Dear Lunatics,

This evening, as the Worm Moon wriggled over the horizon, my nephew simultaneously knocked on and opened my bedroom door (he’s four) and asked me to explain the number Pi to him.

Since I had yet to begin this Dispatch, I was inclined to tell him—very kindly—to beat it, but how often in life do you get the privilege of teaching Pi to a math-infatuated preschooler?

So forgive me, but I decided to split the worm in two: the kid got half my night, and now you’re getting the other half.

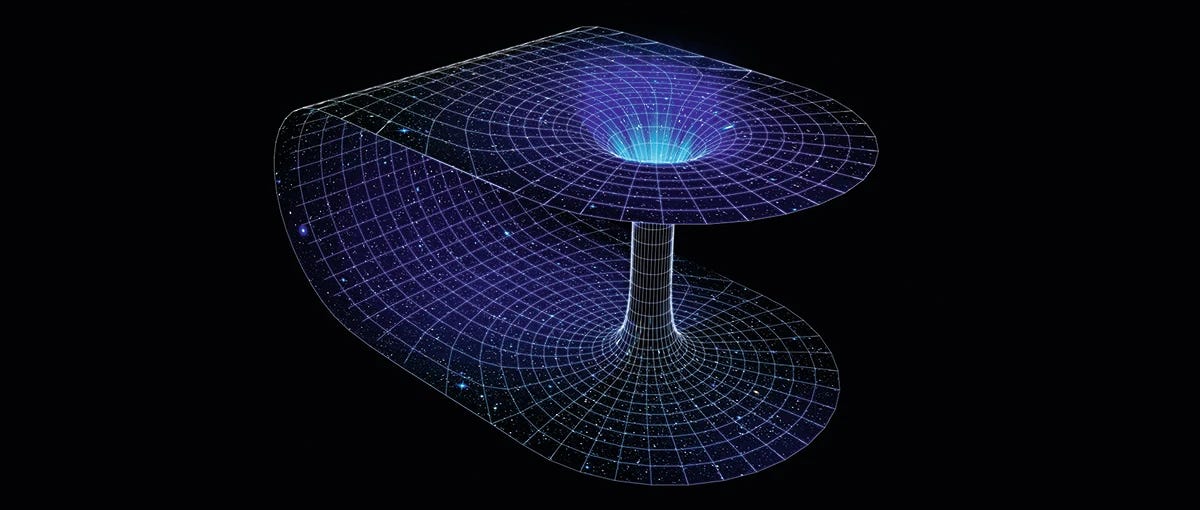

In an ideal universe, I’d slither back in time through a wormhole and redo the evening.

Unfortunately, in the century since Albert Einstein first proposed their existence, we’ve made very little progress in creating those theoretical spacetime tunnels.

All we've managed to do is simulate a wormhole on a quantum computer—well, we almost did.

I can’t be the only one dreaming wistfully of temporal culdesacs.

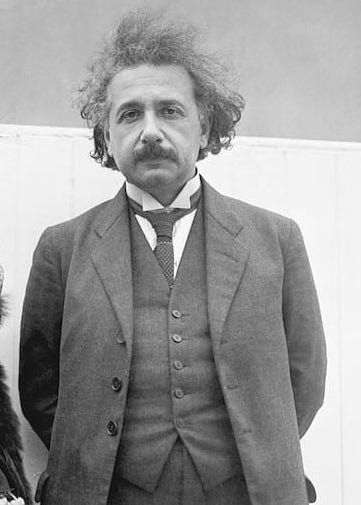

For the sake of his posthumous reputation, I bet Einstein wishes he could double back in time as well.

Let’s face it, the man had one hell of a century.

With his scientific and philanthropic bona fides beyond doubt, the only real question about Einstein was whether his mane of white hair was so frizzy because he’d managed to plug directly into an electrical socket of cosmic wisdom or because, like some saint living in the rugged wilderness of his own vast brilliance, he’d grown an untamable, iridescent halo.

His image was everywhere

The wise pipe-smoking grandfather with the childish wagging tongue mugged on billboards across the world, selling anything vaguely technological.

For decades, posters of Einstein have been such a feature on dorm room walls that they are practically load-bearing.

But a few months ago, Einstein suffered what might be called a professional setback.

"Scientists Win Physics Nobel Prize For Proving Einstein Wrong," the headlines trumpeted as three physicists—Alain Aspect, John Clauser, and Anton Zeilinger—were recognized for their experiments establishing the reality of quantum entanglement.

Einstein had always refused to accept entanglement and the zanier implications of quantum mechanics.

During an evening walk home from Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Studies, he famously pointed at the Moon and asked one of his quantumly-inclined colleagues, “Do you really believe the moon is not there when you are not looking at it?”

Honestly, I feel for Einstein.

Because I just glanced out my window twice in quick succession, and as far as I can tell, the Moon didn’t move a muscle.

But this isn’t the only blow to Einstein’s good name.

Recently, it’s been revealed that Einstein, much like the Moon, has a dark side.

Between October 1922 and March 1923, while lecturing across Europe and Asia, the world-famous physicist scribbled a handwritten diary not meant for publication.

Now, Princeton University Press has published a translation of these private travel notes.

It’s nice to know exactly what Einstein was doing and thinking exactly one hundred years ago today.

On March 7, 1923, Einstein was swanning around Madrid.

At noon, he met King Alfonso XIII of Spain, whom he admired for his “simple and dignified” manner; then in the evening, he delivered a lecture to a packed audience whom he claimed didn’t understand his cutting-edge ideas (it probably didn’t help that Einstein didn’t speak una palabra of Spanish); and finally, he attended a party at the German ambassador’s that was full of “magnificent, modest people,” though he later confided to his diary that he found making conversation “as punishing as always.”

Aside from his discovery of E=MC^2—that sleek little key of a formula that nearly unlocked the universe’s mysteries—Einstein is best known for his humanitarianism.

When he arrived in America after fleeing the Nazis, he decried segregation—“a disease of white people,” as he called it—and lent his fame and influence to anti-racist causes, joining the NAACP and co-chairing the ACAL (the American Crusade Against Lynching).

Yet thumbing through Einstein’s travel diary, I was startled to discover a glaring streak of racism: in his intimate scrawls, he refers to the Chinese as "obtuse" and "herd-like,” the Sri Lankans as “primitive,” and the Levantines as “spewed from hell.”

Even the historian and translator of the diaries, Ze’ev Rosenkranz, struggled to reconcile Einstein’s seemingly irreconcilable public and private selves.

As Rosenkranz told CNN, he hopes the diaries will prompt readers to consider their own contradictions and biases.

“We need to not just be judgmental about Einstein but to have an honest look at ourselves as well.”

Thanks to quantum computers, whose bizarre inner workings rely on the physics that so disturbed Einstein, we will soon have all of our dark sides revealed.

They call it Y2Q.

It’s the day, probably arriving in the next decade, when a fully-operational quantum computer will come online and render our current encryption methods instantly obsolete.

(A quantum computer will be able to crack a cryptographic key that would take a normal computer many millions of years to decode.)

Every email, every text message, every private social media communique you’ve ever sent will likely be swept up and deposited somewhere on the net, made accessible to friends, family, coworkers, and future biographers.

Welcome to the social apocalypse.

In minutes, the fragile grid of our common human relations will go down.

I don’t anticipate violent anarchy in the streets.

Instead, I think there will be a long period of raw emotional fallout during which most of us will hide in our bedrooms, wishing we could go back in time and un-send all those petty and cruel jottings, until finally, our hair will become as shaggy and unkempt as Einstein’s, and we’ll have to grit our teeth and return to our barbers.

Our barbers will know how much we hated the last cut they gave us, and we will know how insulting they found our tip. But locked in an excruciating stalemate of mutually assured destruction, we won’t talk about it. We won’t acknowledge what we now know—that the other is utterly two-faced. Instead, we’ll grin at each other in the mirror and make painful conversation.

So what will we do with a figure like Einstein, who used his public voice to rail against bigotry in all its forms while giving vent to unsavory prejudice in his private notes?

And what will we do with each other, when we learn that our closest, most trusted confidants are as dual-natured as any quantum entity?

Most importantly, what will we do with ourselves, when we’re forced to confront the fact that our appalling shadow selves do in fact exist, even when we’re not looking at them?

When the interpersonal world goes quantum, we will need grace.

We will need to consider that the small-minded, nasty things we write behind each other’s backs may not be what we really think, but rather the refuse we consciously discard so that we can show our true faces to the world.

As Einstein wrote to a girl who was struggling with the death of her younger sister:

A human being is a part of the whole called by us universe, a part limited in time and space. He experiences himself, his thoughts and feeling as something separated from the rest, a kind of optical delusion of his consciousness. This delusion is a kind of prison for us, restricting us to our personal desires and to affection for a few persons nearest to us. Our task must be to free ourselves from this prison by widening our circle of compassion to embrace all living creatures and the whole of nature in its beauty.

It’s too late to prevent Y2Q.

We’ve already constructed our prisons out of screenshots and eye-rolling emojis; now it’s just a matter of time before the steel bars descend, separating us each into our own cells.

There will be only one hope for escape.

One sleek little key that can free us all.

Mutually assured forgiveness.

I’m sorry this newsletter was shorter—and later—than usual.

Will you forgive me?

See you on the Pink Moon!

—WD

If you enjoyed this post, please subscribe to this monthly newsletter for free here:

Also, please consider sharing this post with some of your fellow Earthlings 🚀.

Loved this one. Grace and forgiveness - hopefully that is what people will choose.

That is my favorite quote of Einstein’s, and I believe it touches on what is highly important for all human beings - to be inclusive, compassionate and acknowledge we are all in this together.

I have wanted so much to be perceived as a good person that it can scare me to think someone else might think I’ve done something bad or wrong. But unfortunately, or fortunately maybe, all humans are flawed, it isn’t possible to be absolutely without fault.

I’m not judging Einstein too harshly for his private thoughts. I think his actions are ultimately what matters. As a traveler I think it can be expected that upon seeing new cultures you might have an initial negative reaction, but I don’t imagine he was behaving in a way towards those people that was harmful to them. But i also have no idea.

Maybe with that quantum computer, people will realize that we can stop pointing the finger at others and accept that we are all a work in progress. And maybe people will start being more honest about their true feelings and will be liberated. What I want most is for people to be real.

"With his scientific and philanthropic bona fides beyond doubt, the only real question about Einstein was whether his mane of white hair was so frizzy because he’d managed to plug directly into an electrical socket of cosmic wisdom or because, like some saint living in the rugged wilderness of his own vast brilliance, he’d grown an untamable, iridescent halo."

Brilliant!

"Mutually assured forgiveness", also a lovely turn of phrase. I approve, that sounds like a sure fire way to make it through.