SNOW MICROMOON 2024

Suits and Ladders

Dear Lunatics,

Bad news: the moon landing has been pushed back to 2027.

Part of the holdup is the seemingly never-ending process of crafting new spacesuits, for which NASA has dedicated $3.5 billion.

What’s wrong with the Apollo suits? They got the job done, right?

Apparently, they were absurdly dangerous, cobbled together with rubber joints, metal cables, and a crotch-to-shoulder zipper that could easily burst. They were also heavy. According to one French astronaut, wearing the spacesuit “felt like being in a coffin with a window.”

Lindsey Aitchison, a NASA Space Suit Engineer, cringes at the Apollo footage. The old suits look clunky, she says, “like your astronauts are not particularly graceful.”

Recently, it was announced that Axiom Space would collaborate with Prada to create a more flexible, not to mention stylish, spacesuit.

Axiom’s voguishly black prototype was dramatically unveiled last March.

Of course, like most fashion modeling, the clothes are just for show.

When the Artemis astronauts climb gracefully down the ladder to the lunar surface in 2027, the sleek dark layer will be exchanged for a traditional white layer with red lining since white reflects the extreme heat from the Sun instead of absorbing it.

This reminds me of my favorite three lines of poetry written by Charles Simic:

Happiness, you are the bright red lining

Of the dark winter coat

Grief wears inside out.

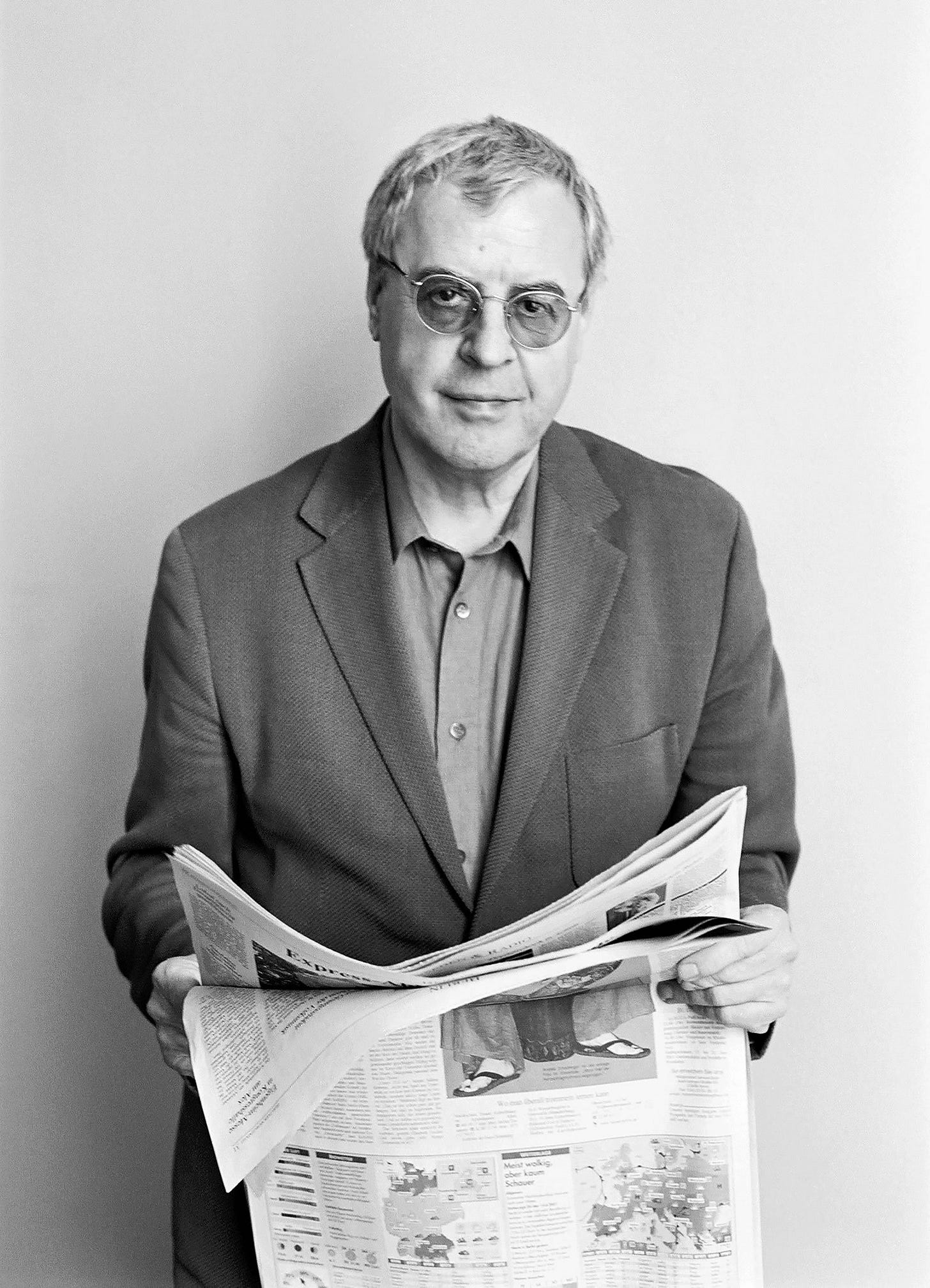

I once had the opportunity, while taking a workshop, to visit Charles Simic during his office hours and find out what he thought about a poem I had submitted.

While I waited, pacing outside his office, I couldn’t help but overhear his meeting with the student before me.

“Where is it?” he grumbled, rustling the papers on his desk, evidently looking for the student’s poem.

Then, from the hallway, I watched as he started to dig through his trash bin, pulling out a half-eaten pear, a coffee filter, a leaky pen, and, finally, a crumpled piece of paper that he smoothed across his knee and began to read through his dark glasses.

I bolted.

I couldn’t bear to see my precious poem fished out of that trash bin like a used napkin. Simic was my idol and I was simply too thin-skinned.

Maybe if I had been wearing a fully pressurized spacesuit…

There’s a good reason we don’t require spacesuits in daily life—Earth is our spacesuit.

“The planet’s magnetic field helps preserve the ozone layer, which in turn shields us from dangerous ultraviolet radiation; a thick atmosphere burns up most incoming rocks; and natural processes generate the air we breathe,” Mark Harris wrote for Smithsonian Magazine.

However, there are some people so sensitive that they find even the ideally-suited conditions of Earth as harrowing as outer space.

We call them poets.

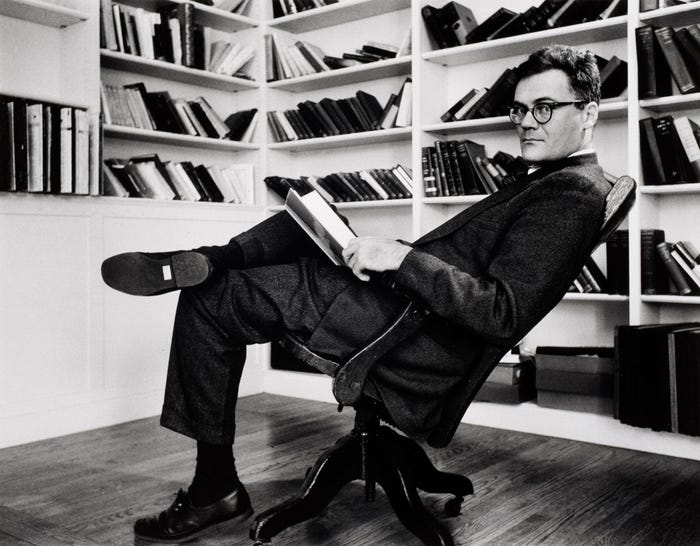

If I could attend one poetry workshop in history, it would be the one that took place at Boston University in 1959. The teacher was Robert Lowell and among the students were two stars: Anne Sexton and Sylvia Plath.

All three would become major poets, and all three would suffer bouts of serious mental illness.

At least in their poetry, they blamed this last misfortune on the Moon:

Lowell dubbed the Moon a “lunatic's pill with poisonous side effects,” a “strange white goddess” who causes hallucinations.

Plath thought the Moon’s “O-mouth” was a frozen expression of despair and grief. “I live there,” she wrote.

And as for Sexton, the Moon “under its dark hood / falls out of the sky each night, / with its hungry red mouth / to suck at my scars.”

After the workshop ened, the three poets graduated, in a way, to an even more prestigious wellspring of 20th-century poetry:

McLean psychiatric hospital.

Founded in 1811, McLean was a renowned sanatorium for Boston’s artists and cognoscenti. Alumni include the musicians Ray Charles, James Taylor, and Steven Tyler and the writers David Foster Wallace, Susanna Kaysen, and Mary Karr.

Plath was only admitted to McLean once, for several months during her senior year at Smith College, an experience she mined for her classic novel The Bell Jar.

But Lowell was a McLean regular with four extended stays over eight years. He was already famous when he arrived—a Pulitzer Prize-winning poet and a Boston Brahmin whose illustrious family tree included the astronomer Percival Lowell (hence the “Lowell crater” on the Moon).

Lowell may have been in the grip of manic grandiosity while at McLean, insisting he was Jesus and Napoleon, but he was also receiving letters from the likes of Jackie Kennedy, who commended him on getting away for the holidays.

Patients and staff alike would sit at Lowell’s feet as the brilliant poet delivered extemporaneous lectures in his nasal voice on a seemingly endless number of subjects.

One of his audience members was a mathematician who had been involuntarily committed after becoming convinced that anyone walking around Boston in a red necktie was part of a crypto-communist conspiracy against him.

Despite holding fast to his delusions, the mathematician managed to get released within 50 days. He quickly learned the rules of the hospital and determined how to fool the doctors who were, as far as he was concerned, imprisoning him. This was quite a feat for John Nash, whose paranoia was famously depicted in the film A Beautiful Mind as a garage full of newspaper clippings connected by a web of red string.

Then again, maybe we shouldn’t be too surprised that Nash found a strategy to escape a psych ward. After all, he would eventually win a Nobel Prize for his contributions to Game Theory.

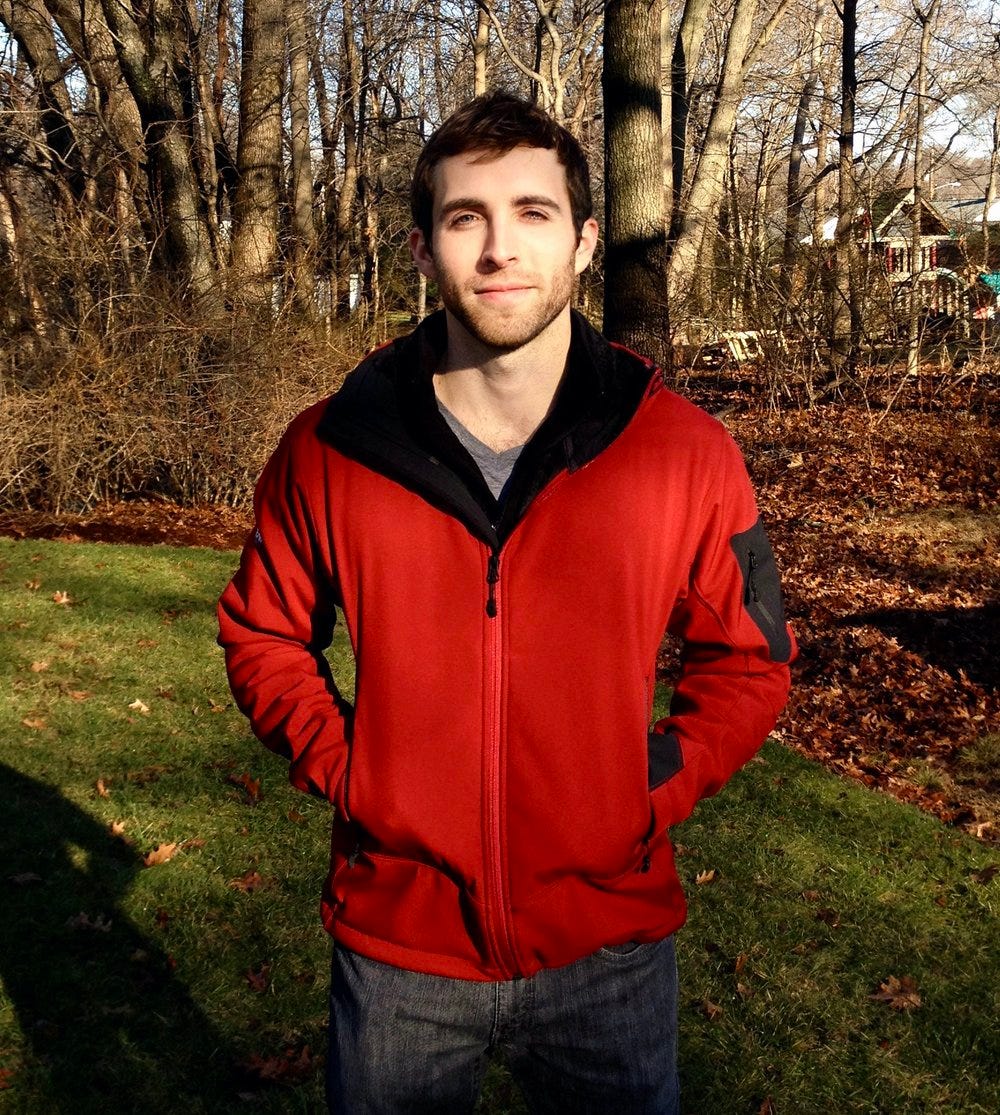

By the way, if you’re wondering whether I, as a Boston area poet, had my own McLean rite of passage, the answer is…sort of.

About a decade ago, in between surgeries and nearly out of my mind with pain, I attended a day program at a different Boston hospital.

Terrified of being locked up, I was determined to make it clear from the start that I wasn’t crazy crazy—just driven slightly mad by physical agony.

As soon as I arrived at the hospital, odd things began to happen. Someone tossed me their car keys as I walked through the revolving door. On the elevator, a nurse told me everything she’d done that weekend in extraordinary detail. All day, I was late for my sessions because receptionists kept asking me to pass messages to departments in distant wings of the hospital. I didn’t get a bite to eat at lunch because a janitor made me mop up someone else’s spilled fruit juice. When the program ended, I was pressed into service wheeling clinical waste bins down to the loading dock.

By the time I got out of there, it was dark. I remember sitting in my car, looking up at the winter moon, and thinking: it’s finally happened, I’ve gone crackers.

It wasn’t until the second day that I noticed the hospital’s workers were all wearing the same red jackets.

Guess who else had been wearing a red jacket?

With Plath and Lowell institutionalized, Anne Sexton felt left out. "I want a scholarship to McLean," she once told to a friend.

In 1968, she finally made it in—as the leader of a poetry workshop for the patients.

Sexton fretted over how to critique the work of participants. How could she take a red marker to a poem and then hand it back to a poet who has red marks up and down their arms?

'What if I say something about a poem that sends them over the edge?"

Yet she managed, and some of Sexton’s students exhibited huge talent, some of them going on to publish collections.

As a teacher at McLean, Sexton stood out. She was an ex-fashion model and was sometimes mistaken for an actress.

But five years later, when she was admitted to the hospital as a psychiatric patient herself, one of her former students passed her in the hallway and was struck by how awful she looked. “My heart went out to her,” the student later said.

“Here was the terrible leveling of mental illness; Sexton, the elegant, chain-smoking, Pulitzer Prize winner cast adrift among her student-patients on the desperate ocean of unhappiness,” Alex Beam wrote in his excellent history of McLean.

Life on the Moon will be another great leveler.

Why spend millions of dollars to make spacesuits haute couture?

When the Artemis team is trudging across the inhospitable moonscape in temperatures that swing from -373°F to 250°F, I doubt they’ll be scrutinizing the label on their fellow astronaut’s boots to see if they’re Prada knockoffs.

Lowell, who knew something about wild swings, would’ve killed for a helmet to insulate his mental state, no matter how bulky or off-trend its design.

While teaching his famous Boston workshop, Lowell often vanished for stays in McLean. Sexton thought his discreet disappearances were chic. “I must admire your skill,” she wrote fawningly. “You are so gracefully insane.”

But for Lowell, there was nothing graceful about descending from his manic episodes. He would step awkwardly through the debris of his upended life and reach into the torn, messy heaps of writing he produced in the white heat of psychosis to find poems worth salvaging.

Lowell once described the feeling of returning to sanity in a letter to his friend Elizabeth Bishop: “Gracelessly, like a standing child trying to sit down, like a cat or a coon coming down a tree, I’m getting down my ladder to the moon. I am part of my family again.”

Despite suffering practically annual breakdowns for thirty years, Lowell did not kill himself, unlike his two students. He died sprawled in the back seat of a New York taxi, the victim of a heart attack.

His final lines of poetry, which he scribbled just days before death, were read at his memorial:

Christ

May I die at night

With a semblance of my senses

Like the full moon that fails.

Lowell got what he wanted. He died sane. And on the new moon, no less.

Tonight, of course, is the full moon.

The Snow Moon.

Charles Simic once compared the moon to a nightwatchman that “check[s] with its lantern / On every last patch of snow / That may be hiding in the woods.”

The book in which these lines appear is titled The Lunatic.

It was one of Simic’s last books.

He died last winter.

Now I’ll never know what he might have said to me that day I fled from his office threshold.

In a way, life is like the night sky.

It drops ladders of woven light into our path, and it’s up to you whether to grab ahold and climb or brush them away like cobwebs.

Do these ladders lead to madness or grace, to the Moon or the locked ward?

Who can say?

But if you do climb, just know, there may be no coming back.

And you can’t bring a jacket.

***

See you on the Worm Moon!

—WD

Thank you for accompanying me in my lunacy with this newsletter.

From one poet to another --

Rebecca

As I drove south on the Taconic Parkway last night, I saw to my left the full moon and my first thought was there’s a new Lunar Dispatch awaiting me when I get home. My second thought: such a beautiful, bright moon, I almost don’t need to use my headlights.