Dear Lunatics,

One day last summer, I sat my parents down to have the talk.

“Look, when the time comes, and hopefully that time will be many moons from now,” I began awkwardly, “how would you two prefer…to be buried?”

“Do we really have to discuss this?” my mother said wearily.

“Yes,” I insisted. “It’s important,”

My father yawned. “Just bury me in the backyard.”

“Ok,” I said, “But I’m pretty sure that’s illegal, not to mention the negative impact it would have on the resale value of the house.”

“I don’t like the idea of being put under the ground,” my mother said, shuddering. “It gives me the creeps.”

I imagined an extravagant mausoleum. There goes my inheritance, I thought.

“How about one of those shelving units?” she suggested.

“A wall crypt?” I said.

“Yeah, that’s it.”

“OK,” I said, turning to my father. “And how would you feel about that?”

“Whatever your mother wants,” he said, dropping his voice to add, “just like in life.”

My parents did not inquire about my burial preferences.

When I was growing up, I harbored a romantic idea that my remains would be detonated in a fireworks display.

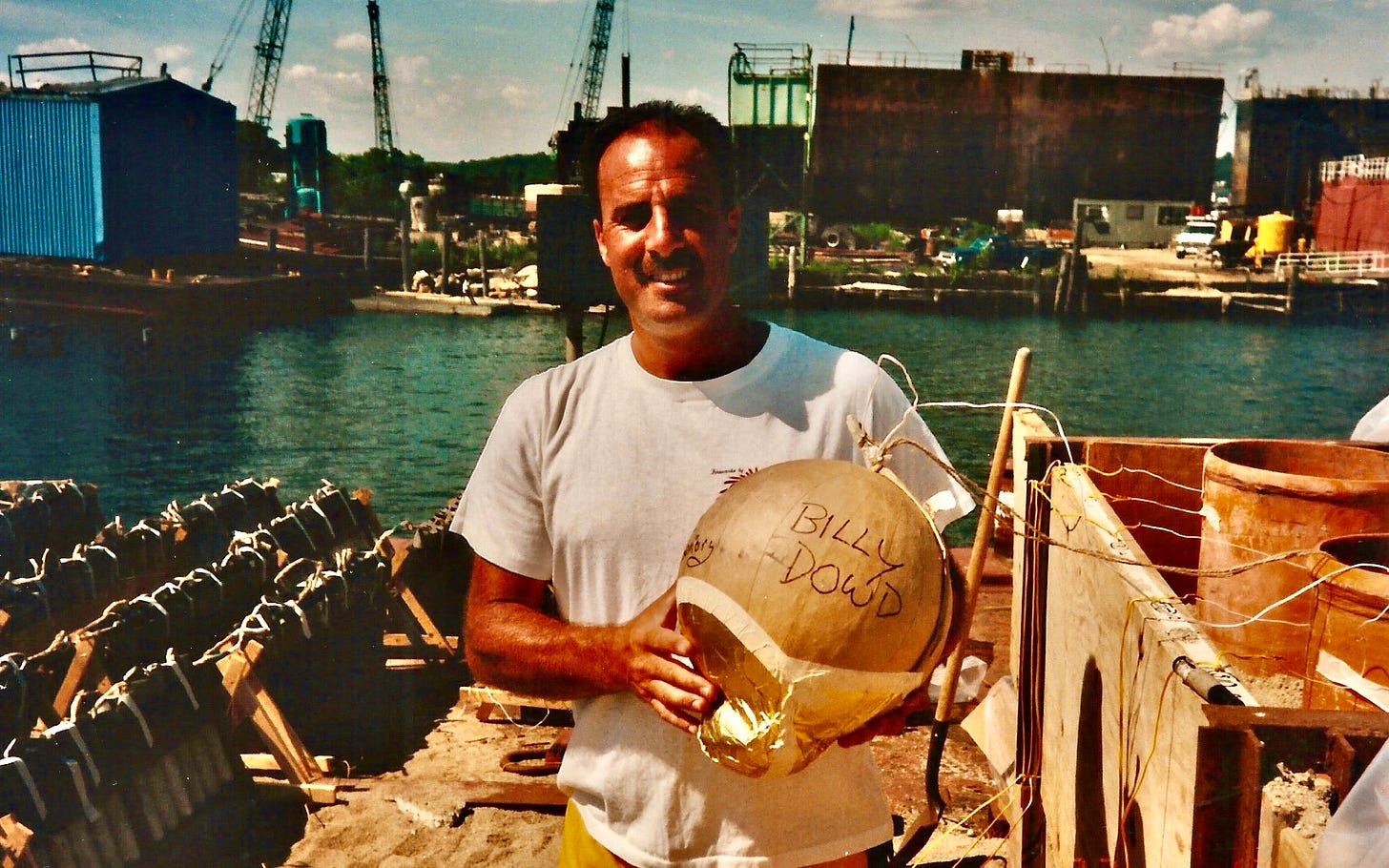

It didn’t seem that far-fetched. My Dad’s coworker, Pat Bosco, who was like an honorary uncle to me, moonlighted as a pyrotechnician and used to scrawl my name on the shell of Fourth of July fireworks.

But one Independence Day, that idea went out the window.

I was attending my town’s annual fireworks display when the winds shifted and hot ash rained down on a screaming crowd. We all fled in terror, leaving behind our singed folding chairs and soot-covered picnic blankets.

If people cry at my funeral, I don’t want it to be because flaming remnants of my body have landed in their eyes.

After that debacle, I decided I should just be buried at the town cemetery, where one of my best friends worked. Sometimes, on stormy nights, I would meet him for a beer. He would stumble into the bar, bedraggled, his pants covered in muck, and tell me how he’d just spent the last several hours shoveling mud from a rain-soaked grave the way you would bail out a sinking boat, all while a grieving family stood over him, sobbing under their black umbrellas.

My friend died a year ago this month.

The whole cemetery, which he cared for with stoic pride, feels like a monument to him now. He’s not buried there—as someone close to him told me, who wants to be buried at their workplace?

It’s a good point.

But maybe I do.

Celestis Memorial Spaceflights has been sending human cremains into space since the 1990s. They offer space burials in several packages: some rockets orbit the Earth, others are blasted into deep space on a “permanent celestial journey,” while some—and these are the ones that interest me—are sent to the Moon.

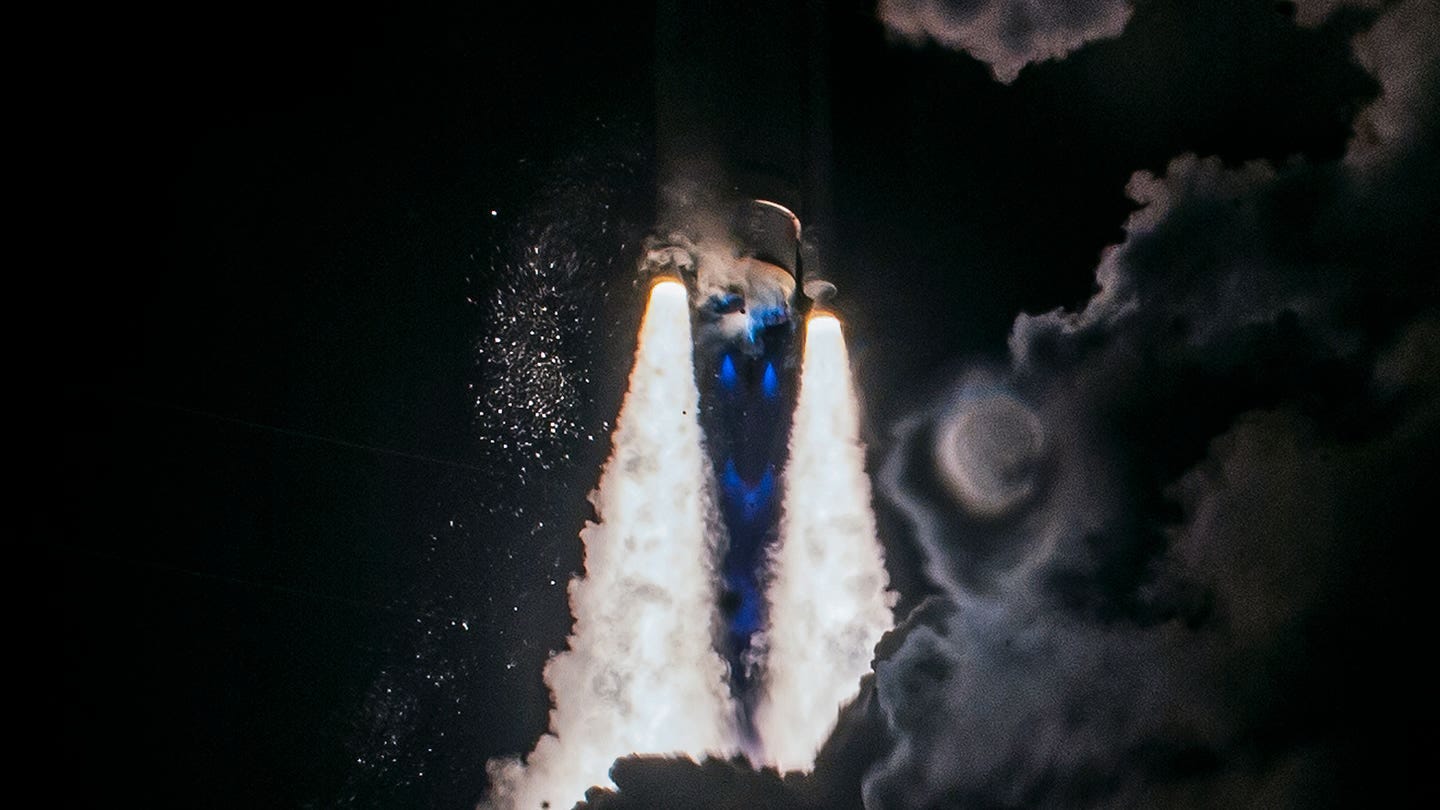

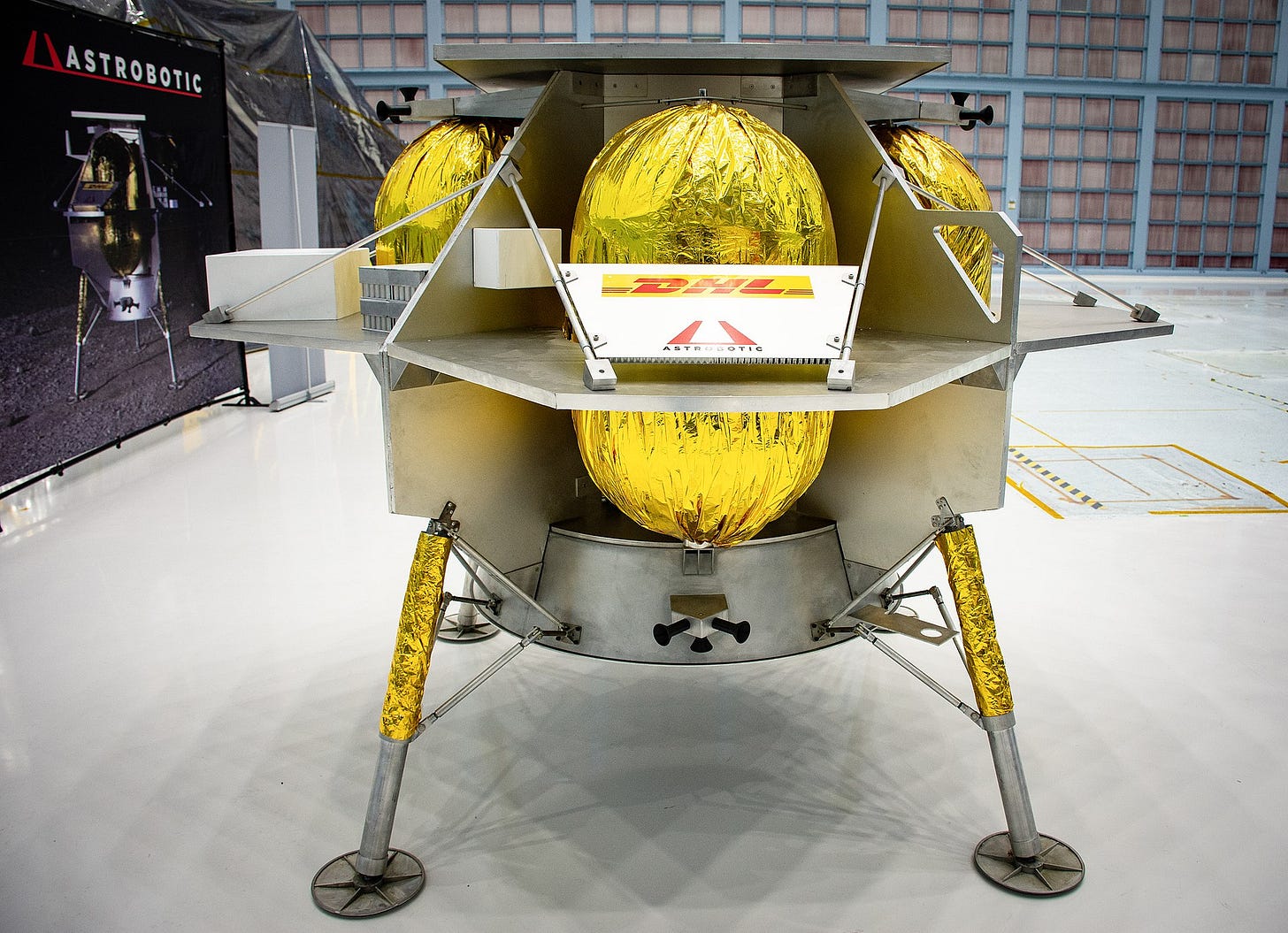

When I began looking into Celestis, I learned that their next payload was ready to board a golf cart-sized lunar lander soon to be propelled by a Vulcan Rocket from Cape Canaveral to a volcanic plain known as Oceanus Procellarum—aka the “Ocean of Storms”—on the surface of the Moon. On board would be dozens of cremains, many of them, according to brief biographical descriptions on the website, inveterate Star Trek fans.

Say what you will about these uber-fans, but life on Earth is looking more and more like an episode of Star Trek. Just within the past week, William Shatner himself was tweeting about ten-foot aliens supposedly spotted in the center of Miami, while footage of jellyfish-shaped UFOs drifting over Iraq has sent the internet into a furor.

I admit I was initially cynical about the Celestis Space Memorials. The price tag for a lunar burial—$12,995—seemed excessive, though the cost of sending a beloved pet’s remains was slightly less, ringing in at $12,500. (As the website boasts, “It’s one giant leap for petkind!”)

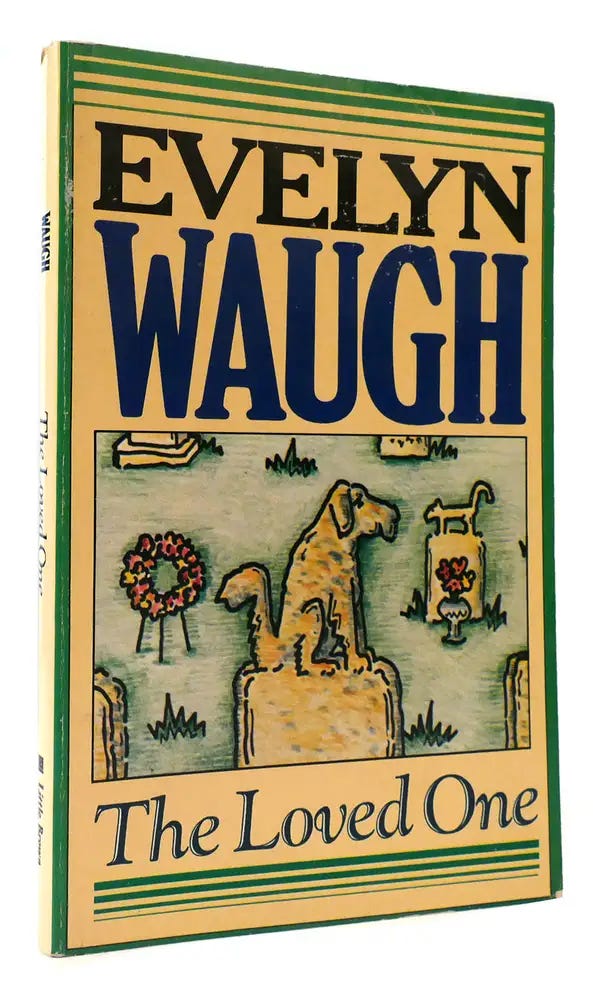

I was reminded of the novelist Evelyn Waugh’s satire about the American funeral business.

In The Loved One, the main character Dennis Barlow lands a job at a Los Angeles pet cemetery called Happier Hunting Grounds, the type of cemetery where a rich owner’s canary is laid to rest in a tiny grave with “a squad of Marine buglers…sound[ing] Taps.”

At one point, it falls to Dennis to scatter the remains of a tabby-cat from an airplane into “the slip-stream over Sunset Boulevard.”

Yet my cynicism was put to rest after two long conversations I had last fall with a Celestis representative.

First of all, she reminded me that the average funeral costs $11,000, so Celestis is not price-gouging the grieving.

She also told me about the celebratory nature of the launches, which families are invited to attend in person. Rather than stare down into a muddy hole, they turn their brightly lit faces upward as their loved ones ascend into the heavens.

Apparently, there are cheers, hugs, and tears of joy.

You may wonder why I found my funeral arrangements so pressing. Even when we’re healthy, we all know that Death is riding his pale horse over wet sand day and night, coming for us. But when you’re sick, it feels as though Death is riding a Vulcan rocket, and sometimes, at your weariest, you wish it would just hit its mark already.

Evelyn Waugh certainly felt this way in his early adulthood. He was depressed by his floundering career and the implosion of his marriage to Evelyn Gardner, though personally, I think their divorce averted what would have been the world’s most confusing headstone.

One night, his thoughts “full of death,” Waugh walked down to the beach, took off his clothes, wrote out a note, and swam out to sea. “It was a beautiful night of a gibbous moon,” he remembered years later. But before he could reach the point of no return, he was stung by jellyfish. Then by another jellyfish. They were everywhere. He swam back along the “track of the moon” to the beach, where he re-dressed, tore up his note, and “climbed the sharp hill that led to all the years ahead.”

Obviously, when the Celestis payload launched on January 8th, 2024, my handful of dust wasn’t on it. No jellyfish stung me—I just felt the tentacles of friends and family wrap around me and keep me tethered to this Earth.

What did make it aboard the Vulcan Rocket were my words. The Arch Mission Foundation took roughly 60 million pages of pictures and text, etched them into a DVD-sized disk of nickel, and tucked this “Billion Year Archive” into what I like to imagine was the glove compartment of the lunar lander.

On the Arch Mission Foundation website, anyone could reply to the following queries and have their answers sent to the Moon:

What do you wish to say to the future?

What would you like the future to know about you?

What would you like the future to know about us, humanity and our time on earth?

I weighed my words carefully, reasoning that they would undoubtedly be the longest-lived words I would ever write.

Not long after the lunar lander launched on January 8th, the spacecraft began bleeding fuel. With its onboard propulsion systems leaking, the lander didn’t have enough gas to reach the Moon. Ten days later, it fell back to Earth, burning up in the atmosphere over the Pacific Ocean.

Had my ashes been aboard, I would’ve had the fireworks funeral I’d always dreamed of.

But my words were gone.

To commiserate, I reached out to the Pittsburg poet Jim Daniels, who was the official Moon Poetry Consultant for the MoonArk, another project that hitched a ride aboard the doomed lunar lander.

Daniels’s job was to compile poems about the Moon. (Yes, he included a poem of his own—“how could I resist?” he wrote to me.)

I asked Daniels if he considered the project a moonshot to achieve poetic immortality, to ensure the survival of his writing into the far distant future.

He responded that while he was disappointed for who those had invested years of their life into the project, he wasn’t crushed: “I always saw the project as conceptual, so to be honest never really thought about the survival of the poems in the future.”

He was also realistic about MoonArk’s long-term viability. He wrote: “During one of the many meetings of all these incredibly smart, creative people on the team, somebody said that by the time the MoonArk landed on the moon it'd be the technological equivalent of an eight-track player at best.”

These days, my body feels like an eight-track player. Maybe that’s why I was so dispirited by the lunar lander’s Icarian fate.

It doesn’t matter what posthumous plans you make.

It doesn’t matter whether you send your words or body up or down.

The future is coming.

On horseback or rocket boosters, the future is coming, and it doesn’t care who you are or what you have to say.

The future is coming.

So don’t wait until you’re a pile of ash.

Don’t wait to be loaded into a firework and shot into the sky.

You are the firework.

Go off now.

Go off tonight.

…

See you on the Snow Moon!

—WD

All things considered, this is a very good line: “If people cry at my funeral, I don’t want it to be because flaming remnants of my body have landed in their eyes.”

Lots to think about here; thank you. Challenging to wake and engage with each new day as if it was July 4th when so many of them feel like July 5th. Still, though, the possibility offers hope.

This all means you need to hang around long enough for the technology to improve, and maybe the price to come down. Please.