The Cold Moon 2020

Dear Lunatics,

Get ready to crane your neck because the full moon will be riding high in the sky tonight.

December’s full moon is known as the Cold Moon, a.k.a. Long Night Moon, a.k.a. Drift Clearing Moon, a.k.a. Frost Exploding Trees Moon.

This newsletter, meanwhile, is now known as The Lunar Dispatch.

I’ve retired from the fortune-telling game.

From this point on, I’ll be focused on bringing you the latest Moon-related news.

There’s a lot going on up there.

And down here.

Anyways, here we go…

Last Saturday morning, a silver monolith materialized in the Quincy Quarries—not far from where I live. It arrived with no explanatory label or plaque, only a spiraling crop circle carved in the surrounding snow.

In photos that spread across social media like wildfire, the monolith looked alien, as in profoundly out of place. Its dull metal stood out against the alabaster snow and the heavily graffitied quarry, whose rockface is dappled with messages such as “You are conscious matter” and “Birds aren’t real.”

We are in the midst of a global outbreak of monoliths.

It all began last month when a team of biologists in remote Utah was conducting an aerial count of bighorn sheep and spotted a ten-foot pillar gleaming in a red sandstone canyon.

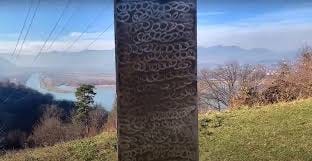

The following week, a similar structure—this one covered with strange looped markings—turned up on a Romanian hillside.

A few days after that, a jogger in California discovered one protruding from a pebbly mountaintop.

As I write this, just five weeks into the craze, fifty-one countries are currently hosting monoliths.

Monoliths have been the calling card of extraterrestrials ever since the premiere of 2001: A Space Odyssey, a film in which mankind’s evolution is guided by mysterious artifacts—eleven-foot black slabs—strewn across our Solar System by some higher intelligence.

Behind the scenes, these props were a nightmare to create. They had to be carefully carved from hardwood then sprayed with countless coats of graphite and matte paint to achieve an otherworldly sheen. Of the fourteen constructed, thirteen were rejected by the director Stanley Kubrick for tiny imperfections. An advanced alien species wouldn’t make mistakes, would it?

During filming, the polished slab was almost impossible to keep free of fingerprints and fake lunar dust, which would cling to its surface. It had to be air-blasted before takes.

If the monolith of 2001 appears slightly less cosmic in 2021, that’s probably because we all carry a miniature version in our pocket. Audiences at the time, however, were bowled over. At one screening, a moviegoer was so mesmerized by the inscrutable totem that he rushed down the aisle and threw himself through the screen, crying out, “It’s God! It’s God!”

According to Joy Cuff, a visual effects artist who worked on 2001, Kubrick would have been thrilled by the sudden profusion of monoliths today. For anyone who follows UFO sightings—and Kubrick followed them closely—it’s indeed Christmastime.

It reminds me of my time at MIT, where life is punctuated by chance encounters with so-called “hacks.”

Hacks are MIT’s version of campus pranks—elaborate installations that materialize overnight. The tradition stretches back to 1928 when the Dorm Goblin, the first documented hacking group on campus, lured a cow onto a dorm roof, an incident that gave rise to the title of Neil Steinberg’s book about college pranks, If at All Possible, Involve a Cow.

In the years since, MIT hackers have transported an entire dorm room to the frozen surface of the Charles River and placed a variety of objects—a police car, a fire engine, an Apollo Lunar Module—atop the Great Dome, which is 150 feet high and accessible only through a 3-by-4-foot hatch.

And yes, they planted a black monolith in Lobby Seven in 2001.

Hacks are generally judged by their delightfulness and degree of technical difficulty. Damaging property is considered gauche, as is using a stolen master key or brute force (“the last resort of the incompetent”).

Hack etiquette is spelled out in the MIT student handbook, and strict adherence to its commandments is the only reason these pranks have been tolerated by the Institution for over a century.

Do not hack under the influence.

Do not steal anything.

Do not hack alone (just like swimming).

Be subtle.

Be safe.

Hackers are urged to carry a flashlight. According to Nightwork: A History of Hacks and Pranks at MIT, “The black canvas of night is the stimulus for invention. And thus most of the work of hacking—the brainstorming, the strategy sessions, the prep, the test runs, the implementation—happens at night.”

Because hackers spelunk into recesses and rafters where no Institute workers venture, they are likely to come across architectural problems before anyone else. They are duty-bound to report these issues to buildings and grounds.

Hackers are also encouraged to think of MIT’s Confined Space Rescue Team, which is tasked with dismantling the installations. It’s classy to leave them detailed removal instructions and edible treats.

Most critically, hackers must not identify themselves. Even if they manage to levitate the campus, they can never take credit.

The monoliths now dotting the globe were not built and erected by hackers. Most of the engineers have already revealed their identities. They’re local artists, brand consultants, struggling Youtubers. A satirical Polish magazine just claimed credit for the Warsaw monolith, which they created as a monument to the year 2020. They say both are gray, gloomy, redundant, too long, and soon to disappear.

By now, most of the monoliths have been removed by authorities or else sold on eBay.

The obelisk on Pine Mountain in California was toppled by three vandals and replaced with a wooden cross. “We don’t want illegal aliens from Mexico or outer space,” one of them told a livestream audience before beginning to rock the 200-pound stainless steel structure. When confronting the unknown, even the tribe of early hominids in 2001’s opening sequence showed more self-restraint.

I never got to touch the monolith in Quincy Quarry. It was stolen within a few hours and no doubt sold for scrap metal.

I’m not too devastated. Aerial photos showed distinctly human footprints in the snow around the edifice—and zero burn marks left by alien craft.

No one seriously considers these monoliths to be extraterrestrial beacons. After all, aliens are far more faithful to the hacker code of ethics. They come at night, they usually involve a cow (see cattle mutilations across the Midwest), and they steadfastly refuse to take credit.

I never executed a single hack while studying at MIT. As a non-engineering student, I was sure I would end up dropping an upright piano on a classmate.

I belonged (or fancied I belonged) to a different breed.

Artists are the opposite of hackers.

We abhor sobriety.

We steal wantonly.

We work alone.

We are rarely subtle.

And we avoid safety.

Most of all, we are desperate for credit. We sign everything. We will rappel down the sheer wall of a quarry just to spray paint our names in giant bubble letters.

Hackers don’t need the acclaim. According to Why We Hack, an anonymously published manifesto, they are perfectly satisfied as long as their work has brightened a stranger’s day.

But for artists, a passing smile is not enough.

We’re not satisfied until people are running down the aisles and diving headfirst through the screen.

Until next month.

—W

I just found this page an hour ago and I haven’t stopped reading. I scrolled down to find less popular works out of curiosity and to learn about “what works and doesn’t.” So far, it all works. I’m loving each ride. I’m always curious what you’re going to reveal, be that new information, a connecting thought, or a turning point in the story.