Dear Lunatics,

If you’re like me, you have less hair on your head than you did last full moon.

All month I was pulling out tufts as NASA’s moon-bound Artemis 1 simply refused to launch.

Three times, NASA scrubbed the mission at the last moment due to an impressive variety of engine problems and fuel leaks.

Artemis 1’s SLS rocket runs on liquid hydrogen, which is notoriously problematic.

Many are calling for NASA to switch propellants to the more cooperative methane, which burns cooler and cleaner.

Even college students are harnessing its energy.

In 2017, the Purdue University chapter of SEDS (Students for the Exploration and Development of Space) became the first student team ever to fire a methane-powered rocket into the sky.

A methane-fueled rocket would certainly be an improvement over the early Apollo missions, whose Saturn V rocket was loaded with enough kerosene to fill an Olympic-sized swimming pool.

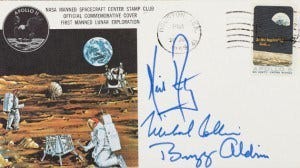

No wonder the Apollo 11 astronauts spent the month leading up to their launch autographing hundreds of postcards.

Lunar insurance didn’t—and still doesn’t—exist, and these cards (now worth up to $40,000 a piece) were the astronaut’s way of ensuring that their families would be financially secure should the worst happen.

To be fair, you can understand why NASA is so skittish about touching the match to Artemis 1.

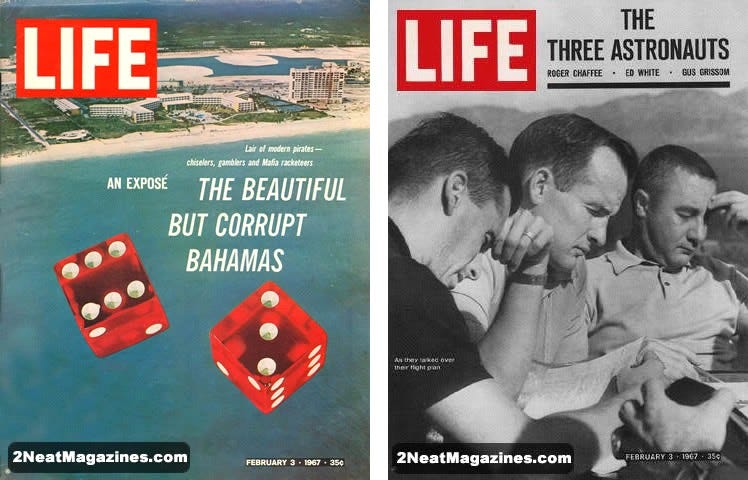

Fifty-five years ago, its older brother, Apollo 1, went up in flames during a ground test, burning the three astronauts inside.

When news broke of the Apollo 1 inferno, LIFE Magazine literally stopped its presses.

Their revised issue had a new main story (“Put Them High on the List of Men Who Count”) and a fresh cover—a black-and-white photo of the deceased astronauts huddled together, their brows knit as they talked over their flight plan before stepping into the capsule.

Here’s a strange fact.

Prior to the last-minute change, LIFE Magazine’s feature story that week was supposed to be "Fantastic Mission to Revoke Death,” an article about the first person to ever be cryogenically frozen for potential future revival.

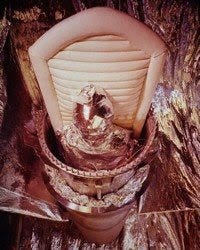

The man in question was James Bedford, a 73-year-old psychology professor who passed away from kidney cancer a few weeks earlier. Obeying his wishes, a doctor packed his body on ice while staff from the Cryonics Society of California dashed to his deathbedside. They arrived, drained his blood and replaced it with antifreeze, then brought his frigid corpse to Phoenix, where a cylinder brimming with liquid nitrogen was waiting.

Today, James Bedford is still resting in peace at -196 degrees Celsius, along with around 500 other cryonauts in scattered vats across the globe.

Will the technology ever be developed to resurrect these cadavers?

Most scientists are dubious.

“Even if you were defrosting the body with no damage to the tissues, the body will still be dead when you warm it up,” Dr. Matteo Cerri recently told NBC news.

Of course, that hasn’t deterred the nearly 2,000 people currently living who have signed up for the postmortem deep freeze.

They are betting that future humans will be able to accomplish what now seems impossible.

Even if the odds of revival are slim, they reason, isn’t a nonzero chance better than no chance at all?

Cryonics is a very different kind of life insurance—one that until this week I’d never truly considered.

(Apparently, in the cryo-world, this is called cryocrastination, and it’s endemic among those who have yet to make practical plans for their demise.)

I wonder: Would I feel safer moving through the world if I knew that in some salt mine in Kansas a frosty aluminum tank was reserved especially for me?

Not really.

If I did invest in immortality, I think I would paradoxically feel more fragile. I’d start to treat my body like glass. Because who wants to be resuscitated inside a mangled frame?

And I would be less geographically adventurous. No swimming out to that sandbar. No hiking the trail that winds through the woods.

The cryopreservation process must start within 15 minutes of the customer’s death.

Try not to die on a weekend, someone in the business once joked.

And then there’s the cost, which can run upwards of $200,000.

No wonder cryopreservation is the province of the well-to-do.

In fact, some of the cryopreserved stipulate that they only want to be thawed out when their investments are up.

In their minds, the only thing worse than being dead is being poor.

(If I were planning to be preserved, I would invest my entire portfolio in cryonics technology and await the fortuitous convergence.)

But there’s another reason why cryopioneers hire estate planners who specialize in safeguarding the assets of the frozen—namely, those dastardly heirs.

Who’s to say a tycoon’s great-great-great-grandchild won’t be as Machiavellian as his ice-bound ancestor?

How long would it take a crafty descendant to siphon the money from your trust, buy out the cryonics company holding your body, and cut the electricity?

It’s this same essential fear of the coming generations that is currently driving the development of cryosleep for interstellar travel.

At the moment, astronauts in space sleep a normal eight hours with their heads velcroed to their pillows.

But for voyages to Mars and beyond, astronauts will need to bed down in a long, chilly hibernation while AI robots steer the ship, rousing the crew from their slumber only in the event of an emergency.

Cryosleep is considered especially necessary for prolonged expeditions, those trips that will take several human life spans to complete.

Why not simply pack the spacecraft like Noah’s ark and let successive generations of space-born astronauts complete the expedition?

Well, the answer is obvious: lack of trust.

Scientists fear that children born as passengers will rebel against their parents.

As the aerospace engineer Jekan Thenga has said, the younger generations may lose their zeal for the mission.

At any rate, these were my thoughts about cryonics…until I stumbled upon the story of Max Li.

A robotics whiz and an aspiring aerospace engineer, Max earned grades high enough to get into his dream school—Purdue University—where he would have joined the SEDS team and helped send up methane-fueled rockets like Roman candles.

But a diagnosis of osteosarcoma scrubbed his launch into college.

He underwent six months of treatment—chemotherapy that might have broken his spirit if not for the presence of his mother, Shing, who quietly crocheted beautiful flowers and succulents in his hospital room. (Max’s doctor had told her that crocheting was a good way to relieve stress.)

After his treatment ended, Max, now outfitted with a prosthetic leg, enrolled at the University of California San Diego, promptly won entrance into that school’s chapter of SEDS, and joined the propulsion team to finally begin the experimental work on rocket fuel.

But just a few months into 2020, his cancer returned.

This time it was widespread and terminal.

Max reported feeling crushed with despair, sapped of all his energy and motivation.

The only thing he could bring himself to do was to make a scarf out of looped yarn for his mother.

Max had a sincere desire to evolve humanity into a space-faring civilization–a kind of species-wide insurance policy in case life on Earth becomes untenable.

But what could he do with such limited time?

Ever the engineer, Max looked to science for a solution.

He found cryopreservation.

He became especially interested in the developing technology of aldehyde-stabilized cryopreservation (ASC). Unlike the cruder cryonic procedures now on the market, ASC would preserve the so-called connectome—the comprehensive map of neural connections in your brain, that precise tangle of neurons that carries your long-term memories.

In the future, a brain solidified by ASC could be scanned, its infinitesimally small contours extracted as information and then uploaded into an artificial body.

Some object that this second version would not actually be you but rather a copy.

I’m not sure.

This new self may be made from different yarn, but the crochet pattern would be the same.

Surveying the field, Max became frustrated by the lack of resources invested in cryonics.

He believed that every terminal patient, especially children, should have the option to preserve their brains at death in a procedure that would happen in the hospital setting.

Just think about it.

Instead of diagnosing a young patient with an incurable disease, we could diagnose them with an as-yet incurable disease.

According to the website of Cryosuisse, “[C]ryonics attempts to function as an ambulance service through time.”

In this vision, “terminal” patients would be frozen and then reanimated once medical science had rendered their conditions curable.

Who wouldn’t support that?

A common bias against cryonics—one that I shared until a few days ago—is that it’s somehow unnatural, a final act of vanity by someone old and wealthy who can’t accept that there is a season for all things, a time for planting and a time for harvest.

But doesn’t someone like Max deserve to experience all the seasons of a human life—even if that requires a late spring frost that lasts five hundred years?

As his condition worsened, Max tried to persuade his mother to join him in his cryopreservation plans.

But she declined.

As she wrote to me in an email this week: “I am old, have done my part to explore and [am] tired, so I am fine to be gone forever instead of getting revived.”

Even so, she fully supported her son’s dreams of preserving his brain and awakening in a future where he could traverse the solar system, shaking out moondust from his boots.

Max passed away in March.

With the ASC process not yet ready for use, he considered trying a commercial cryonics company, but ultimately decided that their method was unlikely to preserve the brain.

“So sadly he gave up at the end,” his mother wrote.

I then asked his mother Shing, as delicately as possible, the following hypothetical: If her and Max’s brains were preserved, would that in any way change the sorrow she feels now?

The thought of a reunion would be exciting, she said. “But it [would be] too far in the future to subside my grief in this life.”

It’s easy to be cynical about the future.

To roll our eyes at the hapless Artemis 1.

To dismiss cryonics as a doomed, science-fictional dream.

To assume that the generations that follow us will be so spoiled that they won’t even care about preserving humanity.

But Max has given me faith.

Instead of freezing his body, he used his death to light a fire under the scientific community. That fuel still burns today, and his efforts may well result—far down the line—in the survival of others who receive similar terminal diagnoses.

For Shing, the scarf that Max knit is a symbol of his strength and caring.

It was his way of giving her something tangible to remember him by.

Because despite facing his death—a death with no insurance policy—Max never stopped thinking about the future and caring for those around him.

He never lost his zeal for the mission.

See you on the Hunter’s Moon.

—WD

A note to readers: I thought long and hard about whether I had the right to tell Max Li’s story in this newsletter. Ultimately, I did so for three reasons: 1.) As a champion for cryopreservation science, Max used his compelling life story as a part of his public advocacy. 2.) His gracious mother assured me that Max would want his story shared as widely as possible. 3.) I knew that at the end of this newsletter I could link to the following interviews so readers would hear Max’s story told in his OWN voice.

I am sure you will find him as remarkable a person as I do.

Thank you for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to this newsletter, which is as free as looking at the Moon.

And please consider sharing this post with some of your fellow Earthlings 🚀.

Thank you for allowing me to discover the story of an amazing young man.

May Max rest in peace