Dear Lunatics,

First of all, thank you for the many well wishes I received after last month’s dispatch.

I’m happy to report that I am home from the hospital at last, though I seem to have brought some of the hospital home with me. I am tethered to a droning machine that makes each trip to the bathroom as laborious as a spacewalk; I am on a medication regimen that would suggest I am about to venture into the Amazon jungle; and I am forbidden—on doctor’s strict orders—to lift anything over ten pounds.

Given my current state, I thought I would let a group of dead poets do the heavy lifting tonight.

In verse, the Moon has been compared to nearly everything. Ever since that bovine first jumped over the Moon, poets have been straining to come up with fresh similes.

If only poets had a list to consult, they would know which images have already been used.

I decided to compile such a list.

Of course, as soon as I started, I realized it would be easier to catalog the things the Moon has not been likened to.

The Moon has been called:

A knight in armor (Vachel Lindsay)

A white knuckle (Sylvia Plath)

A graveyard for light (Sinan Antoon)

A broken mirror (Adrienne Rich)

White mares (Amy Lowell)

A nocturnal cyclops (Mina Loy)

A child’s balloon, forgotten after play (T. E. Hulme)

Phosphorus on vagrant waters (Pablo Neruda)

The queen of everything (Lucille Clifton)

When it comes to attracting metaphors, the crescent moon has done very well for itself:

A silver scimitar (Sara Teasdale)

A chin of gold (Emily Dickinson)

A rim of plate (James Merrill)

A little fluttering feather (Dante Gabriel Rossetti)

A fingernail held to the candle (Gerard Manley Hopkins)

The smile of a sleeping baby (Rabindranath Tagore)

The poet John Hollander went further than anyone in his attempt to represent the crescent moon on the page:

As I accumulated these lunar comparisons, it became necessary to create a separate, quarantined section for absurdly sexist similes.

For many male poets of the past, the Moon resembled nothing so much as an old crone:

Shakespeare compared the Moon to a stepmother or widow “withering out” a young man’s inheritance.

Sir Philip Sidney thought the way the wan-faced Moon climbed the sky was like an elderly woman trying to manage a flight of steep steps.

To James Merrill, the Moon was a gaunt, half-dead old woman who brought to mind Madame Curie stirring her toxic vats.

According to Oscar Wilde, the Moon wasn’t a woman with one foot in the grave; she was a woman already dead and rising from the tomb.

For other male poets, the Moon wasn’t a decrepit dowager, but an attractive, scantily clad young woman.

“The wind has blown all the cloud-garments / Off the body of the moon / And now she's naked, / Stark naked.” (Langston Hughes)

Unsurprisingly, D. H. Lawrence was the most explicit: “The white moon show like a breast revealed / By the slipping shawl of stars.”

“Loie Fuller in the Moon” Credit: NYPL Archive

Eventually, having exhausted my personal memory of Moon-related poems, I turned to a Large Language Model, which could quickly trawl every word ever written and supply me with other lunar lines.

Or so I thought.

According to ChatGPT, the Moon has been compared to:

A crystal mirror (Augusta Webster)

A pearl in the night’s black hand (James Weldon Johnson)

A lonely hitchhiker (Jack Kerouac)

A drunken dancer spinning across the endless void (Gregory Corso)

A darkened mirror reflecting life’s quiet despair (Gwendolyn Brooks)

The bloom of a white flower (Octavio Paz)

There was only one problem with these additional metaphors.

None of them were real.

The poets are real, but the lines and the poem titles are fictitious.

To the surprise of their creators, these AI generative models “hallucinate.”

They dream.

In my opinion, it’s the most human thing about them.

I, too, once hallucinated a poem by Octavio Paz.

I dreamed I was at a poetry reading by the deceased Mexican poet. “Don’t judge,” he beseeched us with a charming smile. The poem he was about to read was new and yet to be revised.

As soon as I woke up, I wrote the poem down exactly as I heard him speak it in the dream:

You have been living in italics for two years.

Go where the oaks die.

That is what the poet does,

turns the moon into a pen

bleeding through your breast pocket.

I take you to the store.

My horseshoes laugh

on the warm pavement.

I am happy to be alive.

I have died.

No matter how many moon metaphors I amass, it will never be enough.

The Moon is as hard to hold as a globule of mercury.

No simile will ever capture it.

One poet from San Francisco, Jack Spicer, expressed an ambitious yearning:

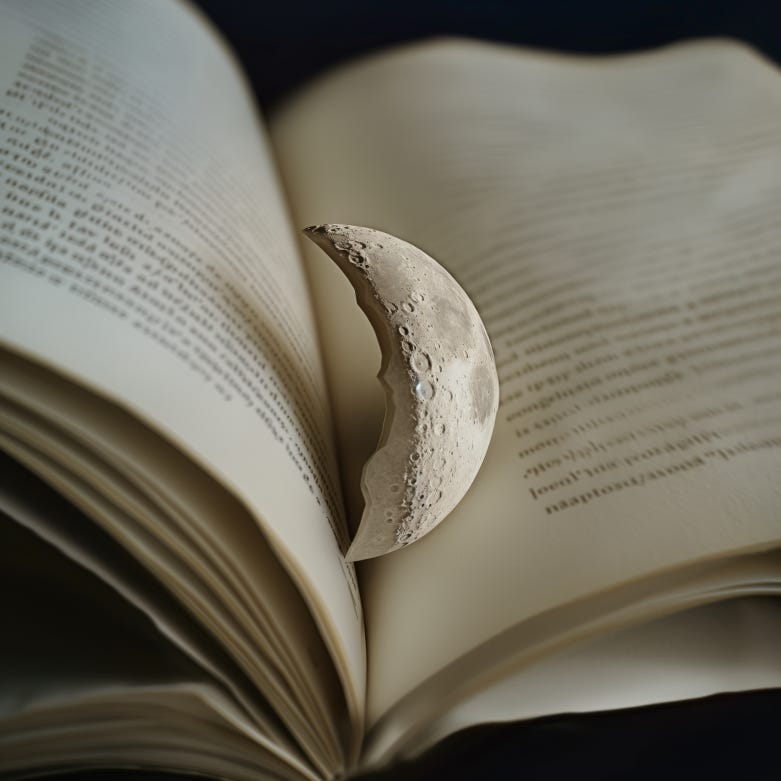

“I would like to make poems out of real objects. The lemon to be a lemon that the reader could cut or squeeze or taste…I would like the moon in my poems to be a real moon, one which could be suddenly covered with a cloud...”

I wonder if the poem Spicer was seeking to write was simply the world around us—and that poem has already been written.

Even if a poet could shrink the Moon and flatten it between the pages of a book like a crushed prom flower, it would no longer be the Moon—it would be a souvenir of itself.

But there’s one more reason why poets will never exhaust the Moon.

Tonight, when the Oak Moon rises in the eastern sky, it will not be just one moon. It will be one of millions.

Think of all the reflected Oak Moons that will shine on tide pools and city fountains, slide over ocean crests and car hoods, swim in puddles and oil slicks.

It’s as if, each month, the full moon and its countless reflections are racked, struck, and scattered across the earth like so many billiard balls.

The full moon is legion.

And any poet who thinks they can confine it in their verse is dreaming.

See you on the Wolf Moon!

—WD

I’ve no idea what Octavio Paz would think but I thought the poem was stunning 💗

You are writing my favorite substack newsletter. Thank you!

In my neck of the woods, I can’t see the moon tonight—it is raining. Earlier today we had snow.

The moon figures prominently in this Lorca poem, going through several transformations as the drama unfolds down below. It is a favorite poem of mine.

https://poets.org/poem/romance-sonambulo