Dear Lunatics,

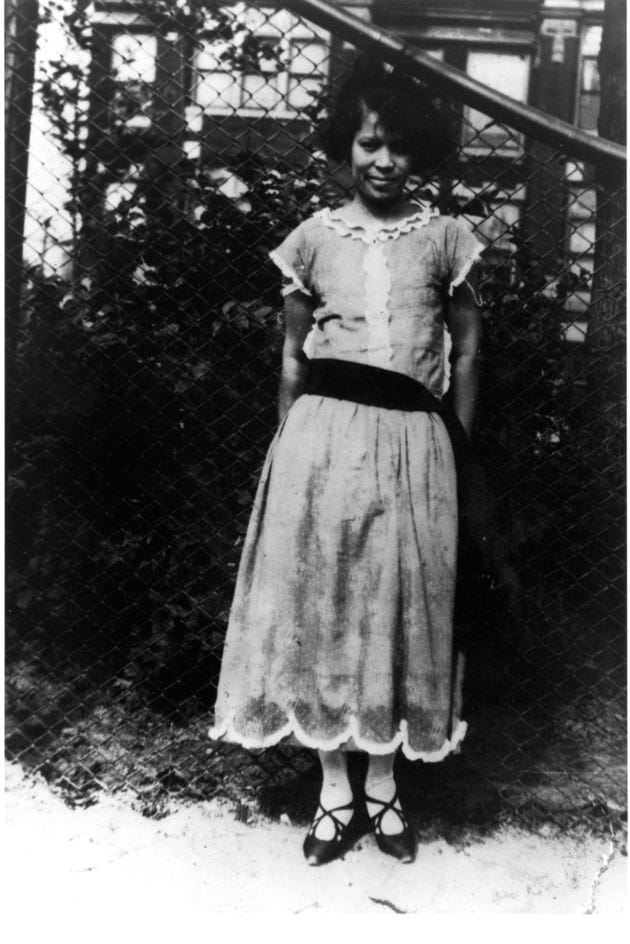

When she was young, Zora Neale Hurston got into an argument with her friend over whom the Moon preferred.

Hurston bragged that whenever she played in the moonlight, the Moon would follow her, turning its bright face in which ever direction she ran.

But her friend claimed the Moon didn’t care about Zora at all; it was too busy following her.

To settle the point, the two girls stood back-to-back and raced in opposite directions.

Both claimed victory.

In her autobiography, Dust Tracks on a Road, Hurston later recalled what happened next:

“When the other children found out what the quarrel was about, they laughed it off. They told me the moon always followed them. The unfaithfulness of the moon hurt me deeply.”1

The Moon’s betrayal may have dented Hurston’s youthful niavety, but her childhood didn’t truly end until one hot summer day when she was seven.

After playing a practical joke at home, Hurston went searching for a hiding place—somewhere she could stay until things simmered down.

She passed a strawberry patch and came upon the shady porch of a vacant house. There, she lay down and fell into a strange half-sleep.

Twelve scenes paraded before her mind’s eye:

“There was no continuity as in an average dream. Just disconnected scene after scene with blank spaces in between. I knew that they were all true, a preview of things to come, and my soul writhed in agony and shrunk away. But I knew that there was no shrinking. These things had to be.”

Hurston awoke and descended the porch stairs.

She staggered under the weight of what she now knew lay on the dusty road ahead:

“I knew that I would be an orphan and homeless. I knew that while I was still helpless, that the comforting circle of my family would be broken... I would hurry to catch a train, with doubts and fears driving me and seek solace in a place and fail to find it when I arrived, then cross many tracks to board the train again. I knew that a house, a shot-gun built house that needed a new coat of white paint, held torture for me, but I must go. I saw deep love betrayed… And last of all, I would come to a big house. Two women waited there for me. I could not see their faces, but I knew one to be young and one to be old. One of them was arranging some queer-shaped flowers such as I had never seen. When I had come to these women, then I would be at the end of my pilgrimage, but not the end of my life. Then I would know peace and love and what goes with those things, and not before.”

Hurston never told anyone about her prophetic visions—not even her mother, who’d always indulged her imaginative daughter’s fanciful tales.

Young Zora would dash home from playing outside and boast that she’d walked across the surface of a lake or climbed up the tail of a talking tropical bird.

Her grandmother would be enraged by these “lies.” “Grab her!” she’d yell. “Wring her coat tails over her head and wear out a handful of peach hickories on her back-side!”

Yet her mother never tried to break her spirit: “Mama exhorted her children at every opportunity to ‘jump at de sun.’ We might not land on the sun, but at least we would get off the ground.”

But after the day of visions, Hurston was never the same.

“Oh, how I cried out to be just as everybody else! …True, I played, fought and studied with other children, but always I stood apart… A cosmic loneliness was my shadow.”

Any innocence Hurston had left was extinguished on September 18th, 1904.

For months, she had been watching helplessly as her mother’s health deteriorated. Then, one late summer evening, Death, which Hurston had sensed lingering in their yard, finally stooped to enter the family home.

Two weeks later, Hurston was driven to catch a midnight train to Jacksonville, where her older sister would ostensibly look after her.

“As my brother Dick drove the mile with me that night, we approached the curve in the road that skirts Lake Catherine, and suddenly I saw the first picture of my visions. I had seen myself upon that curve at night leaving the village home, bowed down with grief that was more than common. As it all flashed back to me, I started violently for a minute, then I moved closer beside Dick as if he could shield me from those others that were to come.”

In the years to come, Hurston’s visions all came to pass, proceeding, like a dozen slides in a stereoscope, in the precise order they had come to her that day on the porch by the strawberry patch.

At last, when the twelfth and final vision was behind her, Hurston was free—free from the grip of fate and ready to make a new life.

She was living in Baltimore. She was 26 years old. She had no education.

So Hurston fell back on her oldest, greatest talent: lying.

According to Maryland law, "all colored youths between six and twenty years of age" were provided free admission to public schools.

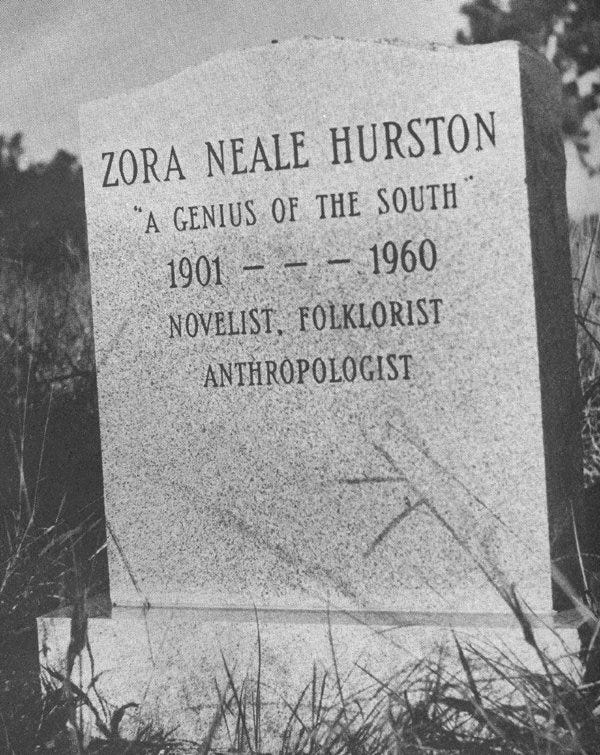

So Hurston simply decided she had been born in 1901 rather than 1891, a lie she maintained so diligently and for so long that even her headstone shaves away her first decade of life.

By transforming herself into a secretly 26-year-old high school student, Hurston began her journey to becoming the first Black student to attend Barnard College.

At Barnard, she studied anthropology, making trips to her native South to collect folktales, which the storytellers colloquially refered to as “lies.”

During her expeditions, the pistol-carrying Hurston often slept in her car when she couldn’t find a hotel that accepted Black patrons.

“Sometimes, I feel discriminated against,” she wrote, “but it does not make me angry. It merely astonishes me. How can any deny themselves the pleasure of my company?”

Along with collections of African American folklore, Hurston began to write her own lies. The grandest lies of all.

Novels.

Unfortunately, the world was not as indulgent as her mother regarding her lies.

Her third novel, Their Eyes Were Watching God, was jeered by prominent members of the Harlem Renaissance at the time of its publication.

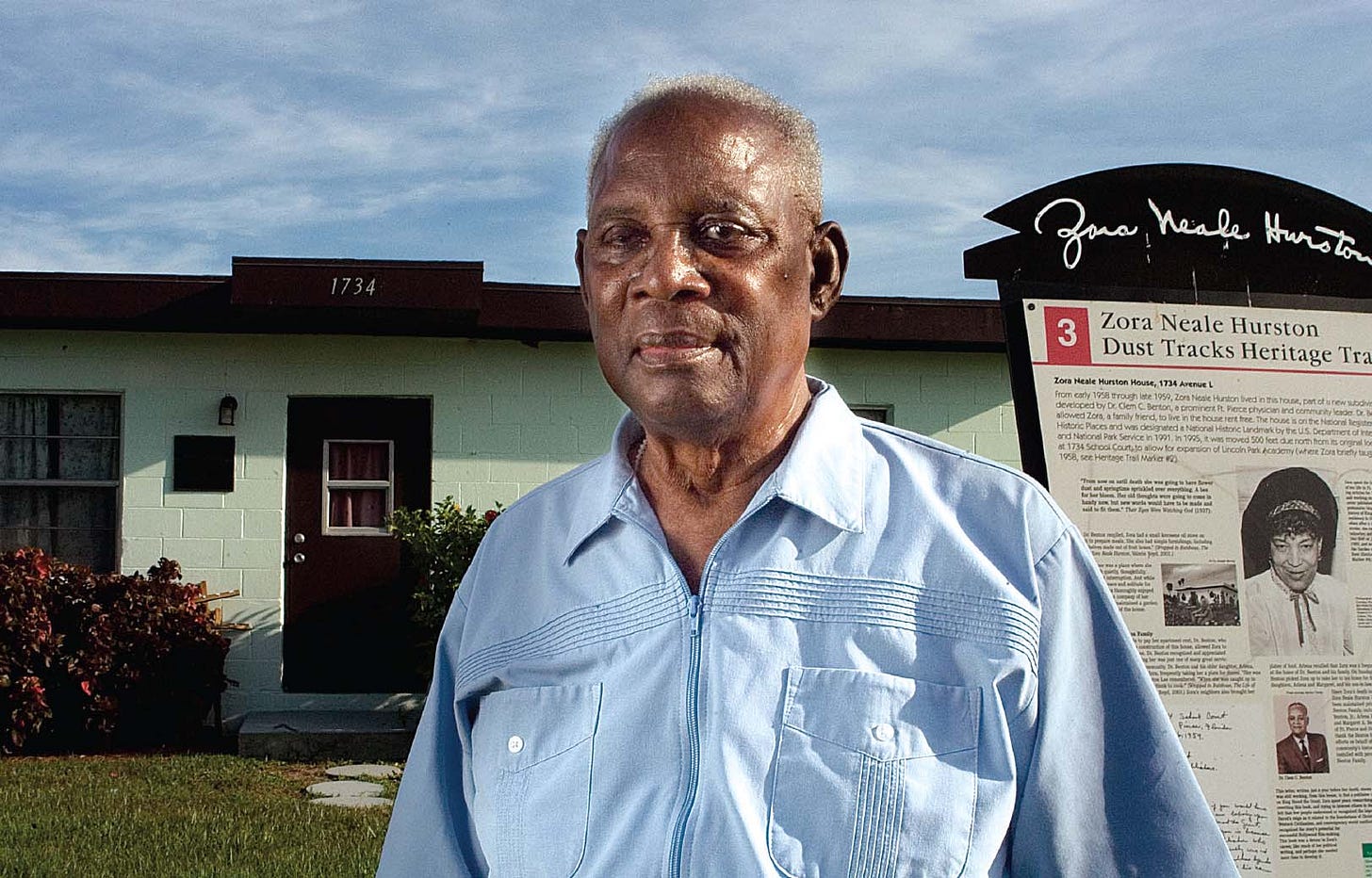

She made little money from her books and spent the last three years of her life residing in a 28-square-foot cinderblock cottage in Fort Pierce, Florida, where she eked out a living by writing for a community newspaper and substitute teaching.

Her only belongings at this time were a kerosene lamp, a typewriter that she temporarily pawned whenever her money tin was empty, and giant stacks of paper—a biography of King Herod she’d been writing for fifteen years.

By then, all of her books were out of print.

Yet while the literary world may have discarded her, the Fort Pierce community embraced her.

The local physician Clem C. Benton, who owned Hurston’s house, allowed her to live there rent-free.

I spoke to Dr. Benton’s daughter, Arlena Lee, who remembers Hurston sitting on the front stoop in the evenings, reading to the neighborhood children, chatting with the adults, and waiting hopefully for someone to bring her a plate of food.

“She just would not cook,” Mrs. Lee told me, laughing. Hurston would often forget to eat because she was so absorbed in her manuscript. “She was a nice person,” Mrs. Lee assured me, “but she was a writer.”

A series of strokes landed Hurston in the St. Lucie Welfare Home, where she died on January 28, 1960.

“I’m not materialistic,” Hurston had once written to an ex-husband. “If I happen to die without money, somebody will bury me.”

This was another prophecy that came true.

The Fort Pierce community raised money for a funeral—Arlena Lee remembers at least 100 mourners in attendance—and a burial in the nearby Garden of Heavenly Rest cemetery.

A headstone wasn’t erected until 13 years later when the author Alice Walker made a pilgrimage to the unmarked grave, which was by then concealed under Florida weeds.

Hurston died without an heir. Her three marriages had been brief and unsatisfying. (“Who had canceled the well-advertised tour of the moon?” the discontented bride wanted to know after her first nuptials.)

Her true love had always been her work.

With no children or nearby relatives, the nursing home ordered all of Hurston’s possessions destroyed.

One evening, behind her cottage, a hired yardman dumped Hurston’s letters, photographs, unpublished manuscripts, and meager belongings into an oil drum and set them ablaze.

Driving home from work, a sheriff's deputy happened to see a curl of smoke in the distance. Curiosity prevailed and he decided to investigate.

Behind the small, mint green house, he found the yardman beside the burning barrel, idly watching a dead woman’s possessions turn to ash.

The deputy leapt into action. He grabbed a garden hose, turned on the spigot, and doused the flames.

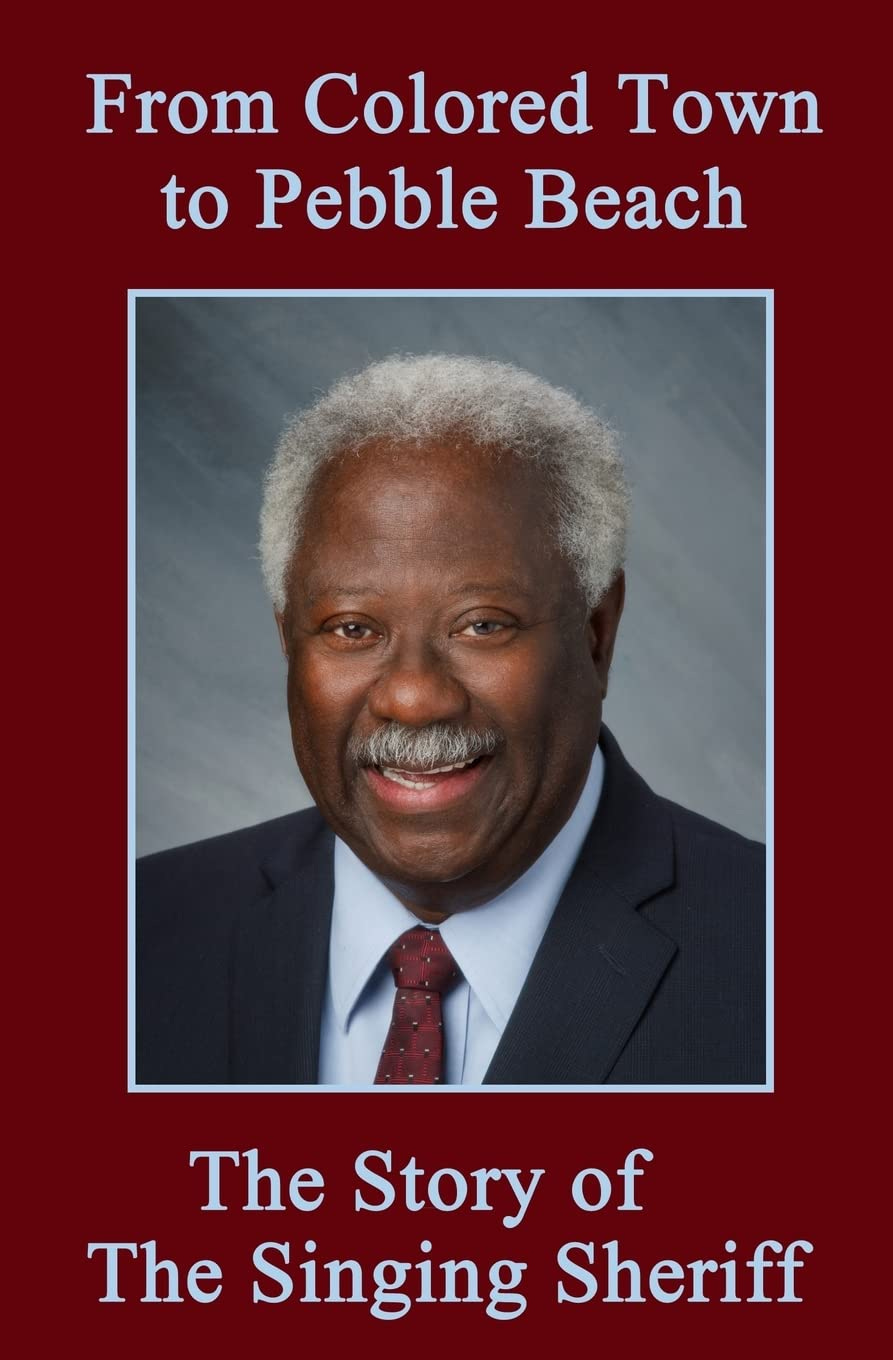

Patrick DuVal was the first Black sheriff’s deputy in St. Lucie County history, a position that had attracted threatening phone calls from members of the KKK, who promised to kidnap his children and tar and feather him.

DuVal, who had read one of Hurston’s novels, understood that her belongings were valuable.

Because of his fast actions, he ensured the author’s charred, waterlogged papers were saved and donated to the University of Florida, where they remain today. Hurston’s The Life of Herod the Great, snatched from the flames, is finally set to be published in January 2025.

I hoped to speak with Pat DuVal, who’s been called an “archival superhero” by the University of Florida.

Unfortunately, I discovered that he passed away at the age of 100 in July 2020, a victim of the coronavirus pandemic.

Luckily, I was able to connect on the phone with his son, Pat DuVal Jr., who was recovering from a knee operation in his home in Carmel, California.

“I felt sorry for her,” DuVal Jr. told me of Hurston, who served as a substitute teacher at his high school. “I can still see her standing in the classroom doorway, looking unkempt.”

I can almost hear DuVal wince at the memory, his voice filling with compassion. “She wore the same clothes every day,” he told me. “She was poor.”

Duval Jr.’s life has been just as groundbreaking as his father’s, only more star-studded. After a stint in the U.S. Army that took him to Panama, he became the first Black deputy of Monterey County, befriending, among other celebrities living in the area, Clint Eastwood, who cast him in three movies.

Known as the “Singing Sheriff,” DuVal Jr. has performed with the Monterey Symphony and belted out the national anthem for the San Francisco Giants and Houston Rockets.

Duval Jr. committed his life to paper in a 2014 autobiography, From Colored Town to Pebble Beach: The Story of the Singing Sheriff.

The book was not his idea.

He’d been spurred on by Maya Angelou.

“But I can hardly write tickets,” he’d protested.

“Shut up,” Angelou had said firmly. “You just write down all your experiences.”

Hurston would have given DuVal the same advice:

If writers were too wise, perhaps no books would get written at all. It might be better to ask yourself ‘Why?’ afterwards than before. Anyway, the force from somewhere in Space, which commands you to write in the first place, gives you no choice. You take up the pen when you are told, and write what is commanded.

But don’t fool yourself, she may have also warned. Just because your writing is inspired by a cosmic force does not mean it will endure.

Hurston never expected immortality, neither personal nor literary.

She had made her peace with the fact that she and her novels, along with the Earth itself, were destined to burn up on the blistering rim of our dying Sun, then drift in perpetuity through the dark expanse of outer space like ashes scattered on a windy night.

She was so resigned to fate that she refused to pray, which she considered “an attempt to avoid, by trickery, the rules of the game as laid down.”

“I do not expect God to single me out and grant me advantages over my fellow men,” she wrote.

The final chapters of Hurston’s autobiography read like one long rebuke to the naive young girl who’d once been foolish enough to think she was the recipient of the Moon’s special affection.

Today, Hurston’s books are back in print and this “Genius of the South” is read by millions.

Each year, thousands flock to the ZORA! Festival, which is held in Eatonville—a town the young Hurston watched disappear behind a curve in the road in fulfillment of her first vision.

Lying on that porch by the strawberry patch, it’s a pity she hadn’t had a thirteenth vision, a glimpse of her hometown more than 60 years after she would become “whirling rubble in space.”

Hurston was right, of course—someday, the Sun will swallow all.

There’s no point in wringing one’s hands or denying the inevitable.

Like the rest of us, her bones and her books are destined for the flame…

but not just yet.

See you on the Buck Moon!

—WD

All literary quotations from Zora Neale Hurston’s Dust Tracks on a Road: An Autobiography (1942)

We need more archival heroes in this world! I loved this. Thank you Will.

I think the Moon did follow Zora, and that we have her beautiful, unforgettable writing in this world is proof. 🌙 So so beautiful Will—the chance of someone caring for one others work, for recognizing it, is an act that echoes across the distances. Thankful for Pat Duval, his son, the ways that Zora’s magnificence is still known—and reflected. And thankful you share this all with us. 💜