Dear Lunatics,

One week ago, four volunteers stumbled into a 1,700-square-foot red sandbox. The door to their domed habitat, which was designed to simulate a dwelling on Mars, was locked behind them. The door will remain locked for the next 378 days.

Conducted at the Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas, this NASA experiment will subject the volunteers to various stressors—resource constraints, malfunctioning equipment, communications breakdowns—all to study the physical and, more importantly, psychological toll that a long season spent on Mars might take on a human being.

Space psychology has been an area of intense research for over half a century, but the field is heating up now that astronauts could face long-term (or even permanent) voyages into the solar system.

Steps have already been taken to keep the inhabitants of the International Space Station from going stir-crazy (or stirring alcoholic drinks like crazy). The ISS currently features a treadmill and a vegetable patch for gardening. Looking ahead, NASA is funding a technology called ANSIBLE that could allow astronauts to explore nature and share prerecorded meals with their families via virtual reality goggles.

Still, for all its stress-relieving outlets, the most popular activity for astronauts on the ISS is to hover in the Cupola, a dome-shaped module with seven windows, where they can watch the Earth below. They can see the Sun rise and set on their home planet 16 times in one day.

Apparently, the view is mesmerizing.

Space psychologists have named the experience the “overview effect.”

According to Dr. Kelley Slack, an organizational psychologist who worked at NASA for 20 years in the Behavioral Health and Performance group:

The overview effect has to do with a sense of connectedness, awe and a feeling of greater purpose astronauts feel as they're looking at Earth and seeing the entire thing. Astronauts talk about a feeling of protectiveness or sense of responsibility.1

But what will happen to Mars-bound astronauts who, for the majority of their three-year trip, will only be able to see the Earth as a pinprick in the distance, if at all?

Or to future lunar astronauts who take up residence on bases on the far side of the Moon?

To address my concerns about the psychological effects of the so-called “Earth out of view” phenomenon, I decided to reach out to Dr. Slack by phone.

“It is a thing that NASA, as well as other space agencies, are thinking about,” she told me. “But there’s no way to test it.”

A proposal to cover the ISS windows and see how the tenants react was rejected.

I suggested that lunar colonists might feel grounded, even if stuck on the dark side, by the familiarity of the Moon and the intuitive knowledge that at all times people on Earth are looking up at their floating rock. But the aspiring Martians wouldn’t have this same connective tissue.

“It’s a scary thought,” Dr. Slack said. “What happens when they feel untethered? How will we keep them sane, especially with the 20-minute communication delay with Mission Control?”

Throughout my discussion with Dr. Slack, who served as a member of the astronaut selection panel, the theme of balance kept arising.

Suitable candidates should score neither too low nor too high on any of the “Big Five” personality traits—extroversion, agreeableness, openness, conscientiousness, and neuroticism. After all, it would be just as unbearable to live cheek-by-jowl with an irrepressible extrovert as an inveterate introvert.

This Goldilocks mentality applies to assembling a crew as well. It’s been noted that small groups working in isolated, confined spaces, such as Antarctic research bases, tend to develop their own cultures, including in-jokes and private references. This is natural and, to a degree, healthy. But you don’t want the group to become too close, which could risk the development of an “us vs. them” attitude toward Mission Control.

The goal is to avoid both internal schism and external mutiny.

Dr. Slack sometimes looks longingly at the testing methods employed by other countries—methods that NASA doesn’t allow.

For example, during one selection round, the Canadians took inspiration from a military scenario in which a group on a sinking helicopter has to decide whether to stay aboard or bail out.

“Our lawyers won’t even let us get our applicants a couple of feet off the ground,” Dr. Slack told me.

NASA’s nerves are understandable; the agency invests millions in its astronauts.

Yet some of the testing limitations are more cultural than legalistic. It’s hard to imagine the American government indulging in the Japanese origami test.

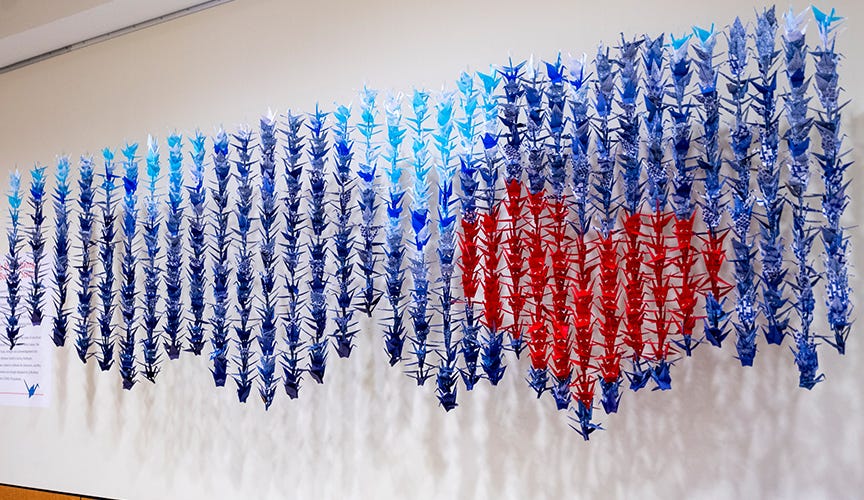

The Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency crams its prospective astronauts together into a dismal, greenish-grey room for five days and charges them with the task of assembling one thousand miniature paper cranes each.

The “One Thousand Cranes” test was devised by JAXA’s chief medical officer, Shoichi Tachibana.

According to Japanese legend, cranes live one thousand years, and therefore a person who folds a thousand cranes will be afforded good health and a long lifespan. (One thousand cranes, strung on threads, are often gifted to patients in hospitals.)

According to Dr. Slack, the origami task measures perseverance (astronauts spend much of their time doing relatively rote work such as conducting experiments and mending the spacecraft), and it allows psychologists to observe an applicant’s attitude.

Do they procrastinate?

And most importantly, does the quality of their cranes change over time?

"Deterioration of accuracy shows impatience under stress," JAXA psychologist Natsuhiko Inoue said.2

I feel sympathy for those who have failed to achieve their childhood dream due to a sloppily folded piece of rice paper.

Space psychology must have its limits, right?

For example, there’s one thing no space psychologist can predict: how susceptible a potential astronaut will be to space sickness—the nuclear cousin of motion sickness.

If you’ve never heard of the vestibular system, count yourself blessed.

Nestled in the inner ear, the vestibular apparatus includes membranous sacs, semicircular canals, tufts of sensory hair cells, and calcium crystals that bob in gelatinous fluid.

Our vestibular system is crucial to our sense of balance and bodily movement, and much like the inner workings of a space shuttle, you only become aware of it when something goes wrong.

And when humans leave Earth, the vestibular system decides that something has indeed gone very wrong.

Without the customary pull of Earth’s gravity, astronauts can experience a sensory upheaval leading to “orientation illusions, vertigo, dizziness, problems focusing on and tracking visual objects.”3

They can also experience space sickness.

The symptoms of space sickness range from queasy disorientation to furious vomiting. They typically last for 2 to 4 days, which is why extra-vehicular activities are not scheduled for the first few days of any mission. (Vomiting in a space suit can be fatal.)

Predicting ahead of time which astronaut candidates will suffer space sickness has proven to be impossible.

“Someone who gets car sick all the time can be fine in space—or the opposite,” the veteran astronaut Steven Smith has said. “I’m fine in cars and on roller coasters, but space is a different matter.”4

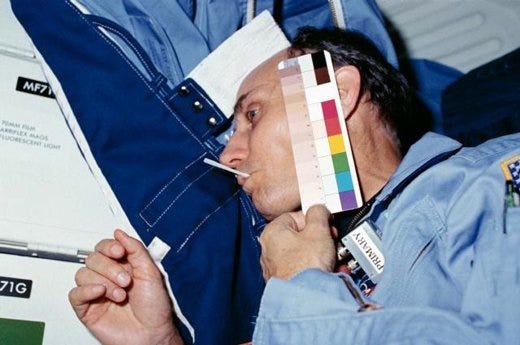

NASA has tried to prepare its trainees by sending them up on the so-called “Vomit Comet.” This aircraft makes parabolic flights, ascending and descending in a wavelike pattern, which gives those on board brief tastes of weightlessness.

Yet even those who keep down their lunch during this test may find themselves green around the gills when actually in space.

In the course of his four shuttle flights, Steven Smith calculates that he threw up approximately 100 times.

You have to admire Smith for getting back on that roller coaster four times, especially considering the singular horror of projectile vomiting in a metal tube where “up” and “down” have no meaning.

But Smith’s tribulations are relatively minor when measured on the “Garn scale.”

I’ll explain.

In 1985, a Utah senator overseeing NASA’s budget joked that if he did not get a spot on the next space shuttle flight, the agency wouldn’t get another cent.

The Senator was Jake Garn and, as it turns out, he wasn’t actually joking.

Over the protestations of astronauts who’d been waiting on deck for more than a decade, Garn was given a seat on the next shuttle flight.

It took off from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida on April 12, 1985 and traveled over 2.5 million miles in 108 Earth orbits.

The trip did not go well for Senator Garn.

The man experienced the worst case of space sickness ever recorded.

As astronaut-trainer Robert Stevenson recalled:

Jake Garn was sick…he has made a mark in the Astronaut Corps because he represents the maximum level of space sickness that anyone can ever attain, and so the mark of being totally sick and totally incompetent is one Garn. Most guys will get maybe to a tenth Garn if that high.5

Of course, even a tenth of a Garn is pretty bad.

While you can safely pop a pill to combat seasickness on a whale watch, astronauts can’t risk being sedated. And so, for decades, the US and Russia have been seeking a non-pharmacological treatment for space sickness.

The solution they’ve developed is OculoStim-CM, a computerized system that uses virtual reality goggles to exercise the astronaut’s vestibular function pre-flight as well as treat the symptoms they experience while in space.

I’ve used a very similar device.

Ever since a bout of meningitis scrambled my vestibular system five years ago, I might as well be living on the ISS.

My cluttered room, where I’m holed up, is perpetually revolving at various speeds. My bed, my desk lamp, my fishbowl—in fact, everything in my visual field—floats around unsteadily.

Nothing is tied down by gravity anymore.

Not even I am.

As I cross the room, I sometimes have to hold onto nearby surfaces as though I’m on a spacewalk and might drift away.

Along with trying every other possible remedy, I’ve spent hours with VR goggles strapped to my face, lying on my bedroom floor while visually rolling through the insides of a virtual disco ball.

The goal of the VR treatment is desensitization. After a while, the Mission Control in my inner ear was supposed to stop panicking and reacclimate to visuospatial signals.

But it didn’t work. I remain at a full one on the Garn scale. And I still spend most of my time shut up in my bedroom as though training for pod life on Mars.

There’s no hydroponic garden in here.

Nor a treadmill.

Nor a Cupola where I can hover, watching the Earth wheel beneath me.

All I have is a window to stand at and a full moon that fills it once a month.

I do get the overview effect, albeit of the lunar variety. When the Moon clears the oak trees at the end of my road, I feel a jolt of awe and purpose, of protectiveness and responsibility.

So if you need me tonight, that’s where I’ll be—staring up at the supermoon while folding an origami crane on my windowsill.

I doubt I have the temperament necessary to fold 1,000 pieces of paper. And even if I do manage the feat, a flock of paper birds will make this already cramped room even more claustrophobic.

But you never know.

Once pressed into shape, the cranes might take wing through the open window.

No one would believe me, of course.

But seeing those cranes fly off in the moonlight, skittering across the night sky on their amateurishly creased wings, well…that would be just as good as being healed.

See you on the Sturgeon Moon!

—WD

If you enjoyed this post, please subscribe to this monthly newsletter for free here:

Also, please consider sharing this post with some of your fellow Earthlings 🚀.

https://www.apa.org/monitor/2016/09/people-slack

https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/wanted-mars-explorers-must-be-able-to-tolerate-boredom-and-play-nice-with-others/

https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/station/research/news/b4h-3rd/hh-assessing-neurovestibular-system-health-in-space

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/activity-and-adventure/steve-smith-astronaut-interview/

https://commonplacefacts.com/2021/05/02/garn-scale-space-sickness/

Oh Will, I have Ménière’s Disease and I live with this disruption in gravity all the time. It was worse for about 18 months after my first bout of covid, but a little better now. You capture it so well.

You have my complete sympathy, having survived a couple of bouts of labyrinthitis. Thankfully my symptoms eased off after several weeks each time - I can’t imagine years of it!

Btw, parts of your essay made me queasy just reading about it - that’s a compliment to your writing, but not so pleasant for my head 🥴

That’s an excellent crane 🥰