Dear Lunatics,

I missed the solar eclipse.

Every morning, the sun javelins through my east-facing bedroom windows.

But in Massachusetts, this rare, eerie event took place in the late afternoon, when it couldn’t be seen through my window frame. (Believe me, I squashed my face against the glass in the effort.)

I was so frustrated, I could’ve climbed the walls—though I suppose if I were capable of that, I could’ve made it to the other side of the house.

It’s not just that I won’t see another total solar eclipse in my lifetime.

Solar eclipses themselves are a miracle.

By a freakish cosmic coincidence, the Moon is 400 times smaller than the Sun and 400 times closer to the Earth, making the Moon and the Sun appear roughly the same size in the sky and allowing the occasional perfectly fitted solar eclipse.

The chances of our bespoke Moon-Sun relationship are so slim that some fringe thinkers believe the Moon is artificial.

In Who Built the Moon?, Christopher Knight and Alan Butler make the case that the Moon—a satellite without which intelligent life would not have flourished on Earth—was intentionally created.

The only question, in their minds, is who built it?

Their suggested answer: we did.

Or at least, we will.

Future humans will travel back in time to construct the Moon and slide it into its orbit. They will do this so that the Earth develops the necessary conditions for humans to evolve 4.6 billion years later and then, at some distant point, travel back in time again to construct the Moon.

They are proposing a time loop, an explanation most of us instinctively balk at.

The trouble with time loops is the potential paradoxes they give birth to, the most well-known being the so-called “grandfather paradox.”

The grandfather paradox seems to have made its first appearance in the December 1931 issue of Astounding Stories, in which a 17-year-old reader wrote a letter to the editor:

There is only one kind of Science Fiction story that I dislike, and that is the so-called time-traveling. It doesn't seem logical to me. For example: supposing a man had a grudge against his grandfather, who is now dead. He could hop in his machine and go back to the year that his grandfather was a young man and murder him. And if he did this how could the revenger be born? I think the whole thing is the "bunk."

The grandfather paradox has become a popular argument by those who dismiss the possibility of time travel and argue that backpaddling through the river of time would lead to self-contradictory situations.

However, in the mid-1980s, the Russian physicist Igor Novikov proposed a solution: closed time loops.

If you travel backward within such a time loop, you will not be able to shoot your grandfather. Maybe your gun will jam. Maybe the bullet will graze his shoulder and you’ll finally know the origin of the scar you’d always assumed he got in the war. Or maybe, because you’re used to your grandfather being old and fragile, you’ll underestimate his strength and he’ll wrestle the gun away and shoot you.

“It’s so simple. So obvious,” Novikov said. You can travel back in time, but nature will not allow you to rewrite history. “What has happened has happened. It cannot be changed.”

Suddenly, time traveling sounds incredibly frustrating, as you would be stuck in a world you cannot meaningfully alter.

When asked whether this violates the time traveler’s free will, Novikov pointed out that our free will is always restrained by nature.

“I can have a free will to walk along this wall without special equipment,” he said, gesturing to the ceiling. “It’s my free will. Can I do that? No, I can't. Why? Because of a law of physics. Because of the law of gravity. It's forbidden”1

So all the grandfathers out there can take a deep sigh of relief.

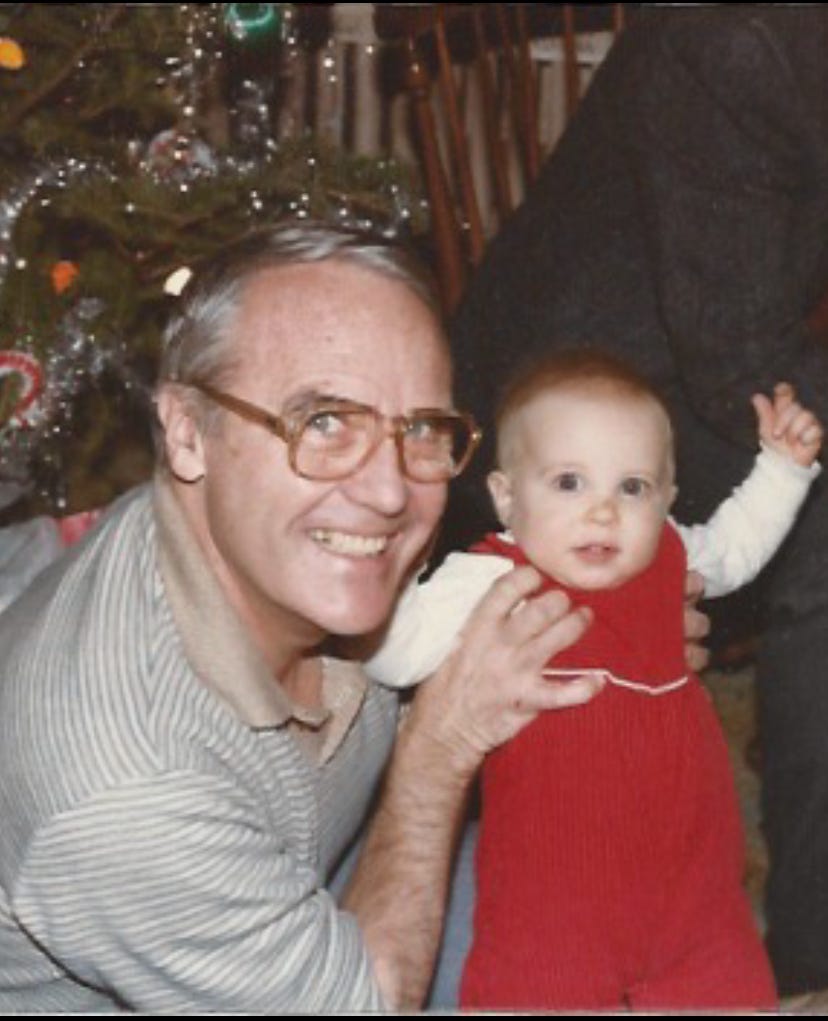

I was in the room when my grandfather died.

The whole family was crowded around the metal bars of his hospital bed when his ventilator was removed.

I found and squeezed his foot under white linens as his breathing waned.

“Can he hear us?” someone asked.

“Maybe,” a nurse said.

One by one, we all voiced some form of goodbye.

Although my family only lived fifteen minutes away, my grandfather rarely visited us. Every birthday, he’d drop a card in my mailbox without ringing the bell. I’d watch through a window as he raced back to his running car to avoid the possibility of a social interaction.

He was in no way cruel—the opposite, in fact. He was just reticent, even with his family. We had few one-on-one conversations.

Unless you count the phone calls.

In the year before his death, my grandfather began to ring me at odd hours—sometimes late at night. Without so much as a hello, he’d launch into a convoluted math problem.

The sum of the exterior angles of a polygon…

The compound interest on a theoretical mortgage…

I imagined him sitting up against his headboard, the bedside lamp casting a halo of light over a legal pad lying on his lap covered in scratched-out equations.

I’d locate a pen and solve his problem—usually on nearby scraps of paper, once on my forearm. Then I’d walk him through it. Often I’d be halfway through the explanation when the math would come rushing back to him and he’d hang up without a word.

My grandfather was a math whiz who, as an 18-year-old soldier in World War II, taught trigonometry at West Point. Along with his intolerance to gluten, I inherited his facility with numbers, which is why he called me when the formulas and proofs in his mind began to dim.

Growing up, I never felt as though I had to learn math. It felt more like remembering something I already knew. I would turn the textbook pages with an uncanny sense of déjà vu and endure the torture of math class the way you would endure being stuck in a time loop, repeating algebra class over and over again.

I recognize this inheritance in my nephew, in his leaps of understanding as I present him with new problems, and in his precocious deployment of the word “Duh” when the problems are not hard enough.

Was it the same for my grandfather? Is this how he felt as a math pupil?

I’ll never know. He never spoke to me about our shared passion.

My Dad thinks he would’ve made a good priest, given his faith, charity work, and preference for quiet and solitude. Instead, he opted for family life and my father was born in 1953.

(To enact the grandfather paradox, I wouldn’t have to shoot my grandfather; I’d just have to go back in time and nudge him toward the clergy.)

Coincidentally, 1953 was an interesting year for time travel.

It was the year when Jack Sarfatti says he received a telephone call from the future.

Dr. Sarfatti is a theoretical physicist who studied under Werner Heisenberg and whose remarkable early career is documented in David Kaiser’s book, “How the Hippies Saved Physics.”

But on a warm summer night in Flatbush Brooklyn in 1953, he was just a 13-year-old science prodigy who was home alone when the phone rang.

On the other line was a metallic artificial voice—the same one Stephen Hawking would use decades later. It identified itself as a computer onboard a spacecraft that had traveled from the future.

As Sarfatti recalled in a recent interview, the computer claimed to be recruiting 400 receptive young minds to participate in a technological project that would ultimately lead toward its own creation.

A time loop, in other words.

When the boy agreed, the metallic voice told him he would begin to meet “the others” in 20 years.

And indeed, in 1973, Sarfatti was invited to the Stanford Research Institute, where he met Edgar Mitchell (the 6th person to walk on the Moon), as well as Hal Puthoff and Russell Targ, physicists and parapsychologists who told him they believed flying saucers were time machines from the future.

Dr. Sarfatti, who often speaks about himself in the third person, has a healthy regard for his own genius. I suppose it would be difficult not to think highly of yourself if you’d been handpicked by time-traveling AI to construct the future.

He doesn’t share this high regard for many others in his field. He tends to label his peers as “schmucks” who don’t know anything.

So it was with some trepidation that I reached out to him by email, hoping that he would answer a question his story had raised—one that the interviewer did not pursue.

To his credit, Dr. Sarfatti did respond, though there was no hello.

“I have nothing to add to this,” he wrote, before linking to the interview and an encyclopedia entry on Igor Novikov.

“I have nothing new to say on both these topics.”

There was no goodbye.

If I’d had the chance, I would have asked Dr. Sarfatti about a particular moment in his story. During that mysterious 1953 phone call, the computer asked him in its metallic voice whether or not he wanted to join its cryptic mission.

“It said I had to now tell them, out of my own free will, if I wanted to participate in this project,” Sarfatti recalled. “And I'm thinking to myself, no…But then I feel like an electric shock go from the base of my spine to the back of my head here…an electrical feeling, and I hear myself saying, yes.”

So did the 13-year-old boy actually have a choice? Or was his free will overpowered by the needs of the time loop?

The more I think about Novikov’s time loops, the more I question free will.

If the actions of a time traveler from the future are constrained by nature, the actions of a non-time traveler are equally constrained—only the non-time traveler isn’t aware of it. They are both fixed within the groove of the same time loop.

The only difference between the two would be the time traveler’s impotent foreknowledge of the future and the non-time traveler's obliviousness to what’s coming.

Usually, the suggestion that free will is an illusion irks me, and I feel the urge to do something unpredictable and utterly out-of-character, like smashing a vase or getting a start on this newsletter before the full moon is already cresting the tree line.

But lately, I’ve been wondering if there wouldn’t be a consolation

Maybe my grandfather was interested in me but couldn’t act on it.

Maybe he was constrained by a time loop, a restriction stronger than any gravitational orbit and tighter than any priest’s collar.

Because if he had nurtured my instinct for numbers, I have no doubt I would’ve become a mathematician.

And then I never would have written this.

And you wouldn’t be reading it.

Today, Jack Sarfatti’s concept of a “weightless warp-drive” is informing the production of a fusion device at Lawrence Livermore National Labs, which, if successfully constructed, may bring us one step closer to developing the means of propulsion exhibited by recently filmed UAPs.

Igor Novikov is continuing to bend time by still working as a theoretical astrophysicist despite being 88 years old.

Who Built the Moon? author Alan Butler is combing through the history books to identify possible time travelers. (Leonardo da Vinci, Sir Isaac Newton, and Thomas Jefferson are major suspects.)

Several miles away, my nephew is tossing in his sleep or else lying awake, multiplying sheep.

And my grandfather is lying in a grave, next to his wife, the moonlight tracing its pale fingers over their tombstones, their birth and death dates set in stone.

Meanwhile, I’m sitting here, as fate or folly dictates, writing another dispatch while the Moon winks at me through thick branches, flashing now and then like a monocle catching the light.

At my grandfather’s wake, I spent a long time kneeling before his casket, not only praying but trying to figure out why he looked so strange. Eventually, I realized it was the first time I’d seen him without his glasses.

I remember thinking, he’s at rest now. And without his phone calls, maybe I’ll get some rest, too.

But I was wrong.

My grandfather still calls me in the middle of the night.

Same lack of pleasantries.

Same tone of panicked bewilderment in his voice.

Only now, the math problems that he poses are beyond me.

And in my dreams, I can never find a pen.

See you on the Flower Moon!

-WD

How do you write this? Awestruck by every turn it takes from the beginning to this end. 💜 Not tempted to tamper with the past because I am grateful that one has found their way towards writing.

Another marvelous dispatch. Will Dowd’s posts seem lit from within by the mysterious glow of the penumbra. A magical essayist and an artist of the tangential finesse. Thank you!