Snow Moon 2022

A Study in Silver

Dear Lunatics,

This weekend, while working on a story, I paused for half an hour to plot out moon phases. Most fiction writers handle the moon like a careless gaffer, and I was determined to show our nearest celestial body more respect.

At least the detective novelist Alan Bradley had the courtesy to include the following postscript to one of his books:

In order to provide sufficiently dramatic lighting for this story, I must admit to having tinkered slightly here and there with the phases of the moon, though the reader may rest assured that, having finished, I’ve put everything back exactly as it was.

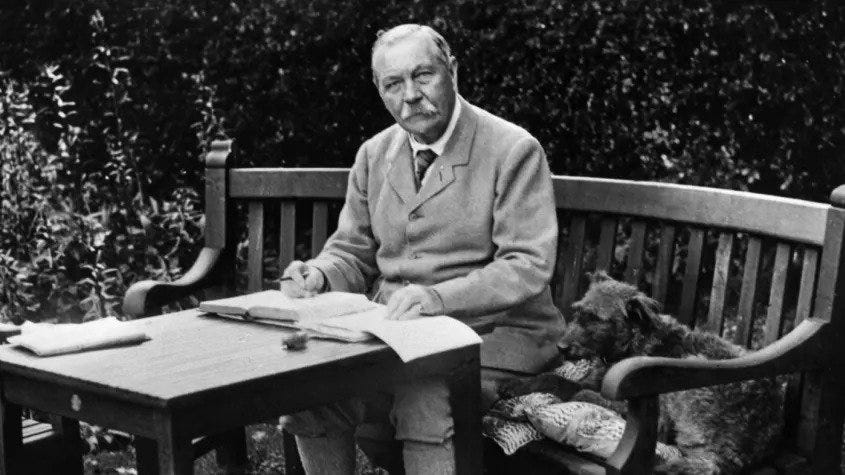

Arthur Conan Doyle, meanwhile, was not so conscientious.

In The Hound of the Baskervilles, the moon rises and sets on an impossible schedule. One night, it appears as a waxing gibbous; the next night, it recedes to a half-moon.

It’s enough to make any moon-watcher pull their hair out.

Conan Doyle equipped his master creation, Sherlock Holmes, with encyclopedic expertise—chemistry, anatomy, geology, botany. But Sherlock was famously oblivious to the workings of the Solar System.

When Watson informs him of the Copernican Theory, here’s how Sherlock responds:

"What the deuce is it to me?" he interrupted impatiently; "you say that we go round the sun. If we went round the moon it would not make a pennyworth of difference to me or to my work."

Sherlock’s astronomical ignorance has always been interpreted as a delightful character quirk—the myopia of an eccentric genius.

But I make a different deduction.

I’m convinced that Conan Doyle made Sherlock unconcerned with the heavens so the detective wouldn’t notice when the moon behaved bizarrely. This way the protagonist of four novels and 56 short stories wouldn’t come to the horrible realization that he was living inside a fictional world.

If you think about it, the only way you would become aware of the world’s artificiality would be by noticing a glaring error.

This is not a new concept.

In a 1977 speech, the science fiction author Philip K. Dick confidently announced:

We are living in a computer-programmed reality, and the only clue we have to it is when some variable is changed, and some alteration in our reality occurs.

These changed variables have come to be called The Mandela Effect.

Hundreds of people have vivid memories of Nelson Mandela dying in prison in the 1980s. They remember where they were when they heard the news, and they even recall specific features of his funeral.

There are many internet sites that catalog these collective false memories of alternate history.

Examples include:

In Snow White, the Wicked Queen says “Magic mirror on the wall,” not “Mirror mirror on the wall” as many of us recall.

The line “Play it again, Sam!” is never uttered in the film Casablanca.

That caveman cartoon from your childhood was called The Flintstones, not The Flinstones.

During the Apollo 13 mission, the astronaut Jack Swigert radioed “Ah, Houston, we’ve had a problem”—not “Houston, we have a problem.”

While Neil Armstrong is remembered for saying “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind,” that’s not how he remembered it. Armstrong insisted that he actually said, “That’s one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind.”

The idea that we might be living inside a computer simulation has been steadily gaining traction in the scientific community. In 2020, Columbia University astronomer David Kipping put the odds at 50/50.

Recently, I’ve been reading The Simulation Hypothesis: An MIT Computer Scientist Shows Why AI, Quantum Physics and Eastern Mystics All Agree We Are In a Video Game. The author, Rizwan Virk, who has designed multiplayer online video games, sees parallels between these virtual worlds and the Buddhist vision of existence:

…Eastern religious traditions teach us that we are either soul or consciousness that gets downloaded into a physical body for the duration of the dreamlike state, which we call life. This happens multiple times, and we end up with multiple lives, not unlike what happens in video games.

Karma is, in fact, like an endless quest engine in video games, keeping track of our achievements and our goals, and creating situations with other players that we need in order to resolve previous karma.

Imagine what heinous crimes Sherlock Holmes must have committed in a previous life to spend this incarnation thwarting an endless procession of murderers and thieves.

Even the author got worn out after a while.

By 1893, Conan Doyle was sick to death of his famous detective:

I have had such an overdose of him that I feel towards him as I do towards paté de foie gras, of which I once ate too much, so that the name of it gives me a sickly feeling to this day.

So in “The Final Problem,” the author flicked Sherlock Holmes over the Reichenbach Falls along with his archnemesis Professor Moriarty. “Killed Holmes,” Conan Doyle wrote in his diary.

![Sherlock Holmes and Professor Moriarty at the Reichenbach Falls. Ilustration by Sidney Paget to the Sherlock Holmes story The Final Problem by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle [1], which appeared in The Strand Magazine in December, 1893. Sherlock Holmes and Professor Moriarty at the Reichenbach Falls. Ilustration by Sidney Paget to the Sherlock Holmes story The Final Problem by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle [1], which appeared in The Strand Magazine in December, 1893.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!NUWv!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F8aa6d311-613f-4a97-86ce-5422b7fb6fa9_800x1245.jpeg)

The English, known for their stiff upper lip, did not take the death of Sherlock Holmes well.

Twenty-thousand readers immediately canceled their subscription to The Strand Magazine, while young men across London expressed their state of mourning by wearing black armbands for a month.

For nearly a decade, Conan Doyle faced widespread pressure to bring his beloved character back from the dead.

But he refused to give in.

“I have been much blamed for doing [Holmes] to death,” Conan Doyle said, “but I hold that it was not murder, but justifiable homicide in self-defense, since, if I had not killed him, he would certainly have killed me.”

But in 1903, Conan Doyle changed his mind.

What convinced him to dredge Sherlock from his watery grave?

The publisher of the American magazine Collier’s offered Conan Doyle $45,000 (or about $1.5 million today) for a new Holmes story.

I wonder what went through Sherlock’s mind when he found himself at the beginning of a new tale after his dramatic demise.

Did he actually buy his own retconned survival story? Was he even glad to be resurrected? To reappear like Pac-Man inside another labyrinth with more cloaked criminals needing to be pursued and gobbled up by his rapacious intellect?

After considering Sherlock’s strange literary life (and afterlife), I can’t decide which scenario is more dystopian:

That we entered this video game of existence voluntarily, perhaps by slotting a quarter in some interdimensional arcade, knowing that we’d experience temporary amnesia and all the joys and pangs of an indeterminate human lifespan?

Or that we were shoved unceremoniously into this world of suffering and striving by a ruthless creator who was merely capitulating to the demands of a capricious audience of whom we can’t possibly conceive?

Growing up, I wanted to become Sherlock Holmes.

Deerstalker hat and all.

But instead, I became his opposite.

Sherlock spent his career looking down, peering through a magnifying glass at muddy footprints and bloodstained carpets, forever searching for a link in the world’s epic chain of cause and effect.

I spend my career (such as it is) looking up, peering through binoculars at the moon’s cratered visage, forever searching for shimmering inconsistencies, misprints in the world’s coded text.

Maybe tonight, in defiance of astronomical laws, the moon won’t be full, but rather darkly shaded on one edge as it wearing a black armband.

Maybe I’ll even catch the Man in the Moon yawning for a second.

Sherlock looked for the clues; I look for glitches.

But on one thing, the great detective and I are in agreement.

The game is afoot.

—WD

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing (the newsletter is as free as looking at the Moon).

And if you already subscribe, please consider sharing this newsletter post with some friends. Thank you! 🚀

See you on the Worm Moon!

As usual, I love what you've written here...

Great writing! This was a nice morning read. Thanks!