Dear Lunatics:

For those of us in the United States, tonight’s harvest moon is just another full moon.

But in Asia, the harvest moon coincides with the Mid-Autumn Festival, a holiday that dates back to the Shang dynasty, when the Emperor of China would pray to the moon for plentiful harvests. Today, people in China still gather with family on the night of the harvest moon to release sky lanterns and gorge on mooncakes.

In Japan, the harvest moon has its own tradition: moon-viewing parties. Some courtiers would picnic under the full moon and recite poetry while downing bottles of sake, while others would paddle out on boats in order to get a closer look at the moon’s reflection.

This custom reminds me of my favorite haiku by Issa:

“Give it to me!”

the child cries

reaching for the harvest moon

Some of us never outgrow this keenly felt need to grasp the moon.

But at some point, we stop crying about it.

Lately, I’ve been wondering about the Artemis Team—the 18 astronauts on standby for the next moon mission—and how they have been handling their mission’s uncertain timetable.

Due to a series of technical, financial, and legal setbacks, it appears increasingly unlikely that the moon landing will take place in 2024 as scheduled.

For someone who may soon walk across its dusty surface, how tantalizingly close does the harvest moon look?

And how maddening is it when that same moon keeps slipping further from your grasp?

I wouldn’t blame the astronauts if they were throwing tantrums at this point.

But do astronauts throw tantrums?

I decided to ask one.

Last week, I reached out to Captain Scott Tingle, who grew up only a few miles away from me in Randolph, Massachusetts.

Tingle recalls drawing laughter from his junior high classmates when he announced his intention to become an astronaut. Today he’s a NASA Flight Engineer who recently spent 168 days at the International Space Station.

In an online message, I asked whether this period of waiting and uncertainty feels interminable.

He responded:

It isn't about me. It's about the country, and humanity. It's about how humans will learn to live away from Earth as we explore space deeper and farther than ever before. I don't feel as if I am waiting for anything, and it is truly an honor to be part of something much greater than myself. Success will be measured as humans return to the moon, and I am excited to participate at any level.

I was moved by Tingle’s response, which conveys exactly the egoless attitude we hope for in our ambassadors to new worlds.

But perhaps this level of selflessness is not surprising in someone who, I imagine, passed a battery of psychological tests before being entrusted to steer a multi-billion dollar spacecraft.

Surely, over the decades, NASA has perfected its selection process, since it consistently produces astronauts who combine ambition and magnanimity in equal measure.

They’re essentially Zen monks with engineering degrees.

Which is necessary, because it requires a certain detachment from earthly trappings to travel into space.

And not just because the black abyss stares back at you.

There’s also the radiation exposure.

Particles riding on solar winds, protons seething in the van Allen belt, ionic shrapnel of supernovas—all penetrate the shields of our spacecraft and eat away at human DNA.

Every astronaut will return to earth carrying invisible damage deep in their cells.

And they know it.

This space radiation reminds me of one Zen master’s description of Enlightenment: it hits you like a “jet black iron ball speeding through the dark night.”1

I’ve been carrying crumpled-up Zen poems in my pockets all pandemic, fishing them out whenever the panic starts to rise.

My favorite is a poem about the nature of existence, which the 13th-century Zen master Dōgen2 composed just before his death:

Being-in-the-world:

To what might it be compared?

Dwelling in a dewdrop

Fallen from a waterfowl’s beak,

The image of the moon.

I’m no monk, but the poem’s lesson seems as clear as water.

We may not be able to hold the moon, but we can behold it—and in that act of perception, the 240,000-mile gulf between us and the moon melts away, along with our delusion that the self and the moon are even separate at all, when really everything is contained within everything else, reflected and impermanent.

Whenever I read it, Dōgen’s poem never fails to light a candle flame in my mind and make my head float away like a sky lantern.

The feeling doesn’t last, of course. Soon, the rice paper catches fire and the bamboo frame falls to earth.

But I never stop thinking of Issa’s sobbing child.

The one who reached for the harvest moon as if it were a golden pear dangling from a low branch.

If a child born today really wants to grasp the moon, they have two choices:

Either they can grow up to become an astronaut, which requires advanced degrees, peak physical fitness, extraordinary psychological balance, and the luck of a lightning-struck lottery winner.

Or they can grow up to become a poet, which requires no formal training, precarious physical health, the temperament of a toddler, and enough misfortune to make the mere sight of the moon in the sky a gift so precious they feel compelled to write about it.

To hold it in a poem.

To suspend it in a drop of ink.

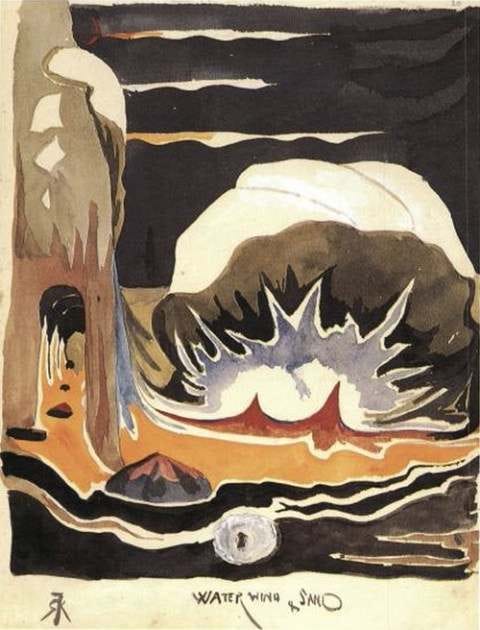

MOON ART

This month’s lunar artwork comes courtesy of Aryan Pathak, the owner of Spin Productions and writer of a newsletter about all things animation.

An animator himself, Aryan used the Tayasui Sketches app to create this digital painting of the Moon looming behind a mountain range:

Aryan’s image reminded me of J. R. R. Tolkien’s Book of Ishness—a sketchbook the author used as an Oxford undergraduate to document the fantastical landscapes haunting his imagination.

At the risk of awaking the sleeping dragon of the Tolkien Estate, which holds the copyright to these visionary illustrations, I’ll include a few examples here:

A decade after he put the Book of Ishness aside, Tolkien took his young family to what he called "a very nasty little suburban seaside resort" in Yorkshire.

During this holiday, his four-year-old son Michael lost his black-and-white toy dog on the beach.

To console Michael, Tolkien wrote an adventure story about a dog named Rover who travels to the Moon where he confronts a wizard and some giant spiders.

Tolkien sent this children’s tale to his publishers but they weren’t interested. They demanded a sequel to The Hobbit.

Tolkien is famous for infusing his legendarium with names derived from a variety of languages, both living and dead. But in this case, I wonder if Tolkien —with his story of a Rover roaming the Moon—inspired the name “moon rover” to refer to the unmanned and remote-controlled space vehicles that motor across the lunar surface.

This seems impossible.

The term “moon rover” started to be used in aerospace circles in the 1960s, while Tolkien’s rejected story was sitting in a drawer in Oxford. (It didn’t see print until 1998.)

Yet Tolkien himself, as evidenced by the Book of Ishness, believed he was drawing from a deep well in the imagination, accessible to anyone with the necessary visionary disposition.

So, who knows?

Stranger things have happened…

If you have any moon-related art you’d like to share, please send it to willdowdwriter@gmail.com, along with your name (and any relevant links) for credit.

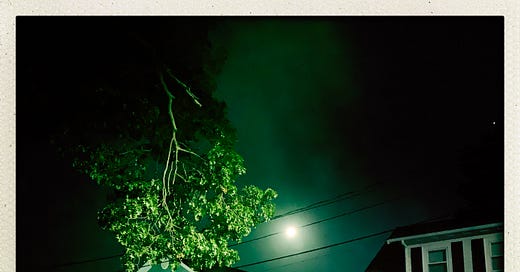

And for you photographers out there:

See you all on the Hunter’s Moon!

—WD

A Zen Wave by Robert Aitken, forward by W.S. Merwin, p. 19.

Zen Action Zen Person, translated by Thomas P. Kasulis, p. 103.

Your newsletter is a unique blend of philosophy, poetry and knowledge.

Just wanted to share this.

In the Indian Lunar based calendar, each month is divided into two parts. The Shukla Paksha (The White Section) and Krishna Paksha ( The Black Section). Shukla Paksha is the 15 day period from New moon to Full moon. The 15th day is called Poornima (usually considered Auspicious).The Krishna Paksha starts from the Full moon day to the New Moon day ending on Amawasya ( considered somewhat inauspicious, though the Diwali the most popular Hindu festival is celebrated on Amavasya).

"Every astronaut will return to earth carrying invisible damage deep in their cells"--this was beautiful, caring, and bittersweet. Incredible writing.