Dear Lunatics,

I’m writing this newsletter so late that my eyes are slightly bloodshot, which is perfect because the Pink moon is now looking appropriately flushed.

On Monday, you may have seen four astronauts beaming on stage. They have been slated for NASA’s Artemis 2 expedition (a 2024 Moon fly-by), but try as I might, I couldn’t view the event through rose-tinted glasses.

Not only was I conscious of the life-risking mission the astronauts were accepting, but I’ve also begun to worry that the upcoming raft of moon missions—both governmental and commercial—will hamfistedly destroy the Moon’s historical sites.

I’m thinking of the astronaut bootprints and the rover tracks that are already stitched across the Moon’s surface. They have less legal protection than your local duck pond.

This advertisement created by the organization For All Moonkind, which promotes the preservation of human heritage sites on the Moon, says it all:

If you want to see the nightmare scenario that may well await the Moon, look no further than two-and-a-half miles beneath the surface of the North Atlantic.

Dr. Robert Ballard, an underwater archaeologist who discovered the Titanic wreck in 1985, has been distressed by the “circus” of tourists and treasure hunters, some of who have made rogue voyages in mini-submarines to crash like battering rams into the ship’s first-class cargo hold in search of diamonds.

Over five thousand items have been pilfered from the Titanic and its debris field, including shoes, dolls, and crockery. Tourists, who can now pay $40,000 to visit the Titanic in a submersible, have left beer bottles and, in one case, an urn of human ashes. One New York couple exchanged wedding vows on the ship's fragile deck.

Aside from the pirates, two main tribes are currently battling over the Titanic’s rotting corpse: the conservationists and the protectionists.

The conservationists are determined to recover and preserve artifacts for posterity, while the protectionists believe that the wreck is essentially a tomb and any disturbance is akin to grave robbing.

According to the protectionists, efforts to salvage items from the Titanic often cause irreparable damage.

I think they have a point.

In recent years, the ship's crow's nest disintegrated when a team retrieved the Titanic’s warning bell.

The collapse of the crow’s nest was like the tipping of a tombstone. It wasn’t just a barnacle-encrusted platform; it had its own gloomy sacredness.

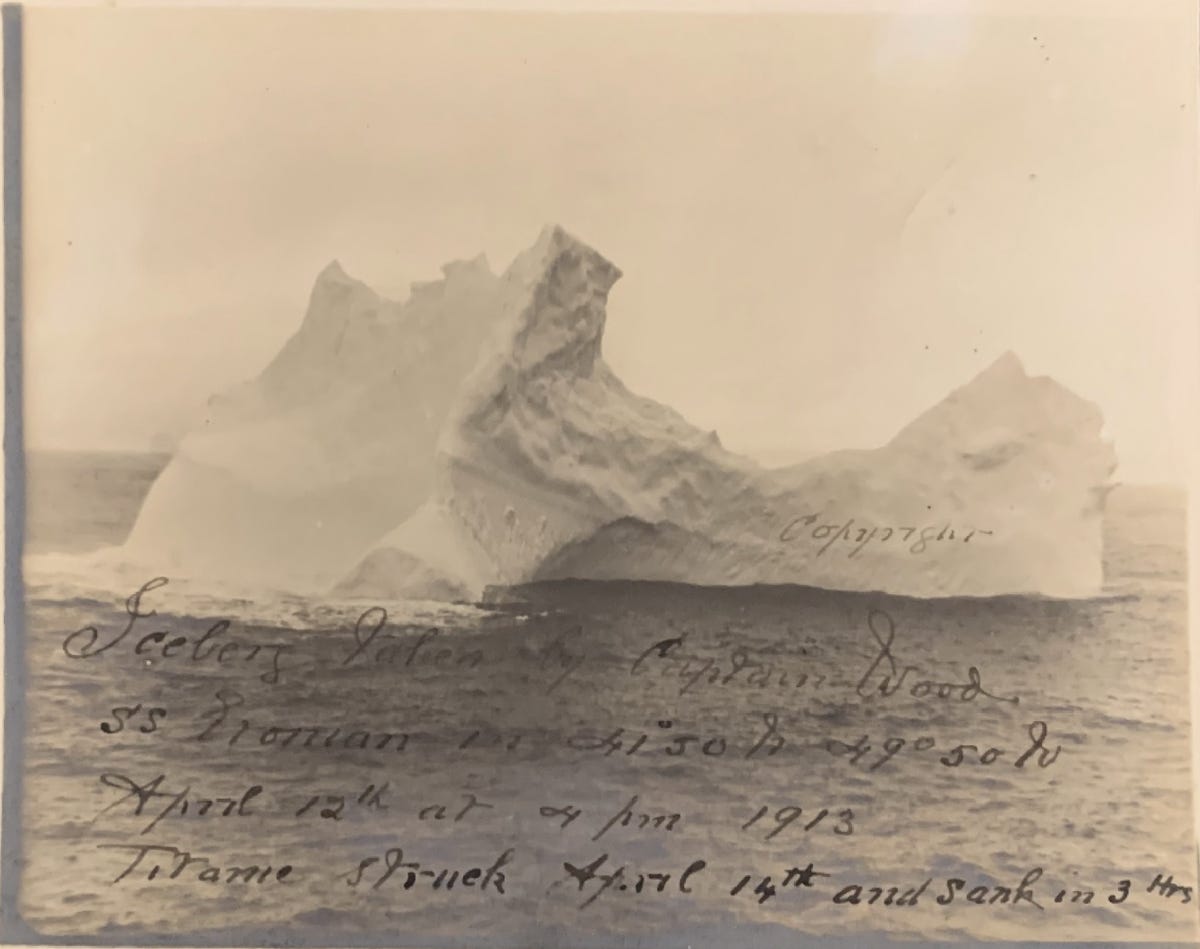

It was on that crow’s nest that the lookout Frederick Fleet, shivering with his companion Reginald Lee, spotted a black haze in the distance at 11:39 PM on April 14, 1912. Fleet rang the bell and shouted those immortal words: "Iceberg right ahead."

To this day, there are questions regarding Fleet’s reaction time. How long did he and Lee discuss the indistinct dark shape before sounding the alarm?

As it turns out, Fleet gave the first officer just enough time to turn the Titanic “hard-a-starboard,” which caused the iceberg to gash the ship’s side. Had Fleet given a faster warning, the iceberg could have been avoided. And if he had said nothing, the Titanic would have rammed the iceberg head-on, damaging the bow severely but allowing the ship to stay afloat.

The two look-outs were forever haunted by their experience. Lee drank himself to death in 1913. Fleet struggled to sleep at night, plagued by visions of the iceberg—that "black thing," as he called it, looming on the horizon. He ended his days selling newspapers on the street. He sought work as a ship’s night watchman, but sailors—that superstitious breed—were weary of his cursed history.

If they only knew what we now know about what really sank the Titanic.

It was the Moon.

A few months before the wreck, the Moon made an abnormally close pass by the Earth, a near brush that we hadn’t seen since 796, nor will we again until 2257. Along with a spring tide, this lunar escapade likely sent a flotilla of icebergs, snapped off from the fjords of Greenland, southward into the Titanic’s path.

But neither Reginald Lee nor Frederick Fleet knew this.

In his 1965 suicide note, Fleet lamented, “Another Titanic man gone.”

I was almost a “Titanic man” myself—or so the family story goes.

With a job as a domestic servant lined up in Boston, my 19-year-old Irish great-grandmother Norah Spillane bought a third-class ticket for the Titanic.

Leaving from Queenstown (now Cork), she was due to sail across the Atlantic in a crammed, pink-floored cabin on the stern’s lower deck, which would have shuddered and clanked due to its proximity to the engines.

During the voyage, Norah would have vied with 700 other steerage passengers for the use of 2 baths. And during the sinking, she would have vied with the same number for a spot on a lifeboat.

Only 174 third-class passengers survived.

The Moon-guided iceberg would very likely have sunk Norah, and therefore me, and therefore this newsletter had it not been for Norah’s mother, Margaret, who held to an old superstition that only cattle and lumber should ride on a ship’s first voyage.

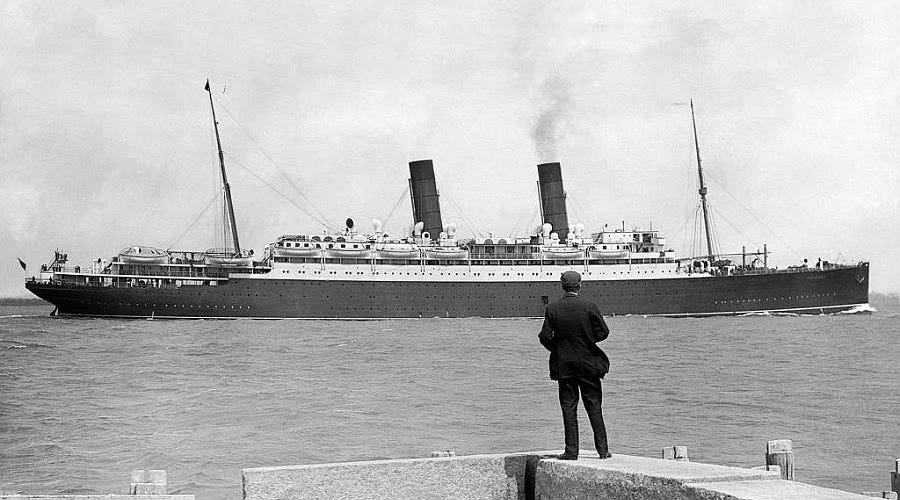

Margaret demanded that her daughter turn in her Titanic ticket and sail aboard the RMS Franconia, which she grudgingly did, arriving in Boston on April 12th.

Norah never saw Margaret again (she couldn’t afford a trip home on a maid’s salary) and she always regretted that her final meeting with her mother had been marred by a fight over ticket prices and what had seemed to Norah to be an old wives’ tale about maiden voyages.

For a long time, I thought this story about my great-grandmother and her forfeited Titanic ticket was itself an old wives’ tale. The whole scenario seemed implausible.

But then I consulted Senan Molony’s The Irish Aboard Titanic and found a nearly identical story.

Jeremiah Burke was a 19-year-old farmer’s son from Ballynoe. Like Norah, he bought a third-class ticket on the Titanic intending to find work in Boston. And like Margaret, Jeremiah’s mother was worried.

The morning Jeremiah departed for Queenstown to board the Titanic, there was no knock-down-drag-out fight.

His mother did not throw herself in front of the pony and trap that was carrying him away.

She simply pressed a bottle of holy water into his hands for good luck.

Three-and-a-half days later, Jeremiah Burke was in the Atlantic.

His body was never recovered.

Soon, the salvage firm RMS Titanic, Inc. will send an expedition team to cut through the Titanic’s hull and retrieve the most famous radio in the world.

Preserved in the so-called “silent room,” the Marconi wireless telegraph was used to send the sinking ship’s distress calls.

These Morse code messages (“We require immediate assistance”; “Have struck iceberg and sinking”; “We are putting women off in boats”) reached the RMS Carpathia, which arrived two hours later to scoop up hundreds of survivors (and frozen bodies).

Given the pivotal role his radio played in the rescue, Marconi became a hero after the disaster. Bizarrely, Marconi himself was nearly onboard. The inventor and his family had been offered free tickets on the Titanic but he opted to ride the Lusitania instead because he had a large stack of business correspondence to get through and the Lusitania employed a superb stenographer. Marconi’s wife Beatrice and their children were still Titanic-bound, but then their youngest son Guilio came down with a fever, necessitating a life-saving change of plans.

The unsinkable Marconi survived for another half-century, only dying after his ninth heart attack. At the time of his death, Marconi had been laboring in secret on two mysterious devices.

The first was a phantom death ray that could be used to slice enemy vessels in half—who needs icebergs?

The second was a radio so sensitive it would be capable of recapturing the far-rippling sound waves of every word ever spoken in human history.

Personally, I find the second never-completed invention to be the more terrifying.

The idea that all my utterances—from my first baby coo to the curse I let out five minutes ago when my computer froze—could be retrieved and played back, as though I’d unwittingly spent my whole life in the company of a superb stenographer, makes my blood run ice cold.

I can’t even bear to listen to my voice on an answering machine.

Of course, the Titanic-obsessive in me understands the temptation. With Marconi’s apparatus, we could finally hear, muttered between cigar puffs, that backroom deal about cheap rivets that reportedly contributed to the ship’s rapid submersion. And we could overhear the whispered conversation in that crow’s nest. Like silver cutlery dredged from the ocean floor, secrets taken to the grave would be brought to the surface and we would know, finally, definitively, who was to blame.

But who wants to eavesdrop on the rest of it?

The rushed goodbyes of families separating on deck.

Then all those prayers murmured between chattering teeth.

And the Titanic is just one tragedy. Marconi’s device would be the black box pulled from the wreck that is human history. Every shriek of our colicky species would come back to us. All the battle cries. All the family blowouts. Taken orchestrally, they would sound like nothing more than one desperate SOS wailed into the night.

Marconi, who was a devout Catholic (death ray notwithstanding), had one major ambition for his invention.

He was hoping, above all, to hear the last words uttered by Jesus on the cross.

When it comes to human speech, are you a conservationist or a protectionist?

Should we preserve our words for posterity? Or should we leave our acoustic vibrations be, letting them drift like “black things” through the dark ocean of space?

I’m torn.

If we manage to assemble Marconi’s all-hearing radio, could we justify tuning into the North Atlantic on April 15th, 1912? Aside from satisfying our morbid curiosity and settling bets between professional historians, what good could come from listening to the last words of people too late to save?

But then I think of Jeremiah Burke and his mother, the one who pressed that bottle of holy water into the hand of her departing son.

I think of her a year after the tragedy, dying of cancer while mourning her lost child, the pain of his absence cutting her in half like a death ray.

With no body to bury, the ocean was the closest thing Jeremiah Burke had to a grave.

Did his mother visit the nearby shore?

Or did she shun the sight of the sea?

One morning, in the summer of 1913, a postman walking his dog on a shingle beach in Cork Harbour came across a bottle glinting among the pink rocks.

Inside was a note scrawled in pencil:

“From Titanic

Good Bye all

Burke of Glanmire Cork”

Jeremiah’s goodbye, which he had apparently scribbled and tossed into the sea from the listing deck of the sinking Titanic, was promptly delivered to his mother.

She kept it close for the remaining months of her life.

I know what you’re thinking—there’s no way this note was genuine. What are the chances that Jeremiah’s message, after a year bobbing at sea, would wash up on the shoreline just a few miles from his home?

But the note was genuine.

His mother recognized Jeremiah’s handwriting as well as the shoelace he used to tie the letter up.

But more than that, she recognized the bottle it came in.

The holy water was gone, of course, and in its place were her son’s final words.

Let’s not be too hard on the Moon.

It may have shoved the iceberg into the path of the Titanic, but it also persuaded the currents to carry Jeremiah Burke’s words over 2,000 miles of open ocean, perfectly preserved, all the way home.

See you on the Flower Moon!

—WD

If you enjoyed this post, please subscribe to this monthly newsletter for free here:

Also, please consider sharing this post with some of your fellow Earthlings 🚀.

P.S. A quick Substackian shoutout: Today, I became a paid subscriber to Madeleine Dore'sOn Things. Dore, who is the author of I Didn’t Do The Thing Today, is a thoughtful, curious writer with a keen nose for synchronicity. I always appreciate her insightful comments about the LD, and I really enjoy her newsletter. If you’re not already familiar with her writing, check it out.

Oh, I loved this piece. What tales. What tragedy. Thank you for sharing.

Always a delight to watch the moon (and its mischief) from your eyes. That story - how the moon moved the handwritten note, which was found by a postman, in a bottle given by his mother - is so pure. Thank you. <3