Dear Lunatics,

Tonight is the Wolf Moon, and I hope you’re howling away.

I’ve been thinking about how wolves hunt in packs and wondering why the Moon should be any different.

According to a recent discovery by astronomers from Northern Ireland, the Moon may have a long-lost twin.

Four billion years ago, a collision may have broken off a large chunk of the Moon, which then soared into Mars’s orbit where it’s been lurking ever since, trapped in the Red Planet’s Trojan clouds.

The astrochemist Dr. Galin Borisov called this newly-spotted asteroid a “dead-ringer” for the Moon.

Twins have been on my mind recently.

Despite having no precedence in their respective families, my cousin and her husband are pregnant with twins. They’re non-identical, though they look indistinguishable on the sonogram: two curved spines, two cauliflower brains, four paddling legs. Their tiny bodies glow like twin moons on the black print.

Science can offer no explanation for the random appearance of non-identical twins. They attribute it all to chance ( about 1 in every 250 pregnancies, roughly). For all they know, the fertility goddess of the Moon is pulling the strings.

Identical twins, on the other hand, are widely believed to be tied to heredity. Human rhymes tend to run in families.

But I think identical twins may be an endangered species.

NASA was able to conduct a remarkable experiment in 2015. Astronaut Scott Kelly was sent to the International Space Station for a year, while the control subject, his identical twin brother Mark Kelly, stayed on Earth.

When Scott returned, the twins were poked and prodded by dozens of researchers intent on determining what effect a spell in space has on the human body.

They discovered that Scott had suffered DNA damage and a shortening of his telomeres, a process usually associated with aging.

"So if 10 years from now, I look like I'm 60 and he looks like he's 80, you'll know what happened," his brother Mark joked.

In the future, as space travel becomes commonplace, so too will the divergence of identical twins. When one twin decides to study abroad in Florence while the other chooses to spend a semester on the Moon, they will forever forfeit their genetic equivalence.

But that’s just the beginning.

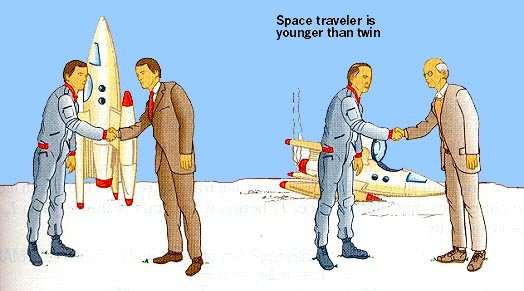

The Twin Paradox is a famous thought experiment in physics and it goes like this:

Twin A climbs into a rocket ship and zips around the galaxy near the speed of light; meanwhile, Twin B stays earthbound.

While Twin A is experiencing his flight as a short jaunt, time on Earth will be passing at an alarming rate.

When Twin A returns home, Twin B will be older than him—perhaps even an old man.

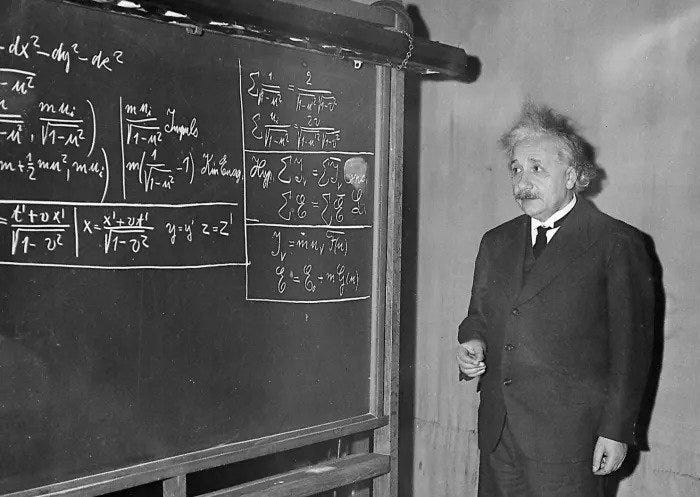

*If you’re wondering how the Twin Paradox works, it has to do with special relativity and gravitational time dilation—but I don’t have the time to explain it here. You’re just going to have to take this guy’s word for it:

I’m mostly interested in the Twin Paradox as a personality test.

There are two types of people in the world: those who would choose to ride on the rocket ship and those who would choose to stay behind.

Which are you?

Personally, I think there’s something courageous yet cold-blooded about hitching the ride.

Just imagine the macabre scene that awaits you when you return.

The awkward embrace with your elderly twin, who offers you a glimpse of your future old and senile self.

And then, over your twin’s shoulder, you see grandchildren lined up. Little strangers with unfamiliar faces. Just pairs of eyes and ears.

You’d be greeted as a returning hero, but would it have been worth it? You would have traded decades with family and friends, all to be the rabbit pulled out of spacetime’s hat.

“There are two kinds of people in the world,” Dear Abby once wrote. “Those who walk into a room and say, ‘There you are’ and those who say ‘Here I am.’”

It’s possible that all of us have twins, either in a parallel universe or somewhere in the far reaches of infinite space, where another Earth and another you are bound to turn up eventually.

For some reason, whenever I imagine my own twin, he’s living a better life than me—a charmed life. He didn’t spend half his childhood huffing on a nebulizer, and he certainly hasn’t spent his thirties weighed down by intractable health problems.

I know it’s wrong to begrudge someone else their good fortune, much less a sibling, but I find it hard not to be jealous of my healthy twin.

They say there are two wolves inside of us, a good wolf and an evil wolf, and the one that wins is the one we feed. But I just can’t stop throwing red meat to my evil wolf.

My twin has got everything, I think bitterly, and all I’ve got is writing.

Of course, writing is not nothing.

“Writing is a way to have a life,” the English novelist Hilary Mantel said, “even if it has got to be second-hand."

Mantel is best known as the author of Wolf Hall, a work of historical fiction so uncannily realistic that critics were left wondering if the author had time traveled into the past to take notes.

Mantel’s second-hand life was the result of her long battle with endometriosis, which left her plagued by chronic pain and frequent illness.

"If I hadn't had to battle so long and hard for a diagnosis, if they had caught it five years earlier, my life would have been completely different," she wrote.

Some people have said, glibly, that her loss was literature’s gain.

But what claim do we have on an artist’s life or happiness?

And what about the unwritten books she took with her when she passed away in September? Should we mourn those more than we mourn her?

She was only 70 years old.

Hilary Mantel was my favorite living writer (now just my favorite writer, without adjectives) because she always told the truth, especially in fiction.

If she had been asked point-blank in an interview, “Art or life?”, I have no doubt she would have given the honest answer:

Art, but I wish it were life.

If I had a twin, identical to me in every way, and one of us was offered a seat on a time-jumping rocket ship, I would fight for it. Because surely, in a technologically-advanced future, I’d stand a much better chance of being healed.

Think of the robot doctors who make instant, infallible diagnoses…

Of the finger pricks that warn which medications will give you side effects…

Of the swift cheek swabs that can grow new organs…

Hell, I’d probably slug my brother in the stomach, hop aboard the rocket ship, and close the air-locked hatch behind me without a second glance.

Of course, I wouldn’t forget about my twin, the one I left doubled over on the tarmac, gasping in a cloud of white rocket steam.

He’d haunt me.

Whenever I closed my eyes and thought of him, I would see him clearly—as twins can sometimes do.

I can see him right now, actually.

It’s the year 2069.

He’s creaking out of bed at 3 am. Age has only exacerbated his insomnia.

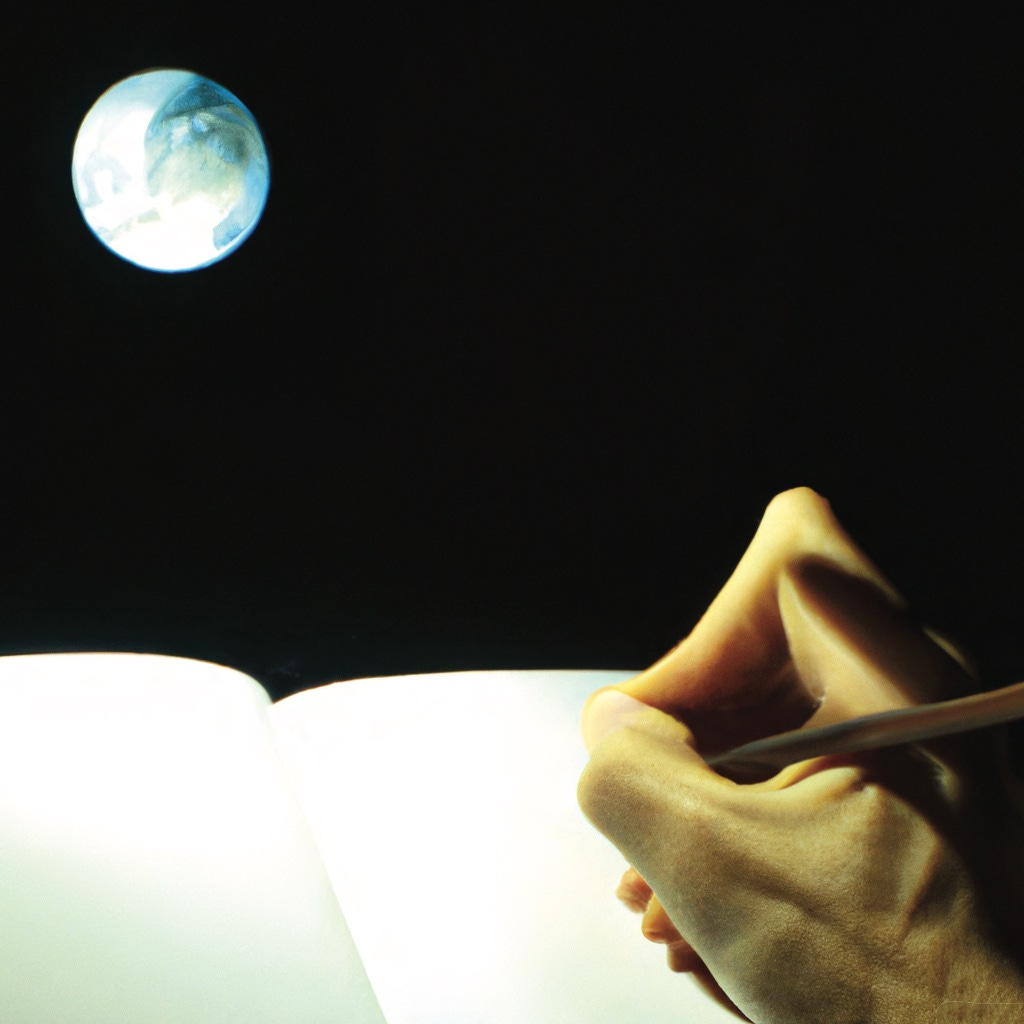

He makes a pot of coffee, or, rather, orders a pot of coffee to make itself. Then he sits at his kitchen table and begins to write a letter the old-fashioned way.

It’s a farewell letter of sorts. An explanation to his brother why he couldn’t wait for his return any longer. Truth be told, he’s amazed he’s made it this long. As his favorite novelist once wrote, “There are people who find life hard and those who find it easy.” He finds life hard—and after 85 long years, he’s done with hard.

He writes and writes. He pats dry a coffee spill. He searches for the right words. Before he knows it, he’s cheering up. He’s always loved the simple pleasure of scrawling letters across a blank page, like tracking footprints on bright lunar soil.

It’s a paradox—to find so much joy in penning your own suicide note that you change your mind about the whole thing—but it’s seen him through many dark nights, and you can survive for a long time on a paradox.

He tears up his finished letter, walks outside, and releases the scraps of paper into the air. January nights are still cold and windy in the future. He shivers and looks up at the black sky. His brother is up there somewhere. He hears wolves howl in the distance. A flock of geese passes overhead. A flying car crosses the moon.

—WD

PS. For more on the Twin Paradox, check out TED Ed’s explainer:

Thank you for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to this newsletter, which is as free as looking at the Moon.

If you’ve already subscribed, please consider sharing this post with some of your fellow Earthlings 🚀.

Interesting. Emotional. Futuristic.

Always love the way you interweave topics.

“It’s a paradox—to find so much joy in penning your own suicide note that you change your mind about the whole thing”

This line hit a totally different chord. 🔥

Happy New Year WD!!

This felt like a synchronous read having just watched The Double Life of Veronique. Beautiful film — and beautiful writing here.