Dear Lunatics,

Tonight, we howl at the Wolf Moon.

But be careful.

In January, moon-watching can cost you a toe, a finger, the tip of your nose.

I really don’t know how Rumi did it.

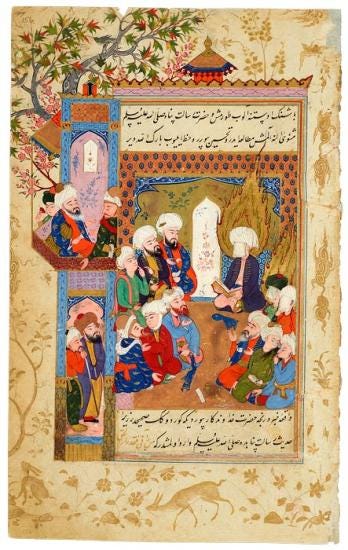

Rumi was a 13th-century Sufi poet who would pray all night on his roof, even in the depths of winter. He also followed a strict regimen of fasting, going so far as to chew on a bitter herb so he would derive no nourishment from his own saliva. Sometimes, when he climbed the roof and looked up at the moon, he was so malnourished that his head would spin, which was precisely the spiritual high he was after.

“I lost my hat while gazing at the moon, and then I lost my mind,” he wrote triumphantly.

I feel especially bad for Rumi’s assistant.

For twelve years, Husām al-Din Chelebi followed Rumi everywhere, scribbling down the lines of poetry that his boss would toss off while washing in the bathhouse or wandering the city streets or dancing late into the night.

This work was especially challenging for Husām, who was so exquisitely sensitive that he would sometimes pass out at the beauty of Rumi’s spontaneous poetry. Rumi would have to revive his scribe before the dictation could continue.

(Poor Husām was sensitive not just to beauty, but also to pain. If he was near a friend in physical suffering, he could feel the agony in his own body.)

With Husām as his amanuensis, Rumi composed the Masnavi-ye Ma'navi, a six-book epic poem comprising 25,000 rhyming couplets and 440 spiritual stories. Rumi joked that the masterpiece was so immense it would need to be carried by forty mules.

Yet in the twelve years they worked together, Rumi never complained about Husām’s frequent fainting. Nor did he complain when his scribe took a year off to mourn the death of his wife.

How many bosses would be so understanding?

There’s a legend in Silicon Valley about Elon Musk’s assistant.

For twelve years, Mary Beth Brown worked as Musk’s faithful personal factotum. The biographer Ashlee Vance described her role:

“If Musk worked a twenty-hour day, so did Brown. Over the years, she brought Musk meals, set up his business appointments, arranged time with his children, picked out his clothes, dealt with press requests, and, when necessary, yanked Musk out of meetings to keep him on schedule.”

Allegedly, in 2014, Mary Beth Brown asked for a raise. Musk said he would consider the proposal and recommended that she take a two-week holiday. When she returned, Musk announced that the past two weeks had proved he could function without her and her position was now obsolete.

I don’t know if this story is true. Musk vehemently disputes it; Ashlee Vance stands by it.

Either way, it demonstrates the kind of human subterfuge that will be impossible if Elon Musk succeeds in building his brave new world.

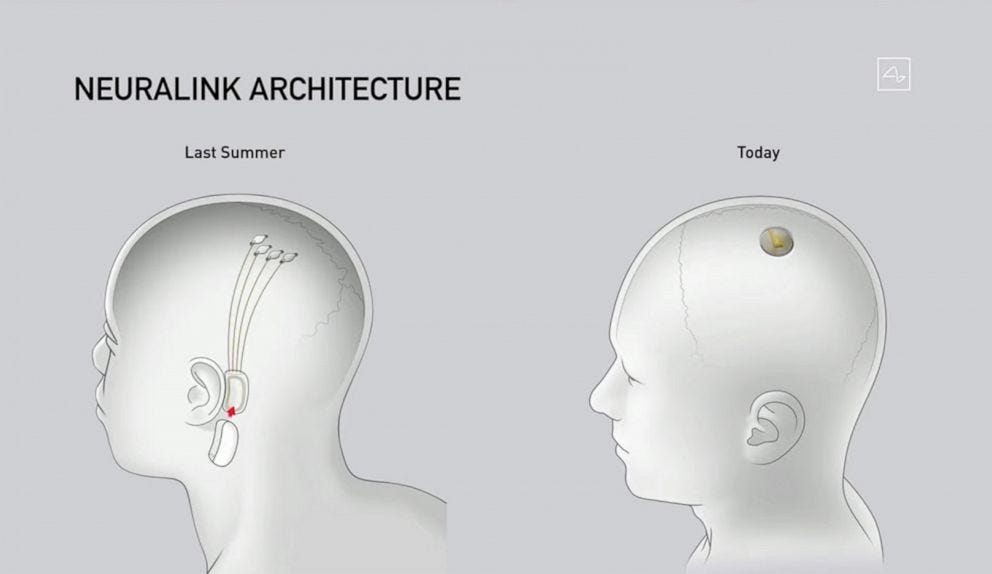

This year, Musk’s company Neuralink will begin implanting microchips into human skulls. These chips will record and stimulate brain activity, making it possible for people to control digital devices with their minds. They will also enable telepathic mind-reading between people, including bosses and their assistants.

I will give Elon Musk this—the man does not think small.

In fact, he is bored by the moon. He shrugs at future moon-landings. "I think we saw that movie in the 1960s…A remake is never as good as the original."

But Musk needs the moon. In his grand vision, it will serve as a stepping stone to his ultimate goal of reaching Mars, where he hopes to die.

Unlike other billionaires bent on staving off death via blood infusions and cryogenic freezing, Musk is not particularly afraid of death. When a bout of malaria nearly killed him in 2001, he says he didn’t even pray.

He feels no need to be remembered. “[M]ost names will be forgotten,” he’s said. “What is the name anyway, it's a name, a name attached to an idea. What does it even mean?"

According to Musk, all that matters is the progress of the human species. And since most people never change their minds, death is necessary to make room for new ideas.

Rumi wasn’t afraid of death either.

In December 1273, as the 66-year-old poet lay dying, the whole city of Konya was in tears. The ground shook with earthquakes. Rumi joked that the earth was hungry and would soon receive a fat morsel.

For Rumi, death would be an eradication of the ego and a blissful marriage with the divine. That’s why he referred to death as his “wedding night.”

But if his death was a wedding, what about Rumi’s best man?

It must have been torture for Husām to sit with Rumi, who was confined to bed and ablaze with fevers during his last days. Torture to mop his master’s brow and hold his wracked body until the end. Torture because Husām would have felt all the pain of his friend’s death with none of the release.

I, for one, will not be lining up to receive Elon Musk’s Neuralink implant.

I can’t imagine my health insurance would cover it, and I’m really not in the mood to shave my head.

But really, I’m not sure any of us could withstand such raw exposure to each other’s pain. To the despair of the sick and the dying. To the sum total of humanity’s loneliness, disatisfaction, and fury.

Simply watching the news leaves me feeling as though I’m huddling on a roof on a cold winter night.

Elon Musk dreams of a future in which our species is networked, merged with technology, and in pursuit of its final destiny among the stars.

But I’m with Rumi, the prolific poet who looked within, the fasting mystic happy to feed the earth.

“There is a moon inside every human being,” Rumi wrote. “Learn to be companions with it.”

—WD

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing (the newsletter is as free as looking at the Moon).

And if you already subscribe, please consider sharing this newsletter with some friends. Thank you! 🚀

If turning skyward to the Wolf Moon helps feed my soul, then reading The Lunar Dispatch is a sustenance of sorts for my heart and mind. Another fine installment, Sir Dowd.

This is stunning. Where'd you learn to write like that?