Dear Lunatics,

If the dismal housing market has you considering a move to the Moon, there are some things a lunar realtor may neglect to mention but you should probably know.

While there’s plenty of acreage to be had, there’s no breathable air on the Moon. Temperatures fluctuate between 250° during the day to -200° during the nighttime, which, incidentally, lasts two weeks. That powdery lunar dust is actually as sharp as glass. And did I mention solar storms, cosmic radiation, hour-long moonquakes, and a hail of micrometeorites?

As the headline of one article recently put it, “Trust Me, Living on the Moon Will Be Hell.”

So naturally, the U.S. government is pouring immense resources into establishing a permanent lunar colony. Just two weeks ago, NASA awarded contracts to companies to carve roads, lay high-voltage power lines, and, most importantly, build houses on the Moon’s South Pole.

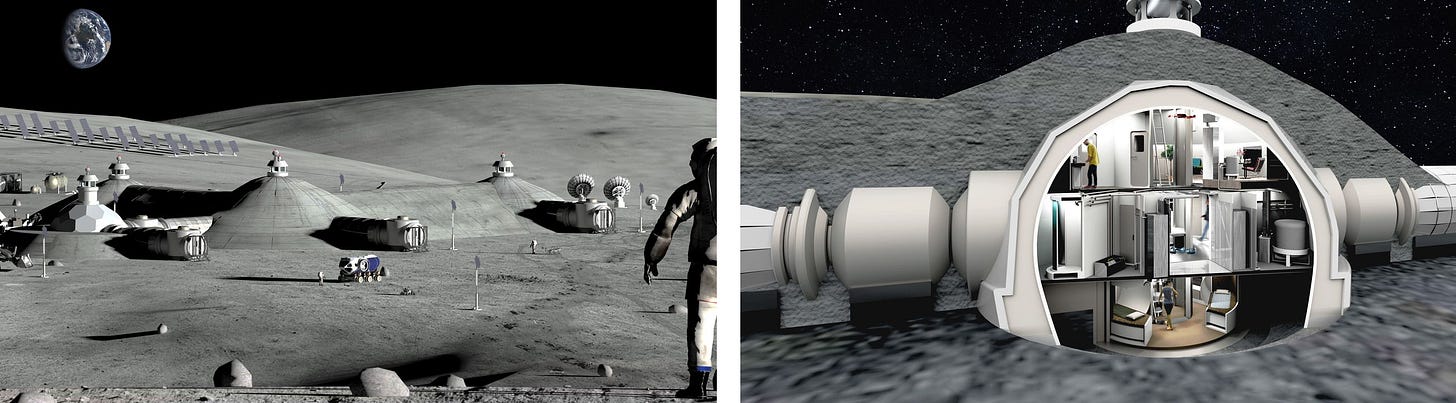

So what exactly would a home on the Moon look like?

In 2021, the UK house-building company Barratt decided to find out.

The company asked Mark Hempsell, a British aerospace engineer and former President of the British Interplanetary Society, to help design a domicile for lunar residents—and he agreed.

“It sounded like fun,” he told me when we spoke.

Hempsell’s first innovation was to reverse the typical floor plan on Earth. Bedrooms on the Moon will be situated on the bottom floor in order to provide an extra level of radiation protection as we sleep.

While models of other lunar homes boast interiors that look like Swedish saunas, Hempsell reduced the number of wooden fixtures. (Imported wood would be incredibly expensive on the Moon—just think of the shipping fees.) Instead, he imagines furniture would be fashioned from metals and other materials derived from the lunar soil itself. If a metal kitchen table sounds less than cozy, at least it’s fireproof.

According to Hempsell, the inside and outside of lunar homes would be largely made from the cheapest, most ubiquitous material available—moon rocks.

The walls? Basalt bricks with steel tube reinforcement.

The roof? Like a two-meter-deep swimming pool filled in with radiation-absorbing regolith.

And insulation? Hempsell has suggested using lunar sandbags.

Listening to Hempsell speak, I was reminded of another frugal homebuilder: Henry David Thoreau.

As most American high schoolers will groaningly recall, Thoreau devotes several pages in Walden to the meticulous description of the materials he used to build his cabin. Aside from the brick chimney, the iron nails, and the borrowed ax, Thoreau relied almost entirely on wood.

Trees were essential to Thoreau, not only in his capacity as a naturalist but also as the raw material of his two primary professions—writer and pencil maker. Not many people know that Thoreau invented the best-known pencil in the United States at the time. Before he came along, pencil makers cut the wood cylinders in half, inserted the graphite, then glued the two pieces back together. Thoreau’s innovation was to drill a hole and pour the graphite inside, which seems obvious now but inventions always do in hindsight.

(There’s an apocryphal legend that during the space race, NASA spent millions of taxpayer dollars developing an anti-gravity pen that could still write when our astronauts were floating upside down, while the Soviets simply gave their cosmonauts pencils.)

In Walden, Thoreau also gives the exact dimensions of his self-erected cabin: 10 feet by 15 feet.

These are almost the identical dimensions of the Orion crew module that will carry four Artemis II astronauts on a trip around the Moon next year.

They also happened to be, to the inch, the dimensions of my bedroom, where I’ve been cooped up due to a long illness.

While neither the astronauts nor I could leave our tight quarters, Thoreau could and frequently did. He visited the village nearly every day and stopped by his parents’ boarding house for a home-cooked meal and—infamously—to have his few shabby shirts cleaned.

This detail—Thoreau’s Mom did his laundry—has become the schoolyard taunt used to drown out everything Thoreau wrote in Walden.

I always bristle at this line of attack.

Not just because the annual Tweet storms are brewed by people typing away on their phones while bored at the laundry mat, living lives of technological luxury that would be unimaginable to even the wealthiest 19th-century American. And not even because the knock against Thoreau is almost certainly untrue (see Mysteries of Thoreau, Unsolved, by Rebecca Solnit).

I bristle because my own mother does my laundry.

For several years now, I haven’t been able to lift the basket, so she does it for me.

I could manage the feat on my own—if I lived on the Moon.

The Moon has 1/6th of Earth’s gravity, which is why the blueprints to lunar homes often show ladder rungs and stair treads a full yard apart.

In a Moon house, not only would the bulkiest laundry basket be easy to lift, but you’d discover a surprising spring in your step.

I wonder if, in the future, Earth’s launch pads will be littered with discarded canes and walkers as the elderly and disabled set off for greener (and grayer) pastures.

I’m fascinated by the proposed staircases in lunar dwellings.

Every design seems to include a central, vertical stair column that connects all levels.

It’s the type of architectural oddity that on Earth you only encounter in firehouses and some attic apartments, where the stairwell opens perilously in the middle of the room.

After his two-year sojourn in the woods, Thoreau moved into just such an attic, where he would spend years revising his manuscript until finally, in the summer of 1854, Walden was published.

Instead of triumph, Thoreau felt bereft. The book sold dismally and he had no idea what to write next. Worse, the summer of 1854 in New England was much like the summer of 2023 in New England: boilingly hot with an apocalyptic haze of smoke from forest fires.

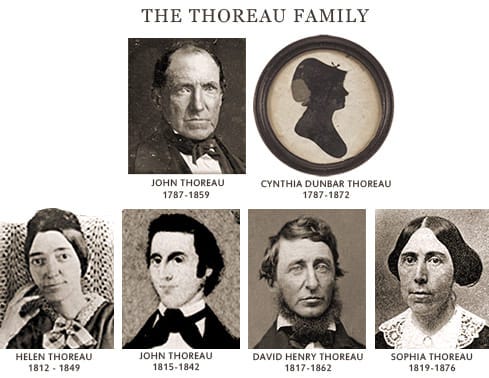

During the heatwave, Thoreau’s attic became too stuffy at night for him to stand. He wasn’t being overly fussy. For twenty years, Thoreau had been struggling with symptoms of tuberculosis, the disease that would eventually kill him at age 44. In fact, over the years, tuberculosis had rained down like a meteor shower on the whole Thoreau family, wiping out the writer’s grandfather, father, sister Helen, and brother John, whose demise was particularly traumatic.

John Thoreau nicked his finger while shaving and died after eleven days of excruciating body spasms. Thoreau, who nursed John through the entire ordeal, subsequently developed all the same symptoms, his own body wracked with involuntary convulsions. He spent a month confined to his bedroom before slowly recovering. The doctor never found a sign of infection to explain the episode, and Thoreau’s mysterious illness was deemed “sympathetic.”

So, to fill his lungs with fresh air, Thoreau would quit his stifling garret and go out walking at night. And it was during these walks that he found his new subject: moonlight.

He noticed how the summer Moon, which he’d only occasionally glimpsed through his shutters, polished the surfaces of Concord to a “bright, pale, whitish lustre.”

Moonlight, he realized, was a foreign language that he’d never bothered to pick up.

What messages had he missed?

“What if one moon has come and gone with its world of poetry, its weird teachings, its oracular suggestions,—so divine a creature freighted with hints for me, and I have not used her?”

From then on, Thoreau resolved to spend his nights wandering outdoors, studying the “mysterious, silvery, poetic light,” even if he “should sleep all the next day to pay for it.”

I discovered this same reverence for light in another designer of lunar residences.

When Takaharu Igarashi, a Ph.D. candidate at Purdue’s School of Aeronautics and Astronautics, was tapped by the Resilient Extraterrestrial Habitat Institute to model Moon homes that would be mostly buried under the lunar surface, his first thought was of light.

“Whether Buddhist temples or Christian churches, many religious buildings on Earth are intentional about how they introduce light into the room,” Igarashi told me when we spoke.

That’s why he added cupolas to the top of each abode. These above-ground turrets would give the inhabitants a much-needed break from feeling entombed underground and allow celestial light to pour down into the dome.

They would also offer a panoramic vista of the Moon’s surface.

We’ve all seen pictures of a moonscape with a jewel-bright Earth hovering in the void. But imagine peering out of such a cupola, as though surveying the ocean from a widow’s walk, for days, weeks, or even years.

What effect would that have on us over time?

Would lunar citizens experience a spiritual or psychological transformation?

If so, Igarashi believes the change would not occur instantly—or even consciously. It would likely take decades of living on the Moon before we would fully appreciate just how different we’ve become.

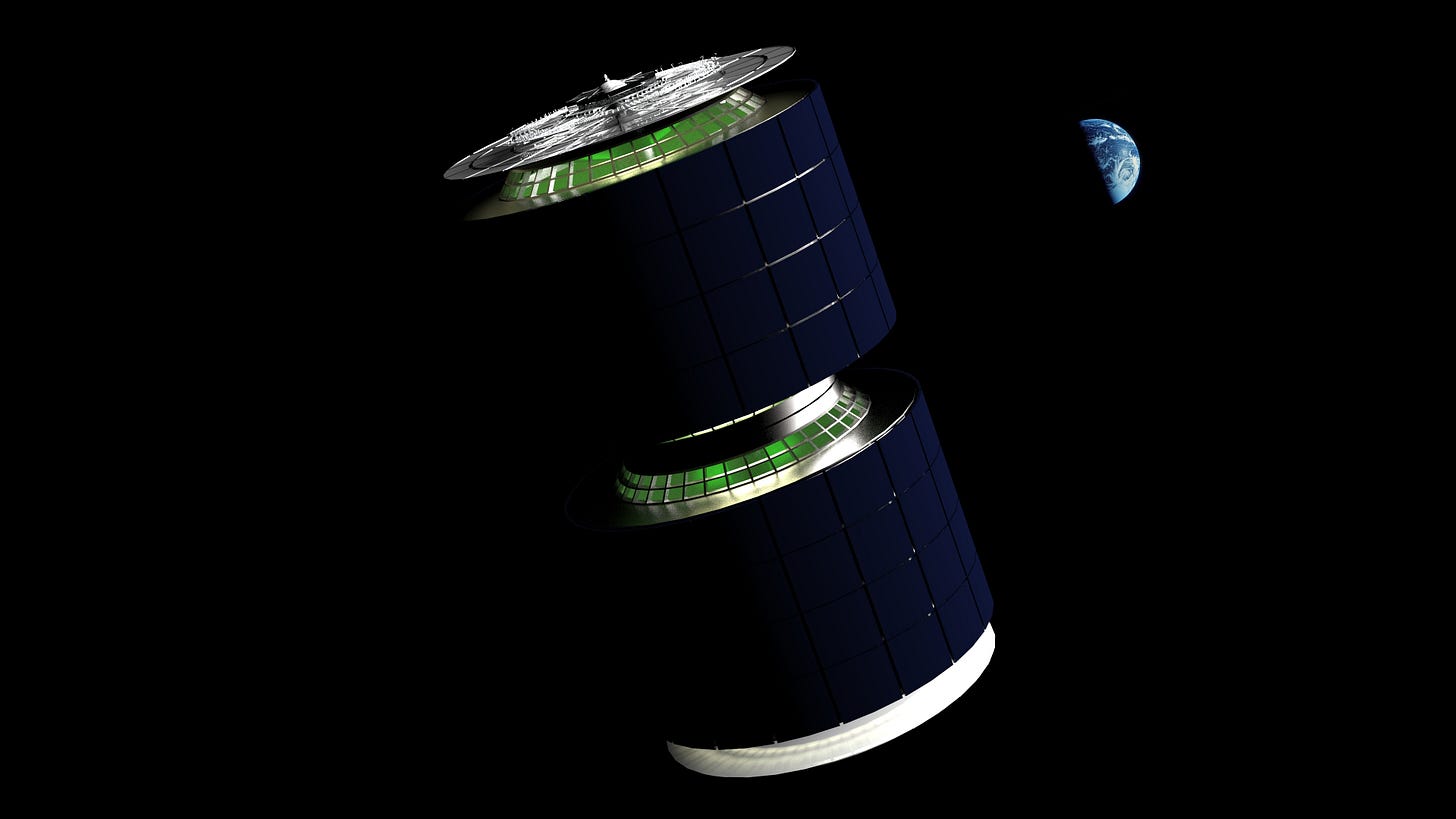

However, Mark Hempsell doubts we’ll ever find out.

“I don’t think people are going to live long-term on the Moon,” he told me with disarming certainty. “They’re going to live in space colonies.”

He then showed me a rendering of a model space colony, and I had the strange feeling that a curtain was parting to give me a glimpse of humanity’s future. The space colonies that Hempsell has designed are massive (four kilometers across) and roughly hourglass-shaped. They would spin in pairs to generate gravity.

According to Hempsell, a fantastic piece of space real estate lies directly above the Moon: “The gravity well in this region is flat, meaning that the energy it would take to travel from one colony to another is less than the energy it takes me to drive to the supermarket and back.”

When I asked how many people could bunk in one of these space colonies, he estimated one to two million—a small nation. And that’s just one colony. Altogether, he calculates the area above the Moon could support a population of 10 billion future humans.

“I think we could live very well there,” he said. “If you’re happy with city living on Earth, you wouldn’t know the difference.”

The only reminder that you’re trapped inside a giant metal ship would come if you happened to look out a window or throw a football. Due to the Coriolis effect, balls would soar in an unexpected trajectory, making golf on the space colony a challenge. Though on the plus side, Hempsell notes, you’ll never again have to worry about the weather.

“If you want a future with material wealth and better living conditions, if you want to enjoy the fruits of our technological civilization, this is the only route you can go down,” he concluded. “Our choice is between a space age or stone age.”

I suspect you would have to use force (and possibly a borrowed ax) to get Thoreau on a gyrating space colony.

It’s hard to imagine the bearded wildman of Walden aboard a gleamingly antiseptic ship, especially one with urban density and lavish amenities.

It’s not that Thoreau fetishized poverty or preferred simplicity for simplicity’s sake. He simply saw material wealth as fool’s gold—“treasures which moth and rust will corrupt and thieves break through and steal”—and thought it wiser to keep his precious metals in the shallows of Walden Pond in the form of gold and silver fishes that would circle his bare ankles like a string of jewels.

Thoreau retreated to the wilderness because the move made him filthy rich: “I have, as it were, my own sun and moon and stars, and a little world all to myself.”

No matter how glossy the sales brochure, Thoreau would recognize the true cost of trading Earth for a luxury space colony—the feel of damp grass underfoot, the smell of burning leaves, the sight of an icebound tree glowing in the winter sun.

It’s a steep price, as anyone who has experienced a lengthy indoor convalescence can attest.

In the future, as we wring our hands over whether it’s more profitable to stay or leave the planet, the invalids will quietly remind us that wherever we hang our space helmets, we will always be one illness away from a private stone age.

And this brings me to the caregivers.

The people who would choose to forgo the opulent solitude of Walden Pond, just as they would choose to watch a majestic ship headed for a sumptuous space colony sail away—all so they can stay behind and nurse a sick friend or family member.

Somehow they survive in the harshest of conditions, unshielded and uncomplaining.

The other day, I grimaced watching my mother hoist my laundry basket into the air.

“Your life would be so much easier if I weren’t in it,” I observed.

After she caught her breath, she replied cheerily, “No, it wouldn’t be easier. It would be hell.”

See you on the Harvest Moon!

—WD

P.S. The Lunar Dispatch is growing by leaps and bounds due entirely to word of mouth. I found a way to thank you properly. By using the “Refer” button below, you’ll receive special messages and escalating (albeit intangible) prizes if you manage to recruit 5, 15, or 30 new Lunatics. Godspeed.🫡

Very skilful writing - I like the way you link all those points together.

Your mother is right...