Full Snow Moon 2026

Paint me a picture

Dear Lunatics,

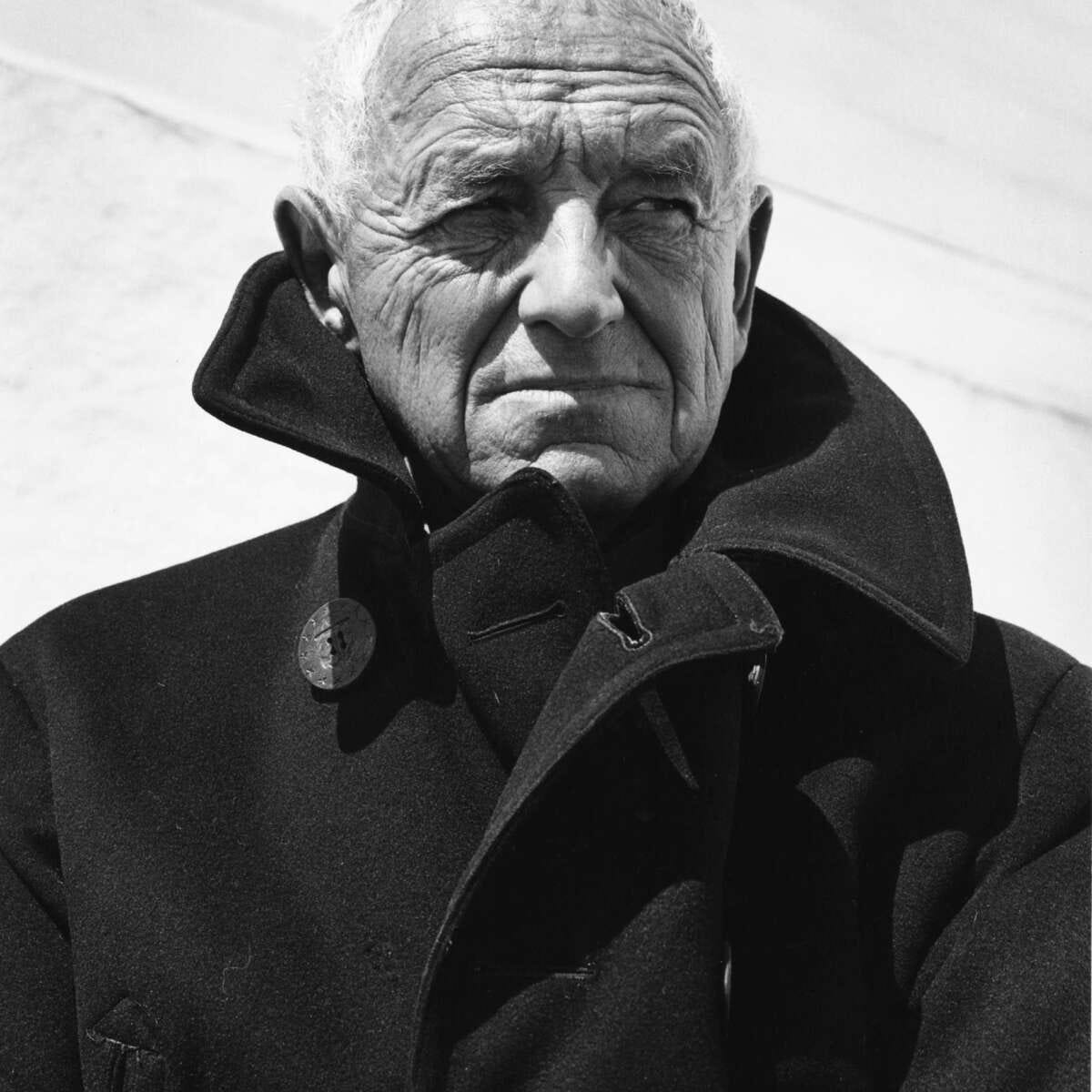

It’s already dark on the night of the Snow Moon, and I have nothing written. Not one fleck of paint on the blank canvas of this newsletter. Maybe I should take inspiration from Andrew Wyeth, who, whenever he was stuck on a painting, would wait until dark, prop his half-finished work against his barn, and stare at it in the moonlight.

Unfortunately, it’s 7 degrees outside in New England, and I don’t own a winter coat half as formidable as Wyeth’s.

For painters, the moonlit night is the nightmare subject. When you can’t even make out the colors on your palette, what hope is there for the canvas itself?

Of course, that hasn’t stopped a few brave artists from taking a blind stab with their brushes. So, that’s what we’ll do tonight: hang some paintings on the wall of this newsletter and have a moonlit exhibit.

Arkhip Kuindzhi’s Moonlit Night on the Dnieper, 1880

A fashionable crowd gathers in St. Petersburg, clutching tickets to the most unlikely blockbuster in Russian art history: a one-painting exhibition. Inside, where the gas lamps have been dimmed and the gallery walls draped in black, hangs a single canvas. As visitors’ eyes adjust, an astonishing illusion takes hold: a smoldering full moon appears genuinely to glow on the surface of the painting. A woman gasps, convinced a lamp must be hidden behind the frame; several gentlemen crane their necks to peer behind the canvas for a bulb or trick mirror. They find nothing but stretcher bars and dust. The artist’s secret is not trickery but chemistry: he has studied the work of Dmitri Mendeleev, the father of the periodic table, to find pigment compounds capable of maximizing luminous contrast, allowing him to paint the full moon with a ferocious brightness no one has ever seen before.

James McNeill Whistler’s Nocturne in Black and Gold – The Falling Rocket, c. 1875

The High Court of Justice at Westminster is packed—not with the usual criminals but with the luminaries of the London art world, gathered for a trial that will pit a painter against a critic. The painter, a dapper American famous for his dreamily abstract nightscapes, which he calls “Nocturnes,” has sued John Ruskin, the most esteemed art critic in England, for libel. Ruskin’s offense: he panned Nocturne in Black and Gold – The Falling Rocket, a depiction of fireworks over the Thames via splattered gold flecks on a near-black background, and he accused the painter of “flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face.” In the witness box, the painter is asked how long the piece took. “About two days,” he admits. When the attorney asks how he could charge 200 guineas for only two days’ work, the painter responds dryly that he asks that price “for the knowledge of a lifetime.” Will the jury see what Ruskin couldn’t? Will they see the painter’s radical technique, layering veils of thinned oils to mimic the soft, hazy blur of human vision in darkness? In the end, the painter wins the case but is only awarded a single farthing in damages—a verdict that, when combined with legal costs, plunges him into ruinous bankruptcy.

Vincent Van Gogh’s Starry Night Over the Rhône, September 1888.

It’s past midnight in Arles, and a painter is working by the river, his straw hat ringed with candles. The tiny flames dance like a bizarre halo, giving off just enough light to show where his canvas ends and the night begins. A couple of locals linger nearby, half-amused, half-concerned, watching this stubborn Dutchman trying to wrestle colors from the darkness. The painter knows the risk he is taking. “In the dark I may mistake a blue for a green,” he confesses in a letter. But he paints anyway, refusing to retreat to the studio, where his nightscapes tend to come out sallow and lifeless, drained of the electricity he senses in the night air. He paints the Big Dipper wheeling overhead. He paints the town’s amber lights skimming across the surface of the cobalt water. “It does me good to do what’s difficult,” he writes afterward.

René Magritte’s The Empire of Light, c. 1939 – 1967

Imagine walking at midnight along a silent suburban lane. The street is dark. A lamp casts a sad puddle of light onto the pavement, and the upper windows of a house softly glow. Yet looking further up, you see a powder-blue sky and sunlit clouds. You are inside the painting of a Belgian surrealist. In his studio, he has obsessively painted a series of these impossible day-night fusions—twenty-seven variations in as many years. For him, the problem of painting at night has been solved. In fact, it was never a problem at all. Just ignore the rules of nature and create your own reality.

Ma Yuan’s Drinking in the Moonlight, c. 1200

In the imperial painting academy of the Southern Song court, a master painter unrolls a length of silk and prepares his ink. He is composing the scene of a scholar drinking alone beneath a spring moon. In swift strokes, he renders a gnarled pine tree, a seated figure with a wine cup, a few rocks, and a sprinkling of plum blossoms—all huddled in the corners of the composition. The rest of the silk is left untouched. This vast blankness isn’t empty: it is the sky illuminated by the full moon. Perhaps this painter is right. Perhaps blank space makes the most convincing moonlight.

Georgia O’Keeffe’s City Night, 1926

The painter steps out of the Shelton Hotel—the tallest residential skyscraper in the city, where she lives on the twenty-eighth floor. She tilts her head back. The buildings loom over her like black monoliths. The distant moon, a pale oval wedged between these stark walls, is almost incidental—a mere bobble next to the vertical swagger of steel. She takes in this vertiginous street-level scene. She knows, instinctually, that it will become her next painting—a painting that will announce that Nature has been dethroned by the modern metropolis. For her and for her fellow urban painters, the problem of painting the night has been abolished. In the city that never sleeps, the night never truly comes. She won’t stay here forever—the desert beckons—but she will leave behind a record of New York City at night. Not how it looked, exactly. As she will later reflect: “One can’t paint New York as it is, but rather as it is felt.”

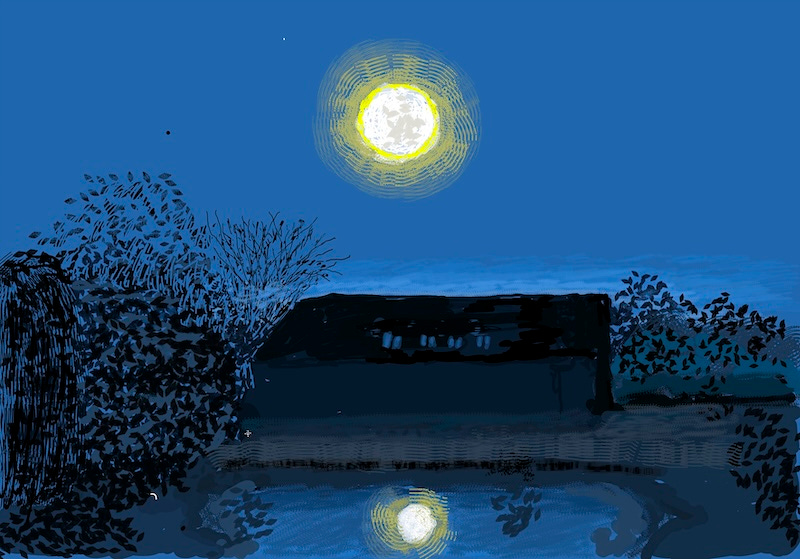

David Hockney’s 26th November 2020, No. 2, 2020

It’s 4 A.M. in Normandy, and an eighty-three-year-old painter is sitting in his garden under a radiant full moon. In one hand, he cradles an iPad, its screen illuminating his face in a bluish glow. With the other hand, he is swiping and tapping, rendering pure blacks and gentle blues on his digital canvas. He zooms in to dash yellow pixels where the moon’s reflection trembles in a pond, then zooms out to judge the whole composition. The tablet is both his medium and his lamp, its light directed away from—and therefore not contaminating—the night scene he is trying to capture. At dawn, he will email the finished painting to friends around the world with a single click. He will later say, “Artists can’t work office hours.”

And neither can lunatics, apparently. I hope you enjoyed this late-night dispatch and that you will now go look at the full moon, already framed by your window and conveniently hung, waiting for you to paint it with your attention.

See you next month on the total lunar eclipse!

—WD

You always manage to come up with something beautiful Will. Thank you for this. And I hope that you are doing well. Sending you health and well being wishes.

I loved this post. Thank you, Will.