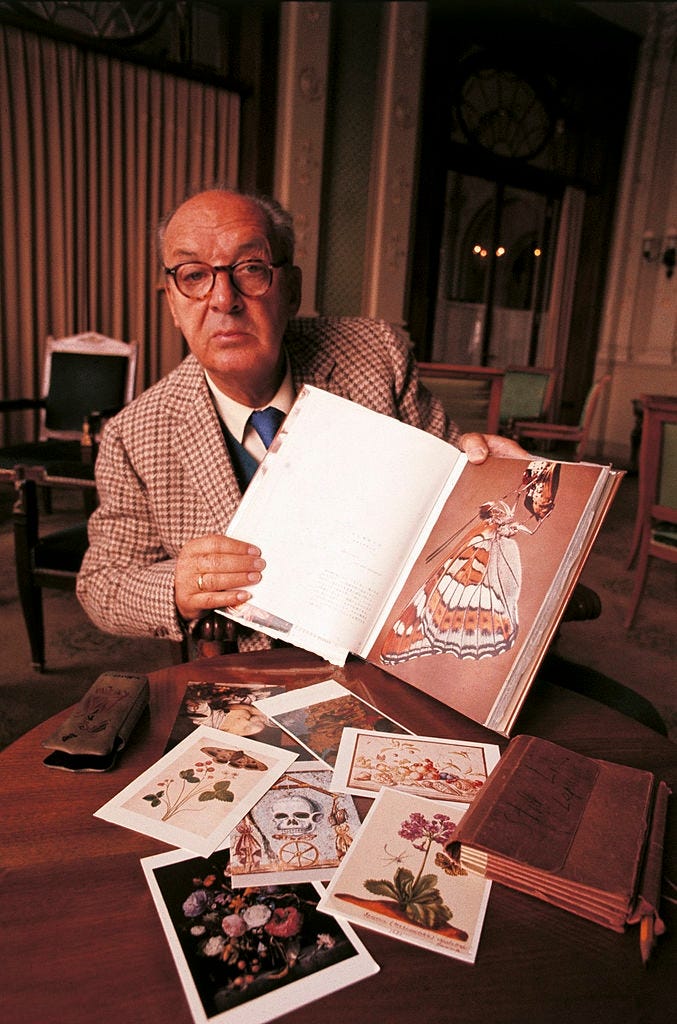

Meanwhile, the novelist Vladimir Nabokov was his usual arch self:

Treading the soil of the moon, palpating its pebbles, tasting the panic and splendor of the event, feeling in the pit of one's stomach the separation from terra... these form the most romantic sensation an explorer has ever known... this is the only thing I can say about the matter. The utilitarian results do not interest me.

Other responses took a mystical turn.

The moral philosopher Eric Hoffer mused on our collective pull toward the skies:

I have always played with the fancy that some contagion from outer space had been the seed of man. Our passionate preoccupation with the sky, the stars, and a God somewhere in outer space is a homing impulse. We are drawn back to where we came from.

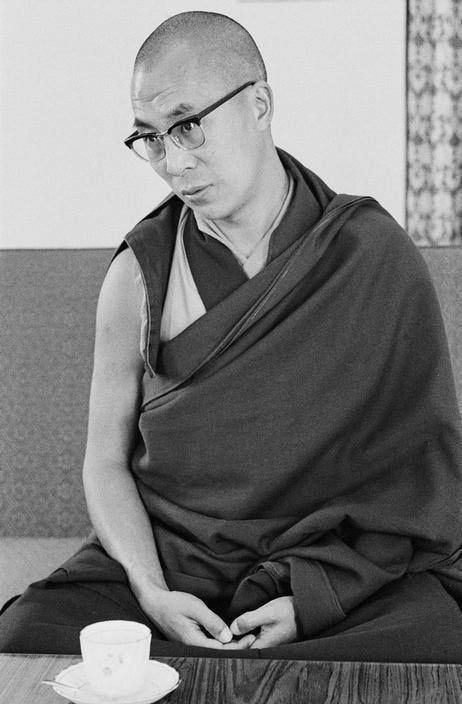

The Dalai Lama—34-years-young at the time—was filled with hope that space travel could expand our consciousness:

We Buddhists have always held that firm conviction that there exists life and civilization on other planets in the many systems of the universe, and some of them are so highly developed that they are superior to our own….Man’s limited knowledge will acquire a new dimension of infinite scope, development and dynamism. In this, the high degree of civilization developed in other planetary bodies will be of colossal help.

Most of the politically-active respondents were less than jubilant.

Saul Alinsky dryly encouraged the US President to get on the next rocket to outer space.

Jesse Jackson pointedly observed:

While our astrophysicists can figure out the formulas that make the amazing trajectories and landings possible, we can’t seem to get nutritionists and physicians to the shanties and shacks of Appalachia.

The most searing critique came from the poet June Jordan, who wrote a blistering, lyric response:

Nowadays the heroes go out looking for the cradle in the cold. They explore a cemetery for beginnings…

So the President declares a holiday. The country glorifies its landing outside the whole scene, outside the extraordinary, common kiss among peoples. Nobody boggles the mystery we, man and woman, used to offer the world.

How about a holy day, instead, a day when we concentrate on the chill and sweat worshipping of humankind, in mercy fathom? I mean, brothers and sisters, have you ever heard of children—bankrupt, screaming—on the moon?

As you might expect, technological enthusiasts like Henry Ford and Buckminster Fuller beat the drum of progress.

However, the historian Lewis Mumford saw the moon-landing program as a symbolic act of war:

In order to make this misappropriation of public funds and human energies acceptable, the Space Agency has turned the moon landing program into a national sporting event whose excitement is augmented by the fact that, as in speed racing, it provides a morbid thrill in the ever-present possibility of a spectacularly violent death. To further mask the real nature of this enterprise, the promoters of space exploration have made the credulous and the scientifically uninformed believe that a better future may await mankind on the sterile moon, or on an even more life-hostile Mars—as if such a change of scene would bring our sick rulers and their still acquiescent victims back to health.

Finally, while many entries expressed a childlike wonder at the moon-landing, The New York Times wisely solicited the opinion of an actual child.

The entry by Jim Aiello, a 12-year-old boy from Michigan, starts off as you might expect:

I’d like to be an astronaut. It sounds like a pretty good job to me. Good pay and you find something new every time you go up.

But a few paragraphs later, little Jimmy suddenly transforms into a terrifying Malthusian:

With the population explosion, more people are being born every day than are dying. If they find like they could live on another planet they’d try it out first and then use it to find a home for people. They can’t live on somebody’s front lawn.

I find it curious that a 12-year-old boy would be so concerned with keeping front lawns uncrowded.

But perhaps he had a paper route.

If so, I can only imagine the spring in his step as he delivered The New York Times on the morning of July 21st, 1969.

See you all on the Beaver Moon!

—WD

P.S. If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing (the newsletter is as free as looking at the Moon).

And if you already subscribe, please consider sharing the newsletter with some friends. Thank you!

Wonderful piece! Thanks for the walk thru history- I stayed up late with my dad to watch it happen, and remember it so clearly. I prefer the anti- intellectual reactions in this case.

This was amazing!!! As usual.