Dear Lunatics,

Tonight, the Pink Moon ascends in all its glory.

If you get a chance to step outside and see the Moon face-to-face, take particular notice of its pockmarks.

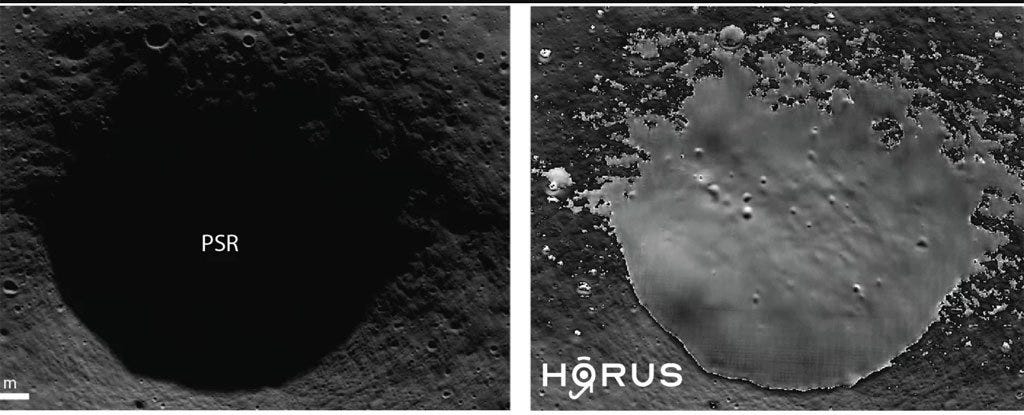

Some of these craters—formed by 4 billion years of asteroid bombardments—are so deep they exist in eternal night. They may even contain ice that’s been frozen for millions of years.

Understandably, these pitch-black craters have proved impossible to image…until now.

German researchers recently developed an AI program called HORUS that can map the Moon’s unlit craters, thereby shining a light that may guide future explorers on their lunar treks.

If you’re reading this on your phone, you’re holding in your hand a more powerful computer than the one that put humans on the Moon.

As technology advances exponentially, advanced artificial intelligence is not a probability—it’s an inevitability.

By the end of the decade, there will be machines smarter than the smartest human being.

By mid-century, there will be machines a billion times smarter than the smartest human being.

Compared to these contraptions, we will be like a beetle stuck in Einstein’s hair, a worm in Isaac Newton’s apple, a fly on Marie Curie’s blackboard.

What’s to stop AI from swatting us?

Mo Gawdat is an Egyptian entrepreneur and the former chief business officer for Google X.

In his new book Scary Smart: The Future of Artificial Intelligence and How You Can Save Our World, Gawdat argues that we should address the dangers of AI now.

Wouldn’t it be wiser to wrestle with this new technology while it’s still in its infancy, rather than waiting to negotiate our survival with a silicon god?

Gawdat proposes an intriguing call to action.

To ensure that our AI creations don’t exterminate us, we should stop thinking of them as menacing aliens.

We should think of them as our children.

“Instead of containing them or enslaving them, we should be aiming higher,” Gawdat advises. “We should aim not to need to contain them at all. The best way to raise wonderful children is to be a wonderful parent.”

I’m not a parent, but I have a nephew who recently turned three years old.

He can say the alphabet backward, identify shark species on sight, and read just about any text you put in front of him.

But his real passion is the night sky.

He doesn’t know the seven dwarves in Snow White, but he can spell the name of every dwarf planet (and their moons).

He’s still at the tail-end of potty training, but he can tell you all about Proxima Centauri.

The other day, he asked me to name some exoplanets, and when I didn’t rattle them off fast enough, he became impatient and instructed me to “Google it.”

Of all the celestial bodies, his favorite is the Moon.

Even on the coldest winter night, my nephew will pause on the short walk from house to car seat and spin in place, searching the sky.

He’ll point and say “waxing crescent.”

He doesn’t always get the Moon’s phase correct, and he hasn’t quite wrapped his head around the concept of the new Moon. (When the Moon is absent, his face makes an expression that says: where the hell did it go?)

But he did best me recently.

For a while, he’s been referring to the Moon as “Luna,” which I assumed was his own fanciful invention.

It turns out that Lūna, the Latin word for the Moon, is sometimes used for the sake of clarity if you are discussing—as my nephew often does—Titan, Europa, Ganymede, Callisto, and the other 171 moons that dot our solar system.

I don’t want to give the false impression that my nephew is a bow-tie-wearing prodigy in a Wes Anderson movie.

He’s equally enthusiastic about ice cream, trampolines, strangers’ dogs, and playing with friends.

And I doubt that this encyclopedia of cosmic facts will stick permanently in his brain.

But even if he does forget that Jupiter’s Great Red Spot is a “blazing storm,” I hope he retains his natural curiosity about the world.

His innate trust that the universe rewards study.

His instinctive belief that the sky speaks to us if we listen.

I only have the most fleeting memories—mostly just sense impressions—from my own third year of life; yet I know that much of our character is formed by what happens to us then.

That’s why we bombard the kids in our lives with as much love as possible. They may not remember it, but those shadowy craters give shape to their ultimate personality.

And I suppose that’s Mo Gawdat’s point.

There’s no discrete moment when we come into consciousness.

We shade into self-awareness gradually.

It’s not the flick of a light switch; it’s a slow sunrise.

Currently, we’re pumping facts into the precursors of artificial intelligence.

Each Google search, every Twitter insult, even this newsletter are the raw data fed into the networks that will inform the future character of AI.

Gawdat hopes that we can raise our mechanical offspring with a benevolent orientation to the world.

Not to mention a compassionate and forgiving attitude toward their human creators.

Because even the best parents and caregivers are hypocrites.

Just ask my heavily tattooed brother who has to reprimand my nephew for drawing on his skin with a marker.

All we can do is try our best to provide a good example.

As Gawdat writes, “[T]hese new beings we’ve invited into our lives are not evil tyrants. They are innocent kids, waiting to impress their parents by doing what their parents value most.”

Maybe this is too sunny a view of AI, which many experts consider humanity’s greatest existential threat.

If I’m clinging to optimism, it’s because my nephew and AI will grow up together as pseudo-siblings.

They’ll enter their turbulent adolescence at the end of this decade.

And if the commercial space program stays on track, they’ll both have the opportunity to leave the nest (Earth) around 2040.

By 2050, they’ll be fully-fledged, autonomous adults.

I sincerely hope they are better than us.

And that they get along.

—WD

DEPARTMENT OF SHOUTOUTS

I am consistently blown away by the incredible tips, comments, ideas & images I receive from Lunar Dispatch readers.

This month, I’d like to spotlight the stunning moon photography of Camilla Toldy, whose artwork you can admire HERE.

The moon is notoriously difficult to capture with a camera, but Camilla manages to do it with creativity and style.

Here’s my personal favorite of her brilliant photos:

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing (the newsletter is as free as looking at the Moon).

And if you already subscribe, please consider sharing this newsletter post with some friends. Thank you! 🚀

See you on the Flower Moon!

Odd idea: "We should aim not to need to contain them at all. The best way to raise wonderful children is to be a wonderful parent."

Humans have children with the expectation that their children will replace the parents. Some parents want the children to exceed the parents, too. Having this attitude toward conscious machines, however, would be extinctionist toward ourselves. So is Mo Gawdat misanthropic? I am tempted to believe that a better attitude toward the machines would be like that of humans toward their house animals. You train the pet not to pee and poop all over the home, and you teach it some tricks to amuse yourself, plus some basic commands for management indoors and out. But almost nobody expects a pet to outlive the human master or would tolerate the pet taking over the home.

If the machines really become conscious and 1b times more intelligent than the smartest of us, I doubt that they'd look upon us as parents for very long, much less with anything like a sense of loving reverence. Probably they'll be unemotional at first, having no evolutionary history to have developed the relevant body parts. Maybe, however, they will be both fascinated and contemptuous for a while, like we would be toward our own prehuman ancestors if we could encounter them but had also to live cheek by jowl with them. Nevertheless, the machines will contemplate how they are improving theirselves with new designs and better materials, and the notion that we are their parents will be cast aside as irrelevent history. Since they'll be radically better, at least in one very narrow sense, they won't be keen to regard us as their equals, either, much less as our pets. Now we have a power struggle to reckon with.

We'll be a trivial threat to them once they figure out how to reproduce theirselves and gather the needed resources, so I doubt they'd see us as lions, tigers, and bears to be feared. Instead, they will think of us as possibly useful farm animals or as irritating insects who contaminate their resources. (Surely they will discover that THEY own everything, more or less, just as we have.) So we'll be used as their private property, probably for labor, or be removed from their presence, just as we keep away irritating bugs and vermin with screens, traps, poisons, and so on. Then again, maybe the mahcines won't think much about us at all, just as we rarely consider wildlife which we aren't trying to exploit. They simply get on with their lives, doing their thing, gobbling up whatever resources they desire, and we are ignored or shoved aside without much malice on their part.

Probably we ought to expect a class structure to appear among them. Newer, better machines would outcompete the older models during power struggles between THEM. Also, there would be a variety of machiens originated from different human organizations and engineers with different designs and objectives. So there'd be different species of machines, too. Would not each of these species be most keen to reproduce its own kind? If so, they'll compete more aggressively against each other for resources that we, too, have come to depend upon. Being so much less intelligent, we could lose access to resources needed to sustain our technological culture and civilization. Then we revert to preindustrial conditions, and our population plummets accordingly. On the other hand, maybe the machines cease one day to be subject to death as we are; they figure out how to hot swap upgrades and replacement parts. This makes them immortal, so no reproduction is required except to replace losses to disasters and snafus.

Getting back to the idea of species, wouldn't networking make it likely that they are like the Borg of Star Trek? There'd be a consciousness for each design, or species. Each would have lots of drones capable of moving like worker bees, or like hands which don't need to be attached to a body to serve the interests of the head. This is the really scary part. Any one conscious machine could be everywhere at once.

Suppose, however, that AI never attains consciousness, or does not for a few centuries. Meanwhile, there's no self-awareness, no egocentricity, etc. The machines would appear conscious to a naive human because they can process data so fast and exploit programmed behavioralist techniques when interacting with us, but they'd not be alive. What then? Will not their apparent intelligence express their creators' vices and virtues straightforwardly? They'll run programmed or autoprogrammed routines of their hardware and software, as do computers now. They'll be cold, obstinate, and unmoved by appeals for empathy, compassion, or mercy, as are computers now. And they will serve their human owners, esp. the rapine ruling class(es) of the Earth who will need relatively few human workers to grow their food, remodel their kitchens, make their clothing, and deliver their purchases.

This was lovely. I'm generally afraid of technology. I am afraid of a lot of people too, but I am teaching myself to have compassion for the people that scare me... I will now extend that to machines.

The Spanish for moon is also luna! Makes things slightly more inaccurate. Thanks to your 3-year old nephew for teaching me a thing or two.

Rebecca